Washington, D.C., May 30, 2019 – The National Security Archive joins our international and Guatemalan colleagues in calling for the protection of the Historical Archive of the National Police (AHPN) of Guatemala, which faces new threats to its independence and to public access to its holdings.

In a press conference on Monday, May 27, Interior Minister Enrique Degenhart signaled his intent to assert his agency’s control of the AHPN including the prospect of new restrictions on access to the archived police records and possible legal action against “foreign institutions” holding digitized copies of the documents. Degenhart made his statements as a crucial deadline approached to renew an agreement that for a decade has kept the archive under the authority of the Ministry of Culture and Sports. The agreement now appears to be in jeopardy.

The hollowing out of the AHPN is taking place at a time when justice and human rights initiatives are broadly under siege in Guatemala and follows months of uncertainty for the celebrated human rights archive, which has been institutionally adrift since its long-time director, Gustavo Meoño Brenner, was abruptly dismissed in August 2018.

Since its discovery in 2005, the AHPN has played a central role in Guatemala’s attempts to reckon with its bloody past. Its records of more than a century of the history of the former National Police have been relied upon by families of the disappeared, scholars, and prosecutors. The institution has become a model across Latin America and around the world for the rescue and preservation of vital historical records.

* * * * *

Historical Background and Current Threat to the AHPN

by Kate Doyle

In a press conference Monday, May 27, Interior Minister of Guatemala Enrique Degenhart signaled his intent to assert his agency’s control of the country’s Historical Archive of the National Police (AHPN). He claimed that existing law required new restrictions on access to the archived police records and warned “foreign institutions” holding digitized copies of the documents that the government was considering legal action against them. Degenhart made his statements as a crucial deadline approached to renew an agreement that for a decade has kept the archive under the authority of the Ministry of Culture and Sports. The agreement now appears to be in jeopardy.

The comments follow months of uncertainty for the celebrated human rights archive, which has been institutionally adrift since its long-time director, Gustavo Meoño Brenner, was abruptly dismissed in August 2018. In the wake of Meoño’s departure, the Culture Ministry and the Guatemalan office of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) – responsible for administering international donations to the AHPN – instituted drastic cuts to the archive’s budget and personnel. The two agencies agreed to eliminate the position of director in favor of a “technical liaison” and hired a trained archivist with no human rights experience to fill it. They dismissed all but one member of the investigative staff dedicated to locating and analyzing police records containing information about illegal State terror campaigns during the 1970s and 80s.

The hollowing out of the Historical Archive of the National Police is taking place at a time when justice and human rights initiatives are broadly under siege in Guatemala. The attacks come from every branch of government. In January 2019, President Jimmy Morales ordered the closing of CICIG, the UN-sponsored commission that for over a decade helped prosecute cases of corruption and organized crime. Congress has offered several versions of an amnesty bill aimed at releasing from prison scores of former Army, police, and paramilitary members found guilty of grave human rights crimes and crimes against humanity. Although none of the bills has passed yet, they hang like Damocles’ sword over victims of human rights crimes and their families. And in March a judge issued an arrest warrant for former Attorney General Thelma Aldana – known during her term in office for major anti-corruption and human rights prosecutions – accusing her of embezzlement and other crimes. Aldana has categorically denied the charges but the move quashed her hopes to compete as a candidate in the upcoming presidential elections scheduled for June 16.

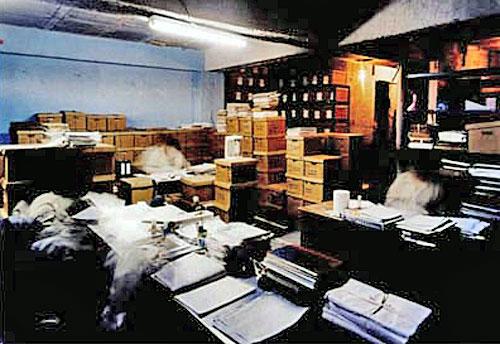

Since its discovery in 2005, the Historical Archive of the National Police has played a key role in Guatemala’s attempts to reckon with its bloody past. It holds the files of more than a century of the institutional history of the former National Police, including millions of pages that chronicle the State’s repressive policies against Guatemalan citizens during the 36-year armed internal conflict (1960-96). Its records have been used by families of the disappeared to research the fate of their loved ones, scholars have drawn on the collection to examine the history of guerrilla warfare and brutal counterinsurgency policies, and prosecutors have incorporated records as evidence into some of the most important criminal human rights cases tried by Guatemalan courts.

The AHPN also offers a wealth of documentation on the country’s social history, the history of public order, and the role of the police. Over the years, it has become a model across Latin America and around the world for the extraordinary achievement of its staff and management in rescuing the enormous, abandoned collection, and for its professional work since then in preserving the records, guaranteeing public access, and undertaking research of vital, contemporary relevance.

But for all its achievements, the Police Archive has existed in a precarious legal and fiscal status since its discovery almost 14 years ago. As a repository for the historical records of a former government security force, it functioned by definition under the authority of the State; yet except for the office of the Human Rights Prosecutor (Procuradoría de Derechos Humanos—PDH) – which found the neglected archive in 2005 and managed it until 2009 – the State never took leadership in overseeing the AHPN nor any financial responsibility for its operations. Instead, funding for the archive came from foreign governments – including millions of dollars from the United States – and international organizations, and flowed primarily through the UNDP. That funding dropped precipitously in recent years, as the attention of many governments drifted on to other countries and other priorities.

More complicated still, when the archive was discovered, the State entity with direct authority over it was the Interior Ministry, which controls the country’s security forces, their properties and their records. Recognizing the potential danger of that position, the PDH and the AHPN – under former director Meoño – worked with the government of then-President Álvaro Colom to negotiate the archive’s transfer from the Interior Ministry to the Ministry of Culture and Sports, already the institutional home for the country’s General Archives of Central America (national archives). The transfer was effected by way of a signed agreement in 2009, conveying to Culture the physical records and the land on which the AHPN sat, a small territory inside a huge police base in Zone 6 of Guatemala City. The agreement terminates on June 30 of this year and must be renegotiated and re-signed to continue.

Even with the agreement in force, the problem remained that the AHPN as an institution was never formally accredited through any instrument under Guatemalan law, rendering it permanently vulnerable. Now the government is moving in on that vulnerability. Current Interior Minister Enrique Degenhart is one of Jimmy Morales’s closest advisers. He has aided the president’s campaign to shutter CICIG and aggressively backed efforts to arrest former Attorney General Aldana. His remarks on Monday concerning the Police Archive are the strongest indication yet that the government intends to intervene forcefully in AHPN operations and functions.

Degenhart referred to the collection as the “Historical Archive of the National Civil Police” – incorrectly imposing the name of the security force he heads for the National Police, which was abolished in 1997 by the peace accords for its role in assassinating, disappearing and torturing Guatemalan citizens during the conflict. He bristled at questions from journalists about his authority over the AHPN, saying, “The fact that the Interior Ministry through the National Civil Police does not participate in the management of its own archives is totally inconceivable.”

Degenhart repeatedly invoked Guatemala’s access to information law during his remarks (Ley de Acceso a la Información Pública, the Guatemalan version of the Freedom of Information Act) – not to promote open access to the police records but rather to insist that the records of the AHPN contain “restricted information” defined by the law and must be “protected” (in other words, withheld). Included in his concept of information restricted under the law was the “identification of persons,” which merited “special treatment.” Degenhart made no reference to Article 24 of the access to information law, which states that “In no instance can information related to the investigation of the violation of fundamental human rights or crimes against humanity be classified as confidential or reserved.”

The Interior Minister also made a point of lambasting the AHPN’s decision to provide the Swiss government and the University of Texas at Austin with complete digitized copies of the police records. Former director Meoño and other senior staff made the move years ago both to ensure that a back-up copy existed in the event of an attack on the archive and to make access to the collection possible from outside Guatemala. Although Degenhart was vague about the Police Archive’s immediate future, he was abundantly clear about the government’s intention to alter the sharing arrangements.

“What I can tell you for sure is that we will not permit the massive exit of those archives outside the country,” he stated. When a journalist asked why, he answered: “Because it is sensitive information concerning national security, protected by the Law on Access to Public Information. There cannot be foreign institutions that hold a complete set of the archives.” He warned that the government was preparing legal action to challenge the agreements.

The AHPN is not the only archive serving human rights purposes under attack in Guatemala. Guatemalan media outlets reported in late March that both the chief of the General Archive of the Supreme Court – Rossana Aracely Alvarado Cortez – and the head of the Court’s Information System – Daniel Girón – were pressured to resign by Justice Department (Organismo Judicial) officials. Among the documents under Alvarado’s care were records gathered by Guatemalan tribunals in preparing cases for trial, including expert reports, witness statements and evidentiary material. Since the tribunals include the special, “high risk” courts that take on corruption and human rights cases, the lack of a director could make the archive vulnerable to interference.

A senior employee of the Justice Department reached for comment on the forced resignations called them “the destruction of justice” and a direct attack on the institution.

Another archive under stress is the collection of records of the former “Presidential General Staff” (Estado Mayor Presidencial—EMP), located inside the General Archive of Central America, Guatemala’s national archives. During the armed conflict, the EMP was a military intelligence unit serving the Chief of State, which became a notorious instrument of repression and violence. Some of its files were rescued and copied by human rights groups after President Alfonso Portillo dissolved the EMP in 2003, and the collection moved to the national archives in 2012. According to a recent column in El Periódico, the staff managing the EMP files was laid off in March. “As a result,” wrote author Manolo Vela Castañeda, “beginning in April, the cataloguing work has stopped and there is no one to attend to information requests…”

In response to the government’s actions, a broad collective of AHPN supporters have come forward to defend the Police Archive. Following Meoño’s dismissal in 2018, a civil society advisory group of Guatemalan human rights leaders, scholars, lawyers, and justice reform experts mobilized and have been a constant presence in discussions about the archive’s future. Hundreds of international allies of the AHPN – including historians, human rights groups, and archivists from around the world – signed a letter calling for the archive’s protection last summer. The National Security Archive sent this analyst for two weeks of meetings and talks with key stakeholders last October. And the widely respected Spanish archivist, Dr. Antonio González Quintana, wrote a comprehensive report on the Police Archive that assesses its current status and outlines a detailed strategy to strengthen the AHPN in the future. The report was delivered to the UNDP in February.

More recently, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights, Archives Without Borders, the Guatemalan Association of Friends of UNESCO, and the Myrna Mack Foundation among many other organizations have issued statements protesting the government’s interference in the AHPN. On May 16, Human Rights Prosecutor Jordan Rodas Andrade submitted a legal complaint to the courts against the Ministries of Culture and Interior to force them to renew the agreement guaranteeing a continuation of its occupation of the police base in Zone 6 and the preservation of its documents.

The National Security Archive joins our international and Guatemalan colleagues in calling for the protection of the Historical Archive of the National Police of Guatemala. Specifically, the National Security Archive demands with our colleagues:

- Protection of the archive’s irreplaceable trove of records from physical damage and political interference

- Preservation of secure, digitized copies with the Swiss government and University of Texas at Austin

- Renewal of the lease that permits the archive to remain in its original space

- Improvement in the information system that hosts the 23 million document images scanned to date

- Guarantees of the public’s ability to consult the records without restriction through its Access to Information Unit

- And continuation of the archive’s support for human rights justice through investigations and analysis.