Annals of Overclassification

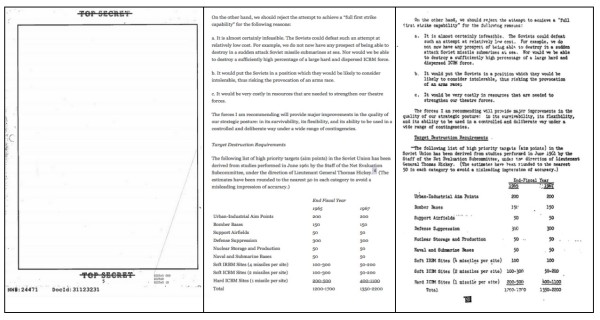

The same page – page 5 – from the same document, released 3 different times. From Left to Right: 2014 National Archives release with Department of Defense redactions, 1996 Foreign Relations of the United States release, and circa 1990 Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release. Image by Lauren Harper.

A recent National Archives response to a 2004 mandatory declassification review (MDR) request shows that much is wrong with the declassification process at the Pentagon. The MDR request was for file 471.6 (29 Aug 61), held in the records of former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. According to the old War Department decimal file system, as modified during the Cold War, 471.6 is a file about nuclear missile systems. After a ten-year wait for a response to the MDR request (itself a problem!), the file was reviewed by a variety of civilian and military organizations and finally opened up.

A review of the opened file at the National Archives in College Park showed that some of its contents were heavily excised despite their historic age…and previous declassification and publication. A long memorandum from McNamara to President Kennedy dated 23 September 1961 on “Recommended Long-Range Nuclear Delivery Forces, 1963-1967” was massively excised when the Office of Secretary of Defense and the Joint Staff redacted nearly 20 entire pages of text. Another document in the file was a memorandum from Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Lyman Lemnitzer to Secretary McNamara, with the same title, dated 17 November 1961. From this item, the Joint Staff withheld two paragraphs in their entirety.

Yet both documents, especially the McNamara memorandum, will be familiar to some readers because they were published in full or nearly in full nearly twenty years ago, in 1996. They appeared in the State Department’s historical series Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-1963, Volume VIII National Security Policy (documents 46 and 54). Moreover, years before its appearance in the FRUS publication, the Defense Department declassified the McNamara memorandum in response to a FOIA request. That earlier release has a few details that were excised in the FRUS version and vice versa, but both were substantially declassified. That makes it instructive to make a side-by-side comparison of the FOIA release, with the version released at the National Archives.

These documents, especially the McNamara memorandum, are historically important. McNamara sent his long memorandum to President Kennedy at a crucial moment in the history of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War nuclear arms race. Even though the U.S. government had just learned from CORONA spy satellite photography that the Soviet Union had only a handful of nuclear-tipped ICBMs (compared to over 160 on the US side), McNamara endorsed the continued build-up of Minuteman ICBMs and Polaris submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Although he argued against a “full first strike capability,” because it would “risk the provocation of an arms race,” the very decision described here meant that the Kennedy administration was engaging in a one-sided arms race in which the Soviet Union would eventually decide to participate massively. It was the recommendations in this document, among others, that McNamara would deeply regret many years later.

Their publicly available status notwithstanding, Department of Defense reviewers (ostensibly with NARA supervision at the National Declassification Center) treated the McNamara and the Lemnitzer memos as if they had never been declassified before and cited 6 different exemptions from Executive Order 13526 to justify the excisions. The exemptions include: (b) (2) weapons of mass destruction, (b) (4) state of the art weapons technologies, (b) (5) war plans in effect, (b) (6) foreign relations, and (b) (8) national emergency preparedness plans, as well as statutory exemptions (Atomic Energy Act). For example, under the (b) (6) exemption, information was withheld that could impair ongoing diplomatic relations with another country. That would make it sound as if the declassification of these documents would be a seriously damaging transgression, yet declassification reviewers during the 1990s and even earlier did not see any such risks to U.S. national security or foreign relations. How could, as DoD declassifiers claim, the release of information about Soviet military installations targeted for destruction impair foreign relations with a country that no longer exists? In any event, the record of declassified evidence on Cold War military targeting continues to pile up and could not possibly damage relations with the successor governments to the Soviet Union.

This preposterous situation raises questions about the quality of the declassification review conducted by DOD reviewers of documents held by the National Archives. For example, what kind of guidance was the reviewer following? One possibility is improper application of declassification guidance (whatever it may be). Another, greater, possibility is that the guidance is so loose that overzealous reviewers can find anything to be properly classified. One more, most likely, possibility is that declassification guidance since the 1990s, has become unreasonably exacting and what could be routinely declassified then is now regarded as properly classified. There may be other explanations, but what happened cannot produce confidence in the DOD’s declassification process, and NARA’s approval of it. Indeed, the massive redactions are classic examples of all-too-often knee-jerk reactions by DOD reviewers against declassifying any substantive nuclear information.

These redactions also raise the question of whether or not reviewers of historical documents consult the FRUS? And if they don’t, why not? And if they did consult the FRUS, what was the point of the excisions? Plainly, declassification reviewers cannot know everything that has been declassified, but when they are reviewing historical records they ought to consult the FRUS. It is, of course, possible that they did and decided they disagreed with the decision taken in the 1990s and made a futile protest by excising the document. But the reviewers should be aware that no matter how sensitive these documents were during the Cold War, the same or similar information on U.S. nuclear delivery systems and their targets during the early 1960s has been declassified in a variety of places by the U.S. Air Force and the Defense Department over the years.

This is not a particularly extreme case; examples from the recent past suggest that over-classification is a characteristic of the Pentagon secrecy system. Yet it is difficult to know what can be done to fix that problem. A few years ago, the Department’s Inspector General’s Office conducted a study of over-classification but it eschewed a close look at declassification outcomes and instead focused on small bore issues. But even a hard-hitting IG report might not have enough traction to spur reform of the Pentagon’s entrenched secrecy culture. Congress could help by imposing legislative requirements, such as the proposal to codify Attorney General Holder’s 2009 memorandum to the agencies. A sensible reform would be to empower the National Archives to oversee agencies’ review processes of historic documents, and ensure that declassification decisions do not fail the “laugh test;” that, however, the Pentagon (not to mention other agencies) would probably resist. In all likelihood, more declassification travesties will occur before such reforms take place.

Trackbacks

Comments are closed.