It all sounds so familiar.

A celebrity turned Republican presidential candidate wins over the white working class with promises to restore American greatness, only to become ensnared in a scandal involving dubious dealings with a hostile regime. As the press digs in, the White House appears flustered, and the Justice Department appoints an independent counsel to investigate the president, as well as trusted members of his National Security Council and former campaign staff.

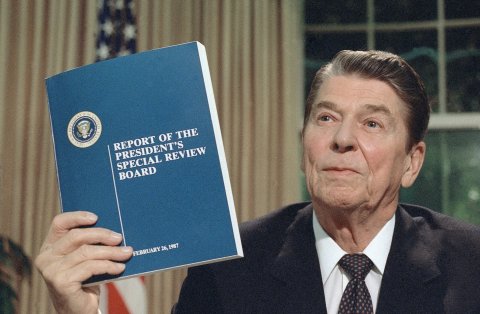

Are you thinking Donald Trump? Well, yes. But also Ronald Reagan. Three decades ago, the Gipper was embroiled in a major investigation, now known as the Iran-Contra affair. The thrust of the scandal: a bizarre scheme that involved the U.S. selling weapons to Tehran—a state sponsor of terrorism, according to Washington—and using the proceeds to covertly (and illegally) fund Contra rebels in Nicaragua.

RELATED: What Brennan couldn't say in the Russia-Trump hearing

Since allegations emerged that the Trump campaign colluded with Russian intelligence during the 2016 presidential election, many have likened the affair to Watergate, the most notorious political scandal in modern American history. And the parallels are clear. Both involve attempts to steal information from the Democratic National Committee, followed by purported cover-ups and efforts to stymie the investigation. Yet many raise the specter of Watergate today not only to measure the sordid nature of Trump's alleged misdeeds, but also as a prediction: Nixon resigned under threat of impeachment, and Trump, the analogy seems to imply, may also be removed from office.

Yet even if investigators—or reporters—uncover evidence of wrongdoing, the president's downfall is far from inevitable, and Iran-Contra should serve as a cautionary tale for those hoping Trump is pushed from office. The criminal probe took more than six years, outlasting a congressional investigation and a separate review by a presidential commission. When it was over, investigators had charged 14 U.S. officials with crimes (leading to 11 convictions or guilty pleas) and uncovered reams of evidence showing Reagan had illegally authorized deals to trade arms for hostages and ordered his staff to keep the Contras together, "body and soul," despite a congressional ban against doing so. The probe never proved that the president knew that funds had been diverted from the Iranian weapons sales to the rebels. But it did find a raft of misconduct by senior administration officials, including a major cover-up.

And yet most of those top aides escaped without formal sanction, often due to restrictions on classified information or because the statute of limitations had run out by the time prosecutors could uncover the evidence. Several mid-level operatives who were convicted in court had their cases reversed on technicalities. Reagan and his vice president, George H.W. Bush, who knew much more about the affair than he initially admitted, suffered temporary drops in the polls. But Bush was elected president just two years after the scandal erupted, and Reagan went on to become a conservative luminary, revered for helping bring down what he called the Evil Empire, the Soviet Union.

The first lesson we can draw from the Iran-Contra affair is that the Trump White House could be in a stronger position than it may seem. Presidents (of both parties) can control the flow of information, even in the face of formal investigations. Sometimes it works better than others. In Trump's case, it's hard to tell what will happen in this regard. Reagan's staff was highly loyal; no one at a senior level broke ranks the way White House counsel John Dean did during Watergate. The Trump White House is already a sieve of leaks. Fidelity, outside the president's innermost circle, seems to be fleeting, and fired FBI Director James Comey is about to testify on Capitol Hill on June 8. What will happen now that subpoenas have started to fly?

A second lesson is that special counsel Robert Mueller will need more than just subpoenas. Congressional investigators tended to eschew bare-knuckle tactics during Iran-Contra, and they regretted it. Even with subpoena power, and despite Reagan's promises of full cooperation, Mueller's equivalent back then, independent counsel Lawrence Walsh, was forced to deal with increasingly frustrating delays by the White House and several federal agencies, notably the CIA. Even the Justice Department repeatedly threw obstacles in Walsh's way, and most egregiously, Cabinet-level officials like Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger (who lied under oath), White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan and even Vice President Bush withheld crucially relevant personal notes for years.

As investigators move forward with the Trump-Russia scandal, what's perhaps most critical is how they—and the press—define it. The classic Watergate formulation, courtesy of Senator Howard Baker, was "What did the president know, and when did he know it?" In Iran-Contra, it was whether Reagan had been aware of, or approved, the diversion of Iranian arms proceeds to the Contras. The attorney general, Edwin Meese, set these parameters at the onset of the scandal. Before Meese did so publicly, however, he had already surveyed everyone in the administration who might have been able—or willing—to give up the Gipper. (Meese later testified that, in the days before the scandal broke, he was acting as the president's "legal adviser," not in his official capacity as the country's top law enforcement officer.) Once he knew the president was safe on that count, his formulation became a convenient way of focusing the spotlight away from other legally and politically sensitive areas. Journalists and investigators took the bait, and Reagan ultimately escaped.

To avoid a similar result in the current situation, investigators should remember this will be a long fight—especially if public pressure mounts and the GOP-controlled Congress is forced to create a select committee. In that case, Mueller can expect several complications. Congressional probes are very different from criminal inquiries. Any significant proceeding will involve public witnesses, some of whom might be granted immunity. That move cost Walsh his most prominent convictions after an appeals court ruled that the trials of Oliver North and former national security adviser John Poindexter were tainted because Congress had immunized them before taking their testimony. If lawmakers seem inclined to do the same for Michael Flynn or former (or current) members of the Trump team, Mueller will need to identify his witnesses and take depositions as quickly as possible—before they testify in public.

RELATED: Donald Trump and the agony of H.R. McMaster

The longer the Trump inquiry drags on, the more likely attention fatigue will set in, and the public will tune out. An irony of all the recent headlines is that they make an extraordinary situation feel normal. They can also give a savvy administration a ready sound bite. Reagan, Bush and their handlers routinely brushed off allegations as "old news" and refused to address their substance. Trump is employing a similar strategy, labeling the stories as "fake" and the press as "the enemy of the people."

Mueller should expect a brutal fight, and his sparkling reputation may not help him. Walsh was a lifelong Republican who had served as deputy attorney general under Eisenhower. When he was appointed independent counsel in late 1986, his encomiums sounded just like Mueller's. But as Walsh pushed on, and the investigation threatened to pull in the vice president, the president's backers began a vitriolic assault against him. Walsh wasn't intimidated, but public pressure did affect the congressional investigation. "Ollie's Army" of enthusiastic supporters made committee members fear possible political backlash at home and helped persuade them to blunt their approach.

Will Trump be able to do the same? A White House aide recently marveled that the president has a "coat of protection that almost seems supernatural." But Reagan—the Teflon president—had something even stronger: He was well-liked. His powerful personal appeal to a majority of voters gave pause to many among the Democratic leadership at a time when few seemed to want another Watergate. Trump, however, is widely loathed by his opponents—and in this hyper-partisan political climate, many of them seem animated by the prospect of his downfall.

Trump's possible motives for colluding with Russia also leave him at a disadvantage. Reagan was universally faulted for his abysmal judgment and execution in the Iran-Contra affair. But few doubted that his aims were patriotic, anti-Communist and humanitarian. The general assumption by the president's critics in today's saga: Whatever the Trump team was up to, it was largely about politics—either winning the race or setting the stage for a softening of American policy.

What Trump does have on his side is Congress. Democrats gained control of both houses just as Iran-Contra hit the headlines. That allowed the opposition to begin a televised, public inquiry, which embarrassed the White House. Today, Trump's party is in charge on Capitol Hill. Much will depend on whether Republicans can hold both houses next year—and if Trump can keep his base together. Doing both would help prevent public hearings or impeachment.

Either way, the best the American people can hope for is that we find out the truth. After Iran-Contra, both the congressional investigating committees and Walsh's team wrote up their findings, and those reports remain among the most important accounts of the affair. Sadly, they also underscored perhaps the main legacy of Iran-Contra: how easy it is for our leaders to abuse power—and get away with it.

Malcolm Byrne is director of research at the nongovernmental National Security Archive at George Washington University and the author of Iran-Contra: Reagan's Scandal and the Unchecked Abuse of Presidential Power.