Related LinksMigration Declassified "Mexican Authorities Implicated in Violence, but U.S. Security Aid Continues to Flow" "Suspende EU apoyo a batallón del Ejército implicado en el caso Tlatlaya: “The Intercept”" "After Long Fight, Groups Pry Memo on Migrant Killings From Mexican Government" "San Fernando-Ayotzinapa: las similitudes" "Unearthing the Truth: Mexican State Violence Beyond Ayotzinapa" "New Document Throws More Light on Mexico’s San Fernando Killings" "PGR entrega datos sobre participación de policías de San Fernando en masacre de migrantes" "A la luz, los secretos de las matanzas de Tamaulipas" "Mexico's San Fernando Massacres: A Declassified History" "On International Right to Know Day, a Call to Declassify Migrant Massacres in Mexico" "Mexican Prosecutor’s Office Ordered to Release Records on San Fernando Massacre" "Four Years Later, Mexican Migration Agency Makes First Disclosure on 2010 San Fernando Massacre" "Mexican Court Orders Release of Documents on Massacre Investigations" "Three Years Later, Still No Justice for 2011 San Fernando Killings" "Mexican court orders a new review of the San Fernando massacre" "Migrant Massacre Focus of Legal Effort against Mexico’s Human Rights Commission" "Near total impunity" for Mexican Cartels “in the face of compromised local security forces,” U.S. Cable "Secrets of the Tamaulipas Massacres Come to Light in Proceso Magazine" "IFAI denies access to information on the case of the San Fernando Massacre" "Mexican Officials Downplayed 'State’s Responsibility' for Migrant Massacres" "Article 19 launches Right to Truth campaign for access to official records on the San Fernando Massacre"

|

Washington, DC, May 12, 2015 – A U.S. military “Human Rights Working Group” said that mass graves not related to the September 2014 disappearance of 43 students in Guerrero, Mexico—but nevertheless found during the investigation of that case—raised “alarming questions” about the “level of government complicity” in Mexican cartel killings. The student victims from a rural teachers college in Ayotzinapa were allegedly abducted by local police forces and turned over to members of a local drug gang to be executed. All but one of the students—whose remains were reportedly identified by an Austrian forensic group—are still missing seven months later. The October 2014 report from U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) is one of several declassified records obtained by the nongovernmental National Security Archive and highlighted in a new report for The Intercept by former Archive staffer Jesse Franzblau and Cora Currier. The newly-declassified records, some posted here for the first time, shed light on how the U.S. has perceived and responded to allegations of serious human rights abuses committed by U.S.-funded security forces in Mexico, which have become disturbingly common in recent years. “None of the 28 bodies identified thus far are the remains of the students,” reads a summary of the Working Group meeting circulated to senior officers at NORTHCOM on October 14, 2014, “raising alarming questions about the widespread nature of cartel violence in the region and the level of government complicity.” NORTHCOM, based in Colorado, is the regional military command in charge of Defense Department programs in the United States, Canada and Mexico. Another item on the Working Group’s agenda was the June 2014 slaying of 22 suspected drug gang members at Tlatlaya, in the state of Mexico, by the Mexican Army’s 102nd Battalion. Four months later, and shortly after the arrests of a Mexican Army officer and seven soldiers from the 102nd for the killings and subsequent cover up, the Working Group “assesse[d] that as more facts come to light there is greater acceptance that the military was involved in wrongdoing,” raising serious questions about the ability of the U.S. to provide aid to military forces in the region. “If [the military zone commander is] implicated in a gross human rights violation,” the Working Group reported, “the entire military zone and 10,000 personnel will be ineligible for U.S. security cooperation assistance.” Another NORTHCOM document obtained by the Archive and highlighted in the report is the first public confirmation that the U.S. State Department last year did quietly suspend assistance to the 102nd Battalion following Tlatlaya, pending the outcome of official investigations. The NORTHCOM “Information Paper on San Pedro Limon, Tlatlaya Incident” indicates that the 102nd “is now ineligible to receive US assistance.” Questioned about the reported suspension of aid by The Intercept, the State Department would only confirm that five members of the battalion had previously been trained by the U.S. but said that none of those five are implicated in the Tlatlaya case. A 1997 law introduced by Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) bars U.S. support to foreign security forces credibly linked to human rights violations. Franzblau and Currier call the suspension of aid in the Tlatlaya case “a rare confirmed example of the U.S. government actually cutting off funding for security forces” in Mexico. Even so, the State Department has not said whether any Mexican units tied to the Guerrero disappearances have been declared ineligible for U.S. aid, as the Leahy law would seem to require in this case. According to the authors, “The State Department’s piecemeal response to these events highlights the conundrum that Mexico now presents for the United States, as it seeks to help the Mexican government battle drug cartels.” The U.S. has provided some $3 billion in security assistance to Mexican forces since 2008, in addition to billions more in direct military sales and other aid. Franzblau and Currier cite a diplomatic cable published by Wikileaks to “show how U.S.-Mexico security and intelligence relations have reached unparalleled levels of intimacy” in recent years. The 2010 cable from the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City stresses that U.S. “ties with the Military” at that time had “never been closer in terms of not only equipment transfers and training” but also “intelligence exchanges.” But the unprecedented level of U.S. influence on Mexico’s armed forces came alongside an extraordinary increase in drug war abuses and in human rights violations connected to state and local security forces. The violence that has engulfed Mexico since then has produced a flurry of reports from U.S. diplomatic and intelligence officers expressing concern that America's drug war partners in the Mexican security forces were working hand-in-glove with cartel terrorists.

One of the key objectives of U.S. aid to Mexico during this time has been to beef up the country’s security communications infrastructure by lending funds, expertise and equipment to the Plataforma Mexico project, which the U.S. State Department described in 2007 as a “billion-dollar scheme for establishing interconnections between all police and prosecutors.” The U.S. poured millions of dollars into Plataforma Mexico, which was essentially a criminal database that connected state- and regional-level intelligence coordination centers known as “C-4s” (“command, control, communications and coordiation”) to each other and to law enforcement officials through a centralized, U.S.-funded command and control facility known as “The Bunker.” Franzblau and Currier point out that the “more sophisticated C-4s in Mexico’s northern region communicate directly with U.S. agencies, such as Department of Homeland Security offices across the border,” but there is good reason to question the overall effectiveness of the C-4s in combatting drug violence. A 2009 assessment said that neither Plataforma México nor the C-4 in San Pedro, in a suburban section of Monterrey, had been successful in hindering cartel operations. A declassified January 2010 cable from the U.S. Embassy in Mexico, for example, said that the C-4 facility in Tijuana was little more than a “glorified call center” for everyday emergencies that lacked “a strong analytical component.” Two months prior, a separate cable from the Embassy described a range of competency at the various C-4s, from, “at the low end, glorified emergency call centers,” to “[a]t the high end... more professional analytic cells that produce useful analysis and planning documents and also have a quick response time.”

Most importantly, as Franzblau and Currier note in their piece, the U.S.-funded C-4s also appear to have played a role in the disappearance of the 43 students in Guerrero:

Reports in the Mexican magazine Proceso and elsewhere linking regional C-4s and other government entities to the events surrounding the Ayotzinapa case have led many to question what the government knew about the massacre and have galvanized calls in Mexico for greater openness about government efforts to bring cartel thugs and their collaborators in the security forces to justice. It remains unclear whether the U.S. will apply Leahy Law sanctions to the C-4 units that were apprently involved in the disappearance of the 43 students. Mexican authorities have promised transparency but have largely resisted the efforts of journalists and academics to gain access to records on the cases. This despite the fact that Mexican law requires the release of information pertaining to grave violations of human rights in all cases. (In one notable exception, Mexico’s attorney general last year declassified a document from its case file on the 2011 San Fernando massacre showing that local police helped to round up hundreds of migrants later killed at the hands of the Zetas cartel.) Mexican government stonewalling about the case has some looking to the U.S.—Mexico’s chief sponsor and partner in the anti-drug effort—for answers. A key part of the U.S. paper trail are records indicating how the U.S. government determines whether to suspend security assistance to members and units of the Mexican security forces involved in human rights abuses. One newly-declassified document shows that senior U.S. military officials from NORTHCOM reached out to counterparts from Mexico’s Defense Ministry (SEDENA) about the Tlatlaya killings after receiving multiple questions about the case. “Since we’ve continued to get inquiries as to what we’ve specifically talked to SEDENA about ref. the Tlatlaya incident, I made a call to SEDENA Enlace,” reads an October 2014 message from the Pentagon official in charge of U.S. military assistance programs in Mexico (the Office of Defense Cooperation – ODC). Among other things, the ODC chief said it was “good news” to hear from SEDENA that alleged human rights cases like Tlatlaya are “taken out of the military justice system” and transferred to civilian authorities. A 2014 law requires Mexico’s attorney general to prosecute all cases in which Mexican security forces are accused of abusing civilians. But as Franzblau and Currier point out, it is not at all clear that the civil justice system has been any more effective at punishing human rights violators than military tribunals:

There are no easy answers to the “alarming questions” raised by the shocking number of mass graves now being unearthed in Mexico. What seems clear is that a U.S. strategy that has poured billions of dollars into Mexico’s drug war over the last decade—mostly aimed at taking down high-profile cartel kingpins—has done little to stem epidemic levels of violence or limit the criminal groups’ ability to compromise government officials at all levels. For more on this topic, check out Franzblau and Currier’s new article over at The Intercept.

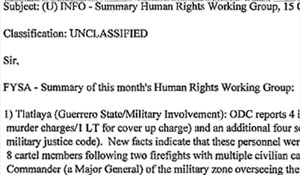

THE DOCUMENTS Document 1 In a briefing paper prepared for U.S. Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte's meeting with the head of Mexico's Public Security Secretariat (SSP), the State Department's bureau for the Western Hemisphere says SSP chief Genaro Garcia Luna is "creating a massive system of interconnectivity between all levels of law enforcement, Plataforma Mexico, a billion dollar project." Negroponte is instructed to ask, if time allows, about "how Mexican jurisprudence treats privacy issues in context of criminal databases." Source: FOIA Document 2 In a meeting with SSP director Garcia Luna, Deputy Secretary of State Negroponte "emphasized the need for good coordiation among police elements, and noted [the U.S.] commitment to helping Mexico meet its current security challenges." Garcia Luna told Negroponte about Plataforma Mexico, described in the meeting read-out as "the billion-dollar scheme for establishing interconnections between all police and prosecutors." The Plataforma "already reaches every Mexican state," according to the meeting record, "and by January [2008] would extend down to the municipalities, eventually reaching 2000." Source: U.S. Department of State, FOIA Appeals Review Panel Document 3 The U.S. Consulate in Monterrey, the capital of the Mexican state of Nuevo León, provides an assessment of law enforcement activities in the wealthy Monterrey suburb of San Pedro. The cable notes that Plataforma México has been installed in the San Pedro regional command, control, communication and coordination center (C-4) and that the U.S.-based global aerospace and technology company Northrop-Grumman served as a prime contractor for a similar facility in the state of Nuevo León, called the C-5. According to the assessment, U.S. consulate officials do not believe that either Plataforma México or the C-4 in San Pedro had been successful in hindering cartel operations. Source: Wikileaks Document 4 This cable provides a detailed assessment of the capacity of Mexico’s intelligence agencies, and explains the functions of the state level command and control centers, and the Plataforma database. The cable reads:

Source: Wikileaks Document 5 Like the previous document, this declassified cable from the U.S. Embassy in Mexico characterizes the C-4 center in Tijuana, Baja California, as a “glorified call center.” Source: FOIA Document 6 Source: Wikileaks Document 7 The U.S. Embassy's Narcotics Affairs Section provides a monthly summary of internal developments in Mexico, reporting that "March ended as one of the bloodiest months on record, with an estimated 900 killings nationwide." The cable says that Mexican government officials did not anticipate the sharp increase in violence in the northeast that occurred as the Zetas took control the lucrative plazas in the region. U.S. officials report the violence has "cut a swath across north-east Mexico, including key towns in Tamaulipas, Coahuila, and Nuevo Leon, and even in neighboring Durango." The Embassy message notes the failure of the Mexican authorities to manage the growing threat, highlighting how "DTO's [Drug Trafficking Organizations] have operated fairly openly and with freedom of movement and operations…In many cases they operated with near total impunity in the face of compromised local security forces." As part of U.S. support provided through the Mérida Initiative, the document also reports on U.S. efforts to implement an initiative to train regional police under the Culture of Lawfulness education initiative, involving officials from the now-defunct Secretariat of Public Security (SSP) in Baja California, Chihuahua, Nuevo Leon, Coahuila, and Tamaulipas. Source: FOIA Document 8 In August 2010, the State Department reported that over $6 million was authorized for the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) to support the implementation of the Plataforma software in regional C-4s. Source: FOIA Document 9 This document discusses how the DOD Counter Narcoterrorism Technology Program Office (CNTPO) contracted out projects to provide support for Mexico’s regional command centers (C-4s). The CNTPO request for proposals discusses requirements for program and operations support for ten C-4 sites. The support included providing relay capability at existing Mexican communications facilities for connectivity to the C-4 sites. This involved conducting site surveys in order to verify equipment required to satisfy the requirements for ten C-4 sites and two microwave relay facilities in Mexico that would correspond to microwave facilities run by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP). The contractor hired to provide the equipment was to interact with other Mexican and U.S. agencies (e.g. C-4s, DHS, CPB) where needed to perform and complete the required activities. The contractor was also tasked to provide training to personnel from Mexican state and federal offices. Source: FOIA Document 10 FBI authorities in Mexico report information connecting police officials in Saltillo, Coahuila, to the Zetas and to “drug trafficking and homicides.” A list of officers who “provided support and information to Los Zetas” is redacted from the document. Source: FOIA DOCUMENT 11 Summing up information taken from official sources, the U.S. Consulate reports that a total of 36 grave site containing 145 bodies were discovered in the San Fernando area during a SEDENA operation that took place April 1-14, 2011. Seventeen Zetas and 16 members of the San Fernando police have been arrested in connection with the deaths. The police officials are being charged with "protecting the Los Zetas TCO members responsible for the kidnapping and murder of bus passengers in the San Fernando area." Off the record, Mexican officials tell Consulate officials that "the bodies are being split up to make the total number less obvious and thus less alarming." Consulate officers also comment that, "Tamaulipas officials appear to be trying to downplay both the San Fernando discoveries and the state responsibility for them, even though a recent trip to Ciudad Victoria revealed state officials fully cognizant of the hazards of highway travel in this area." Source: FOIA Document 12 The chief of the U.S. Office of Defense Cooperation (ODC) in Mexico reports on his communications with Mexican defense officials after repeated queries about the Tlatlaya case. Source: FOIA Document 13 This summary of the U.S. Northern Command’s “Human Rights Working Group” from October 15, 2014 focuses on two major human rights cases of concern that month. The first case was related to the alleged military involvement in the Tlatlaya killings, in which four individuals had been taken into civilian custody (three soldiers for murder charges and one lieutenant for cover up charges) and an additional four soldiers were in military custody for violations of the military justice code. According to the report, “New facts indicate that these personnel were a patrol involved in the extrajudicial killing of 8 cartel members following two firefights with multiple civilian casualties.” The summary goes on to note that Mexico’s military is investigating the major general in charge of the military zone overseeing the battalion accused of the killing (the 102nd Battalion). The notes from the meeting indicate that if credible allegations connect the commander to a gross human rights violation, “the entire military zone and 10,000 personnel will be ineligible for U.S. security cooperation assistance.” Further, the U.S. Office of Defense Cooperation (ODC) assesses that as more facts come to light, “there is greater acceptance the military was involved in wrong-doing.” The other issue of concern for the U.S. military last October was the police involvement in the disappearance of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa kidnapped in Guerrero. While there had been approximately 50 arrests of police and government officials, the report notes that the students’ whereabouts are unknown. Further, nine new mass graves have been found outside of Iguala, but “None of the 28 bodies identified thus far are the remains of the students, raising alarming questions about the widespread nature of cartel violence in the region and the level of government complicity.” Source: FOIA Document 14 The document provides the latest update on the Tlatlaya killings, reporting that the government of Mexico “has detained and charged seven SEDENA personnel in conjunction with the killing of twenty-two individuals on 30 June 2014 in San Pedro Limon, Tlatlaya, Mexico State.” According to the report, “The unit implicated is now ineligible to receive US assistance.” The report states that none of the alleged perpetrators previously received U.S.-funded training, but notes that the incident has received “extensive negative coverage in international press and, along with subsequent cases involving police, has prompted non-government organizations to lobby the US legislature to suspend security assistance to Mexico.” The document gives the following account of the incident: “SEDENA members of the 120nd [sic] infantry Battalion stationed in Santa María Ixtapan responded to an anonymous call in the early morning of 30 June, regarding the presence of armed suspects at a warehouse in Tlatlaya. A firefight ensued between the military and the civilians on site (suspected to be members of the Guerreros Unidos Cartel). According to the Mexican Attorney General (PGR), one soldier was wounded during the confrontation, and all 22 of the civilians were either killed or wounded. Four soldiers are accused of entering the warehouse alter the conclusion of the firefight, and killing all remaining civilians. Evidence indicates up to fifteen of the twenty two civilians were killed alter the firefight, and prosecutions are focused on these killings.” The NORTHCOM information paper adds that “SEDENA’s 102nd Infantry Battalion, and that the State Department has suspended U.S. funded assistance to this unit pending the results of the investigations.” Source: FOIA |

|

US: Mexico Mass Graves Raise "Alarming Questions" about Government "Complicity" in September 2014 Cartel KillingsState Department Quietly Suspended Aid to Army Unit Responsible for June 2014 Tlatlaya Massacre

|