Iran-U.S. Relations – Assessing the Future by Reviewing the Past

Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and Secretary of State John Kerry shake hands after signing an interim deal on Iran’s nuclear program, Geneva, November 24, 2013 (photo from theiranproject.com)

National Security Archive’s New Declassified Documents Publication Offers Historical Context for Current Crisis

As 2020 gets underway, tensions between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran have once again been dominating the headlines. A series of violent flareups – most recently the U.S. killing of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani and Iran’s retaliation against two Iraqi military bases housing American forces – have renewed fears of an escalation to direct armed conflict. The worry is that such a conflict will engulf the Middle East and create both global political instability, through increased terrorist attacks, and economic crisis in the event of a blockade of the Strait of Hormuz or strikes against oil facilities in the Persian Gulf.

A look back at the 40 years since the Iranian revolution of 1978-1979 – made possible by a new major documentary publication by the National Security Archive – offers some useful historical context that helps to explain the depths of American-Iranian official antagonism but also may provide some hope for extricating the two sides from what is in many ways just the latest confrontation between the two governments.

The Archive’s new publication, U.S. Policy toward Iran: From the Revolution to the Nuclear Accord, 1978-2015, is the most recent in the subscription series The Digital National Security Archive, published by the academic publisher ProQuest. It consists of 1,760 documents and almost 14,000 pages of materials, most of them made available through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) or through research at various archives.

A selection of highlights from the collection appeared in a recent Archive e-book that can be read here. They include Top Secret memos to presidents, assessments of the Iran-Iraq War and U.S. awareness of Iraq’s use of chemical weapons, records of U.S. and Iranian attempts to communicate including a direct message from Bill Clinton to Mohammad Khatami, Bush 43 records on Iran’s role in the Afghan Conference, queries from Donald Rumsfeld about Iran’s strategy in Iraq, and materials relating to negotiating the JCPOA.

What do the documents in this new collection, and the broad history of U.S.-Iran relations, show? The following are some examples based on the newly published materials.

Sultan Qaboos bin Said Al-Said of Oman, here in conversation with President George H.W. Bush, played a key role over many years as an intermediary between the United States and Iran. The Sultan died in January 2020.

On the surface the documentation forms a portrait of seemingly unrelieved hostility, beginning with the revolution itself, which exposed the depths of Iranian animosity not only toward Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, whose rein had followed a steady arc toward oppression and dictatorship as the years went on, but against the United States for its support of the Shah (starting with his restoration to the throne in 1953 thanks to a coup fomented with American and British help).

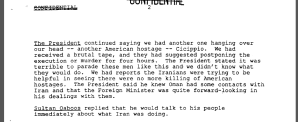

A period of tensions through most of 1979 turned ugly in November when Iranian students and others overran the U.S. Embassy and took dozens of American officials and military personnel hostage. That 444-day crisis has been at the heart of the American narrative about the Islamic Republic ever since and according to recent media reports was one of the motivations for President Donald Trump’s decision to respond sharply to demonstrations in front of the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad in late December 2019, out of fear it could lead to a similar crisis.

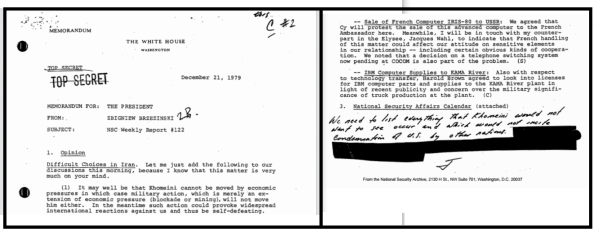

Portions of Zbigniew Brzezinski’s December 21, 1979 memo to President Carter, including Carter’s handwritten notes.

In hopes of ending the earlier drama, President Jimmy Carter mounted a rescue attempt in April 1980 that instead culminated in fiery disaster when two American aircraft collided in the Iranian desert before the operation could fully get underway. Ever since, that failure has loomed over the thinking of military strategists who have been tasked by different presidents with coming up with options for military operations against Iran. In addition to the stark logistical challenges, presidential aides have typically pointed to the unknowns and risks in terms of Iranian retaliation in advising the White House to steer clear of the temptation to use brute force against Tehran. Like his predecessors, President Trump by most accounts – and against the expectations of numerous observers – seems to have accepted that line of argument over the past year as he has opted more than once not to strike directly at Iranian targets, at least for now.

For their part, Iran’s leaders have developed a narrative concerning U.S. bad behavior. That image, formed over the years prior to the revolution, hardened significantly in the 1980s when Tehran was at war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. As the documentary record shows, Iran took great umbrage at most of the world’s lack of outrage following Baghdad’s attack in September 1980, at Western and Russian supplies of military materiel to Iraq, and at the perceived lack of indignation at Saddam Hussein’s use of chemical weapons (with targeting assistance from the U.S.). For Washington, concerns about the threat Iran posed to Western interests significantly outweighed that presented by Iraq. This became the justification for repeatedly and progressively siding with Saddam Hussein, a pattern that has been forgotten or obscured by Iraq’s subsequent aggressions and U.S. military operations against Baghdad in the early 1990s and starting in 2003.

Two sets of events from the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s resonate particularly strongly in today’s environment. The first started in Summer 1987 when the U.S. Navy began to escort Kuwaiti oil tankers through the Strait of Hormuz as a way to ensure the safe transit of petroleum to the West. That September, the U.S. discovered an Iranian ship laying mines in the Gulf, which led to a brief firefight and the destruction of an Iranian offshore oil platform. In April 1988, the U.S. determined Iran was at it again. This time the Navy responded by striking two more oil platforms which the Iranians were using as operational bases. Iranian small vessels retaliated against overwhelmingly larger American forces, which in turn responded by sinking several Iranian ships.

The mining incidents and missile strikes against international shipping in the Gulf and Saudi oil facilities in Spring and Fall 2019, which the U.S. charged Iran was responsible for, have recalled those earlier episodes, ramping up fears of a dangerous direct conflict.

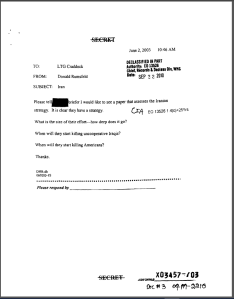

This “snowflake” memo from SecDef Donald Rumsfeld, written several weeks after George W. Bush declared “mission accomplished” in Iraq, anticipates the kinds of actions by Iran that would eventually be put forward as a key rationale for killing Qasem Soleimani.

The other event from the Iran-Iraq War with an almost eerie parallel to today was the July 1988 shooting down of a civilian Iranian airliner by the U.S. Navy cruiser USS Vincennes in the Gulf. The U.S. has always maintained it was an accident and subsequently gave the ship’s commander an end-of-tour award. The Islamic Republic immediately concluded the attack was deliberate and has held it out ever since as proof of American ruthlessness. When a Ukrainian civilian airliner went down over Iran in early January 2020, the regime was eventually forced to admit that its own missiles had shot the plane down. A substantial number of Iranian students were among the victims which prompted bitter protests in the country. In 1988, the Iran Air tragedy ironically helped persuade Tehran’s leadership that it was time to end the war with Iraq, in part because of the conclusion that they were also fighting the United States. It remains to be seen whether the latest calamity will also move the Islamic Republic to pull back in some way, perhaps through some combination of a sense of overwhelming odds and the ramifications of continuing public distress.

Throughout the four decades since the Iranian revolution, both the U.S. and Iran have routinely exchanged charges against each other. Washington has pointed to events such as the 1983 Marine barracks bombing in Beirut, kidnappings in Lebanon, the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia, violent attacks from Berlin to Buenos Aires, and general support for proxies including Hezbollah and Hamas as signs of Tehran’s bad intentions and support for international terror. The Islamic Republic in turn accuses Washington of pursuing its own brand of terror including imposing hegemony on the region, fomenting regime change in Iran, and supporting actors hostile to Tehran, from Israel to the MEK.

Yet, as the documents show, the past 40 years have also featured regular attempts beneath the surface by both sides to break through the political permafrost when it has suited them. In the months after the Shah’s 1979 flight into exile and Ayatollah Khomeini’s return to Tehran, the Carter administration tried hard to build ties to the new centers of power in Iran, albeit unsuccessfully. During the ensuing hostage saga, Washington worked with many intermediaries to try to resolve the crisis. Just a few years later, facing his own hostage predicament, President Ronald Reagan approved the covert trade of arms for Americans being held by Hezbollah in Lebanon. Observers dismissed the Iran-Contra affair as an aberration but underlying it was a much broader sense (as revealed in internal U.S. files) within the U.S. government of the desirability of finding a way to restore closer ties with Iran, despite the mutual hostility. Reagan’s successor, President George H.W. Bush, also tried to work with Tehran.

A new phase of the relationship (if it can be called that) opened with the election of Mohammad Khatami as president of Iran in 1997. President Bill Clinton tried repeatedly for a breakthrough, but a combination of domestic and international political factors hampered both sides’ attempts. Iran’s interest in improving relations showed through once again in the period after 9/11 when Tehran was one of the first world capitals to express public condolences to the United States. More substantively, Iranian and American negotiators in Afghanistan worked cooperatively as part of the international process of putting together a new Afghan constitution. Those positive steps were nullified at least temporarily by President George W. Bush’s branding of Iran as part of an “Axis of Evil” in January 2002. Still, American and Iranian officials found common ground in both Iraq and Afghanistan as they attempted to establish regional stability and eradicate Sunni-based terrorism. Recent accounts by then-Ambassador Ryan Crocker and others indicate that Qasem Soleimani himself was at times a willing partner in that process.

The most high-profile bilateral attempt to reach accord on matters of major mutual interest occurred during the presidencies of Barack Obama and Hassan Rouhani. The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action focusing on Iran’s nuclear program had many critics but was a landmark agreement that showed what could be achieved even by two such unfriendly parties. As so often happened over the course of the relationship, a combination of events on the ground, domestic political considerations, and other factors got in the way of a more permanent accomplishment.

Yet even Donald Trump, despite his harsh rhetoric and actions such as tearing up the JCPOA and imposing extensive sanctions, has stated openly he would be willing sit down and talk with his Iranian counterparts – without preconditions. Public statements by some of his advisers, notably Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s May 2018 enumeration of a dozen demands for “major changes” by Iran, directly contradict the president, but the evidence to date suggests that at least until the killing of Soleimani Trump has been far less enamored of taking the kinds of military steps his hardline advisers have been promoting.

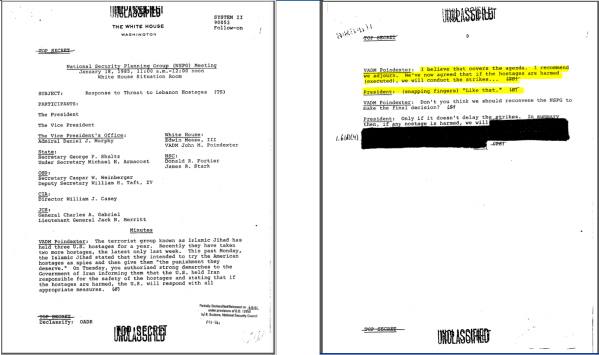

Even in the case of the Soleimani strike, Trump has followed a pattern set by his predecessors – establishing a red line at the killing of Americans. In early 1985, for example, Ronald Reagan – against the advice of his aides – insisted on hitting Iranian targets directly if any American hostages were killed. Bill Clinton ordered large-scale plans for attacking Iran if it could be proven Iran’s leaders was behind the Khobar Towers bombing that killed 18 American servicemen. (Clinton backed off after Khatami’s election because of the prospects for a rapprochement – one of many fascinating subplots outlined in the declassified record.) Where Trump has taken a different approach is in claiming credit for Soleimani’s death. In the past, the targeting of each other’s personnel or facilities has more typically been done behind the fig leaf of official deniability.

“Like that.” Preoccupied with American hostages in Lebanon, President Ronald Reagan was ready to strike Iranian targets directly if any harm were to come to the captives. This was several months before embarking on the widely criticized arms-for-hostages deals with Iran.

Where are events headed?

Based on a reading of the available record, it is clear that U.S.-Iran relations have been far more complex than they appear on the surface. Despite the trademark “Death to America” chants and similarly acrimonious rhetoric from various American administrations and Congress, each side at one point or another has found it in its interests to seek common ground with the other. Even when tensions have skyrocketed and war has seemed imminent, both governments have managed to pull back, sharing another common feature – a very rational desire not to become embroiled in a bloody direct conflict that could easily dwarf anything either side has experienced for many years.

On a less optimistic note, the record also shows that despite these intentions on the part of the leaders of both countries, a variety of factors continue to pose potentially serious hazards for the region. Among these are a substantial degree of ignorance about the other side (its history, culture, politics, and decision-making) and a dearth of avenues for direct contact. Both are a result of the absence of formal diplomatic ties, which the U.S. has found a way to justify with virtually all of even its most reviled adversaries in the past, but not with the Islamic Republic. Another factor is the impact of domestic politics and the sharpening of political divides, particularly in the United States. Time and again, hardliners in both countries’ security apparatus and parliaments, for example, have torpedoed efforts to work toward a lessening of tensions.

A third, somewhat related, dynamic that has come into play is the preoccupation with showing strength over weakness. The historical record includes several examples of this from Carter forward to Trump. One of the most notable was the submission of a “road map” for better relations by Iran in the wake of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, which the American side dismissed at least in part because it was seen as proof that Iran was now in a weakened position and did not present an obstacle to American plans. Other issues came into play including U.S. uncertainty over the authenticity of the document, sent via the Swiss ambassador (who remains the principal go-between with Iran in the current crisis), but the instance is one of several that raise fascinating questions about what might have been, especially in the light of how Iran’s position has strengthened by orders of magnitude since that time.

Finally, events on the ground make up a very concrete, additional source of continuing mutual antagonism, which may yet contribute, along with the other circumstances above, to an open explosion in the region. Mistrust based on all these factors has been a persistent feature in both governments for many years, but so have a certain underlying rationality and sense of self-interest, despite perceptions on both sides. The unpredictable interplay of these conflicting elements is a core reason why most Iran experts find it so difficult to foretell the future of the U.S.-Iran relationship.

Comments are closed.

Very nice analysis of Iran-US relations! Sadly, as the article notes, despite the good intentions of the leaders, there is less optimism in where this is all headed.

Thanks for this interesting exposé. It seems like Covid-19 has decreases war tensions a bit for the time being.