The commander of a nuclear-armed Soviet submarine panicked and came close to launching a nuclear torpedo during the Cuban missile crisis 60 years ago, after being blinded and disoriented by aggressive US tactics, according to newly translated documents.

Many nuclear historians agree that 27 October 1962, known as “Black Saturday”, was the closest the world came to nuclear catastrophe, as US forces enforced a blockade of Cuba to stop deliveries of Soviet missiles. On the same day a U-2 spy plane was shot down over the island, and another went missing over Siberia when the pilot lost his way.

Six decades on from the “world’s most dangerous day”, last week’s revelation that a Russian warplane fired a missile near a British Rivet Joint surveillance plane over the Black Sea has once more heightened concerns that miscalculation or accident could trigger uncontrolled escalation.

In October 1962, the US sent its anti-submarine forces to hunt down Soviet submarines trying to slip through the “quarantine” imposed on Cuba. The most perilous moment came when one of those submarines, B-59, was forced to surface late at night in the Sargasso Sea to recharge its batteries and found itself surrounded by US destroyers and anti-submarine planes circling overhead.

In a newly translated account, one of the senior officers on board, Captain Second Class Vasily Arkhipov, described the scene.

“Overflights by planes just 20-30 metres above the submarine’s conning tower, use of powerful searchlights, fire from automatic cannons (over 300 shells), dropping depth charges, cutting in front of the submarine by destroyers at a dangerously [small] distance, targeting guns at the submarine,” Arkhipov, the chief of staff of the 69th submarine brigade, recalled.

In his account, first given in 1997 but published for the first time in English by the National Security Archive at George Washington University, the submarine’s commander, Valentin Savitsky, lost his nerve.

Arkhipov said one of the US planes “turned on powerful searchlights and blinded the people on the bridge so that their eyes hurt”.

“It was a shock,” he said. “The commander physically could not give any orders, could not even understand what was happening.”

The risk was, Arkhipov added: “The commander could have instinctively, without contemplation ordered an ‘emergency dive’; then after submerging, the question whether the plane was shooting at the submarine or around it would not have come up in anybody’s head. That is war.”

In his account, Arkhipov played down his role and how close the B-59 submarine commander, Savitsky, came to launching the submarine’s one nuclear-tipped torpedo. However, Svetlana Savranskaya, the director of the National Security Archive’s Russian programmes, interviewed another submarine commander from the same brigade, Ryurik Ketov, who said Savitsky was convinced they were under attack and that the war with the US had started.

The commander panicked, calling for an “urgent dive” and for the number one torpedo with the nuclear warhead to be prepared. However, because the signalling officer was in the way, Savitsky could not immediately get down the narrow stairway through the conning tower, and during those few moments of hesitation, Arkhipov realised that the US forces were signalling rather than attacking, and deliberately firing off to the side of the submarine.

“He called to Savitsky and said: ‘calm down, look they are signalling, not attacking, let’s signal back.’ Savitsky turned back, saw the situation, ordered the signalling officer to signal back,” Savranskaya said. She added that two other officers would have had to confirm any order from Savitsky before the nuclear torpedo could have been launched.

Tom Blanton, the director of the National Security Archive, said the aggressive tactics used by the American submarine hunters contributed to the close shave.

At a conference in Havana in 2002, John Peterson, a lieutenant on the USS Beale, the destroyer closest to the Russian submarine, said he and his crew resented their orders to use only practice depth charges, which just made a loud bang. So they stuffed hand grenades into toilet roll tubes which would hold the pin down for a couple of hundred metres before disintegrating, and causing the grenade to explode next to the submarine’s hull.

The Russian signals intelligence officer on the B-59, Vadim Orlov, said the experience was like being inside an oil drum beaten by a sledgehammer.

The officers and crew were already exhausted. They had sailed all the way from the Russian far north, in submarines that were not adapted for warm waters. Internal temperatures in the engine compartment rose to up to 65 degrees Celsius, with carbon dioxide levels several times normal, and there was very little drinking water, Arkhipov recalled.

Saved ‘primarily because of luck’

The B-59 incident was just one of a cascade of crises that day. A U-2 went missing over Siberia when the pilot lost his bearings, blinded by the aurora borealis and misled by compass malfunction close to the north pole.

Some F-102 interceptor jets were scrambled to protect the U-2, but the joint chiefs of staff who gave the order for their launch were not aware they had been armed with nuclear missiles as a matter of course once the alert level was raised to Defcon 2.

Minutes later, the joint chiefs heard that another U-2 had been shot down over Cuba and assumed it was a deliberate escalation by Moscow. In fact, the order had been given independently by two Soviet generals in Cuba. The joint chiefs were also unaware that there were 80 nuclear warheads on the missiles already in Cuba when they gave their recommendation for the US to carry out airstrikes and then an invasion of Cuba.

The recommendation was overruled by president John Kennedy, as negotiations with Soviet representatives, some of them in a Washington Chinese restaurant, were making progress, leading ultimately to the withdrawal of Soviet missiles from Cuba while US missiles were pulled back from Turkey.

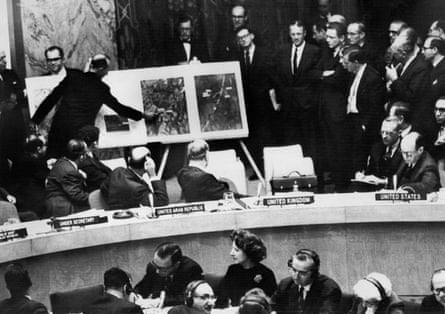

Photograph: ClassicStock/Alamy

Tom Collina, the director of policy at the Ploughshares Fund, a disarmament advocacy group, said Black Saturday “reminds us that the reason we’ve gotten out of things like that in the past is primarily because of luck”.

“We had some good management, we had some good thinkers,” Collina, co-author of The Button, a book on the nuclear arms race, said. “But basically, we got lucky in the closest situations where we could have gotten involved in nuclear war.”

In the incident over the Black Sea on 29 September this year, two Russian Su-27 fighter aircraft shadowed a Royal Air Force Rivet Joint electronic surveillance plane, and one of the Russian planes released a missile.

The Russian air force investigated and claimed it was the result of a technical malfunction. British officials are not convinced it was an accident, but intercepted communications made clear that Russian ground controllers were shocked at what happened, suggesting that if it was a deliberate show of force it was the decision of the pilot, rather than an order from Moscow.

The close encounter prompted an unscheduled visit to Washington on 18 October by the UK defence minister, Ben Wallace, to coordinate responses in the event of a miscalculation or accidental clash between Nato and Russian forces, and to ask for Washington’s agreement for the UK to restart Rivet Joint patrols with fighter escorts.

Collina said the danger of disaster would remain as long as nuclear weapons were part of the military equation.

“The lesson we should have learned in 1962 is that humans are fallible, and we should not combine crises with fallible humans with nuclear weapons,” Collina said. “Yet here we are again.”