Update - February 14, 2025

Washington, D.C., February 14, 2025 - Some 14 years after Anwar al-Awlaki's death in an American drone strike, the Al Qaeda terrorist has become the unlikely subject of a flurry of partisan news and opinion reports attacking the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which the Trump administration is attempting to discredit and shut down. Reports from Fox News, The New York Post, other outlets and social media accounts cite the first document in this 2015 National Security Archive publication to assert that, as the Fox News headline claims, “USAID reportedly bankrolled al Qaeda terrorist's college tuition.”

The facts are actually considerably less damning to the agency than the headline suggests, because the college student would not become a terrorist until many years later. Anwar al-Awlaki was the son of Nasser al-Awlaki, a prominent public figure in Yemen who served as minister of agriculture and as chancellor of two universities. Nasser al-Awlaki had spent 11 years in the United States as a graduate student and young professor and he wanted his son to follow his path. When Anwar enrolled at Colorado State University in 1990 to study engineering, he was hardly religious – he took out the prayer rug his mother kept putting into his suitcase – and certainly no terrorist. After college, he would become an imam, serving in three American mosques and expressing conventional views. He led Friday prayers in the U.S. Capitol, spoke at a Pentagon luncheon, and publicly and privately denounced the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Only after leaving the United States for the United Kingdom did he become steadily more radical, finally joining Al Qaeda in Yemen around 2007. That was 17 years after USAID had approved his scholarship application.

As noted below, Anwar al-Awlaki falsely claimed on a USAID form that he had been born in Yemen in order to get a scholarship from the agency that was reserved for foreign citizens. In fact, he was a U.S. citizen born in New Mexico in 1971 when his father was a student at New Mexico State University. For most of his life, Nasser al-Awlaki had warm feelings for the United States, to which he was grateful for his education and career. His son Anwar, in the last years of his life, reviled the United States and spent his days plotting attacks against the land of his birth. Both are dead now, and they would undoubtedly be amazed to see Anwar's story resurface in an American political dispute.

Original posting - September 15, 2015

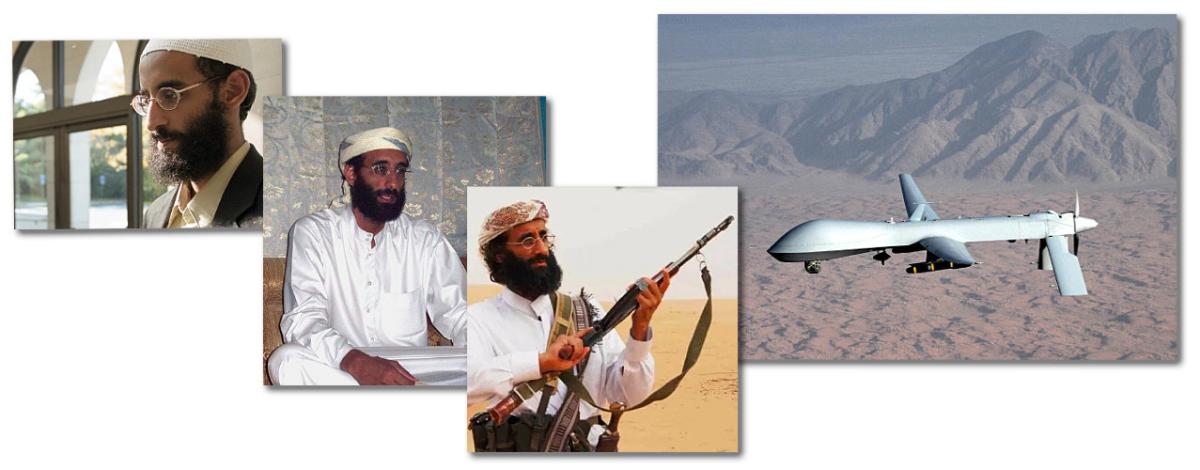

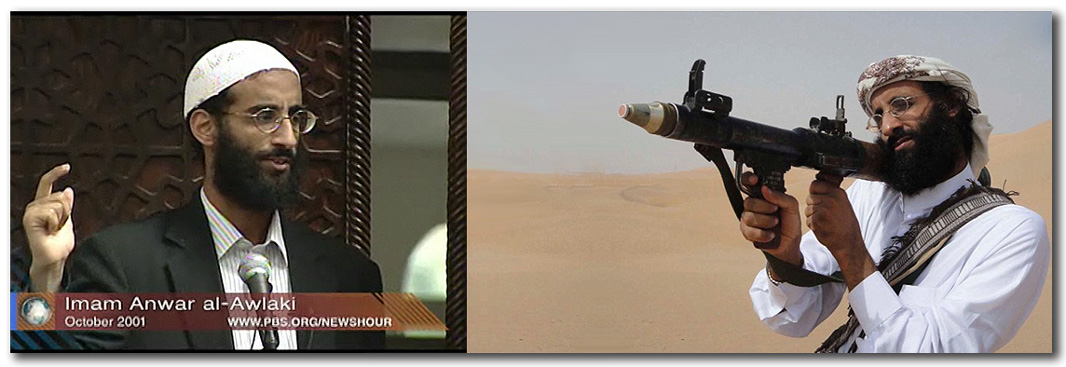

Washington, D.C., September 15, 2015 - Anwar al-Awlaki was an American imam who later became the most influential English-language recruiter for the cause of violent jihad, an ideological journey illuminated by the new book Objective Troy and primary source documents gathered by the author, Scott Shane, and published today by the National Security Archive (www.nsarchive.org).

Awlaki was also the first United States citizen since the Civil War to be hunted down and killed without trial by his own government. His life poses in particularly acute form a vexing question: How does an intelligent, worldly man decide to devote his last years to trying to kill civilians who are strangers to him? His death raises equally pointedly a companion question: How has the fear of terrorism changed America, prompting the government to abandon long-embraced principles in search of safety?

Born in Las Cruces, New Mexico in 1971 when his father was a student at New Mexico State University, Anwar al-Awlaki spent his early years in the United States and spoke English better than Arabic. At the age of 7, he moved with his family to Yemen, where his father, Nasser al-Awlaki, began a long and distinguished public career, including terms as minister of agriculture and university chancellor. When Anwar was 19, his father sent him back to the United States to study engineering at Colorado State University. He graduated and briefly took an engineering job, but he had developed a deep interest in Islam and discovered a talent for preaching, and he soon took a part-time job as an imam in Denver. His success led to a full-time job at a mosque in San Diego, and then in early 2001 to a far larger and more prominent mosque in Falls Church, Virginia, outside Washington. After the 9/11 attacks, which he publicly and privately condemned, Awlaki quickly came to national attention as a Muslim cleric who could both articulate the grievances of Muslims about American foreign policy and explain the mysteries of Islam to Americans suddenly interested in this unfamiliar religion.

But he suddenly left the United States in 2002 after learning that the FBI had followed him on regular visits to prostitutes around Washington and panicking about the possibility that he could be exposed as a hypocrite before his conservative congregation. He moved to London, where he moved in radical circles and took a steadily more intolerant line in his lectures, and then to Yemen, where he was followed by security police and imprisoned for 18 months, at least in part due to the encouragement of the United States.

Shortly after his release in late 2007, he moved to his family’s ancestral tribal territory of Shabwah governate, where he eventually joined Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. He called on all Muslims to attack America and began to participate in active plotting against the United States, helping to recruit and coach a young Nigerian, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who attempted to blow up an airliner on Christmas Day in 2009 over Detroit. He also appears to have played an important role in the dispatch in October 2010 of bombs hidden inside printer ink cartridges on cargo planes headed to the United States. A tip from Saudi authorities thwarted that plot.

By then, after a legal review, President Obama had added Awlaki to the kill list, authorizing his capture or killing on the basis that he posed an imminent threat to the United States. He was killed in an American drone strike in Yemen in September 2011 along with an American acolyte, Samir Khan, with whom he had published the slick English-language Al Qaeda magazine Inspire. Two weeks later, in another drone strike that American officials said was a mistake, his 16-year-old son, Abdulrahman, who had left home to try to find his father, was killed. His death generated far more anti-American anger in Yemen than Anwar al-Awlaki’s death.

Awlaki left behind a hugely influential collection of writings, audio recordings and videos that have surfaced again and again in terrorism cases in the West. His fluent American English, his calm eloquence, and his firsthand understanding of the peculiar pressures on Muslims in the West, seem to have given him an unusual ability to connect with young people looking to religion for a cause. The attention he drew from anxious American authorities over many years meant that many government documents shed light on his life, on the government’s view of him at different stages, and on the legal analysis that justified his extrajudicial execution. Many of the documents below were obtained under the Freedom of Information Act by J.M. Berger of Intelwire, an author and researcher on terrorism; by the conservative Washington organization Judicial Watch; and by the author in researching his book, Objective Troy: A Terrorist, A President, and the Rise of the Drone, published September 15, 2015 by Tim Duggan Books, a division of Crown.

The Documents

Document 1

This form, dated 1990, confirms that Anwar al-Awlaki was qualified for an exchange visa and that USAID was providing "full funding" for his studies at Colorado State University. The document lists Anwar's birthplace incorrectly as Sanaa, Yemen's capital, which he later said was a deliberate falsehood offered at the urging of American officials who knew his father so he could qualify for a scholarship reserved for foreign citizens. In 2002, the inaccuracy would briefly become the basis for an arrest warrant on fraud charges, which prosecutors withdrew.

Document 02a

At least twice, in August 1996 and April 1997, Awlaki was arrested for soliciting policewomen posing as prostitutes in areas of San Diego known for streetwalking. He was married and working in his first full-time job as an imam, leading a conservative congregation. It was a habit that he would resume after moving to a bigger mosque in Falls Church, Virginia, in early 2001.

Document 02b

At least twice, in August 1996 and April 1997, Awlaki was arrested for soliciting policewomen posing as prostitutes in areas of San Diego known for streetwalking. He was married and working in his first full-time job as an imam, leading a conservative congregation. It was a habit that he would resume after moving to a bigger mosque in Falls Church, Virginia, in early 2001.

Document 3

Concerned about Awlaki's contacts with some people under investigation for terrorist ties, the FBI opened a terrorism investigation of him in June 1999, collecting public records such as these from the California Department of Motor Vehicles. But they found nothing alarming and closed the investigation the next year.

Document 4

In the summer of 2000, partly in response to pressure from his father, Anwar al-Awlaki left his job at the San Diego mosque and applied for the doctoral program in educational leadership at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. At the same time he was hired as imam at a far larger and more prestigious mosque, Dar al-Hijrah, in Falls Church, Va. His Ph.D. application included his transcripts from undergraduate and graduate studies at Colorado State and San Diego State, as well as references from American and Yemeni professors whose names are redacted. What is notable is that Awlaki omits any mention of his work as a highly successful preacher from his curriculum vita and his personal essay. His Yemeni reference refers to an agreement to hire Awlaki on completion of his doctorate to run a new department of technical education at the University of Sanaa. So the documents suggest that at the age of 29, despite his success as an imam, Awlaki was seriously considering leaving his religious work for an academic job.

Document 06a

Shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, FBI agents learned that two of the hijackers had prayed regularly in Awlaki's mosque in San Diego, and that one of those hijackers and a third hijacker had turned up at his new mosque outside Washington. Worried that he might have some connection to the plotters, F.B.I, agents interviewed Awlaki at least three times in the weeks after 9/11, once with a lawyer present. He recalled a slight acquaintance with one of the hijackers, Nawaz al-Hazmi, from San Diego, who some others in the congregation thought they remembered seeing visiting the imam in his office. Awlaki condemned the attacks but behaved warily, declining to retrieve his passport or to discuss whether he preached about jihad. The FBI would later conclude there was no evidence Awlaki was in on the 9/11 plot, but the decision to put the imam under 24-hour surveillance would have major unintended consequences.

Document 06b

Shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, FBI agents learned that two of the hijackers had prayed regularly in Awlaki's mosque in San Diego, and that one of those hijackers and a third hijacker had turned up at his new mosque outside Washington. Worried that he might have some connection to the plotters, F.B.I, agents interviewed Awlaki at least three times in the weeks after 9/11, once with a lawyer present. He recalled a slight acquaintance with one of the hijackers, Nawaz al-Hazmi, from San Diego, who some others in the congregation thought they remembered seeing visiting the imam in his office. Awlaki condemned the attacks but behaved warily, declining to retrieve his passport or to discuss whether he preached about jihad. The FBI would later conclude there was no evidence Awlaki was in on the 9/11 plot, but the decision to put the imam under 24-hour surveillance would have major unintended consequences.

Document 07a

Beginning in late September 2001, the FBI placed Awlaki under 24-hour surveillance in an attempt to understand whether he had connections to terrorism. These are a few samples of hundreds of pages of surveillance logs, showing the FBI watchers trailing him and his wife and children to the Natural History Museum and dinner at Phillips Seafood; following Awlaki to the Pentagon, where he was an invited luncheon speaker; and tracking him to George Washington University, where he lectured on Thursday evenings to "UMEMs" - FBI jargon for Unknown Middle Eastern Males - on the life of the Prophet Muhammad, part of his part-time job as the university's Muslim chaplain.

Document 07b

Beginning in late September 2001, the FBI placed Awlaki under 24-hour surveillance in an attempt to understand whether he had connections to terrorism. These are a few samples of hundreds of pages of surveillance logs, showing the FBI watchers trailing him and his wife and children to the Natural History Museum and dinner at Phillips Seafood; following Awlaki to the Pentagon, where he was an invited luncheon speaker; and tracking him to George Washington University, where he lectured on Thursday evenings to "UMEMs" - FBI jargon for Unknown Middle Eastern Males - on the life of the Prophet Muhammad, part of his part-time job as the university's Muslim chaplain.

Document 07c

Beginning in late September 2001, the FBI placed Awlaki under 24-hour surveillance in an attempt to understand whether he had connections to terrorism. These are a few samples of hundreds of pages of surveillance logs, showing the FBI watchers trailing him and his wife and children to the Natural History Museum and dinner at Phillips Seafood; following Awlaki to the Pentagon, where he was an invited luncheon speaker; and tracking him to George Washington University, where he lectured on Thursday evenings to "UMEMs" - FBI jargon for Unknown Middle Eastern Males - on the life of the Prophet Muhammad, part of his part-time job as the university's Muslim chaplain.

Document 8

Worried about Awlaki's contacts with three 9/11 hijackers, the FBI followed him day and night, looking for evidence that he was a terrorist. Instead, agents found that he regularly visited prostitutes in hotels and motels in and around Washington. This paperwork accompanies the videotape of an interview with one prostitute, including an agent's handwritten notes. The woman reported that Awlaki was a repeat customer who said he was from India and was "very nice."

Document 9

Awlaki had left the United States more than two months earlier. But the FBI was exploring whether to charge him in connection with the voluminous evidence agents had accumulated of his patronage of prostitutes, summarized here. This lengthy memo from Pasquale D'Amuro, FBI assistant director for the Counterterrorism Division, to James Baker, Department of Justice Office of Intelligence Policy and Review, requests permission to use evidence gathered under the rules governing intelligence-gathering for a different purpose - to criminally prosecute him. Though prostitution is ordinarily charged under state and local laws, this memo argues that Awlaki had violated the Travel Act, 18 USC 1952, by crossing from Virginia into Washington, D.C. and paying for the services of prostitutes. In the end, authorities chose not to pursue charges.

Document 10

The bureau Washington Field Office, of WFO, found no evidence that Awlaki was involved in terrorism, so it closed the investigation. But the memo again summarized Awlaki's patronage of prostitutes and argued that he had violated the Travel Act.

Document 11a

On October 2, 2003, FBI Special Agent Icey Jenkins, whose name is redacted here, was astonished to get a telephone message from Awlaki. She appears to have passed the message to other agents, including Wade Ammerman, who began a months-long exchange of messages with the imam. Awlaki had seen news reports linking him to the 9/11 hijackers and wanted to meet with agents to persuade them he had no knowledge of the plot or other ties to terrorism. An agent, probably Ammerman, responded that the bureau had been looking for him and wanted to talk because "there are a lot of questions and matters that need to be straightened out." They discussed the possibility of meeting in London in early 2004, but eventually Awlaki stopped replying to emails and the agent and the cleric never met. At the same time, the 9/11 Commission repeatedly sought the FBI's help in arranging an interview with Awlaki. But no interview took place.

Document 11b

On October 2, 2003, FBI Special Agent Icey Jenkins, whose name is redacted here, was astonished to get a telephone message from Awlaki. She appears to have passed the message to other agents, including Wade Ammerman, who began a months-long exchange of messages with the imam. Awlaki had seen news reports linking him to the 9/11 hijackers and wanted to meet with agents to persuade them he had no knowledge of the plot or other ties to terrorism. An agent, probably Ammerman, responded that the bureau had been looking for him and wanted to talk because "there are a lot of questions and matters that need to be straightened out." They discussed the possibility of meeting in London in early 2004, but eventually Awlaki stopped replying to emails and the agent and the cleric never met. At the same time, the 9/11 Commission repeatedly sought the FBI's help in arranging an interview with Awlaki. But no interview took place.

Document 12

Ammerman had spent months pursuing the Awlaki investigation, and five months after it was closed, he was interviewed by 9/11 Commission staff members. Most significantly, Ammerman revealed the reason Awlaki had suddenly left the United States the previous year. The manager of an escort service used by Awlaki had tipped the cleric off to the FBI's inquiries about his visits to prostitutes. Afraid that he might be exposed before his conservative congregation as a hypocrite, Awlaki suddenly left his job as an imam and flew to London, to return to the U.S. only one more time, for a visit in October 2002. Ammerman also mentioned that Awlaki had called the FBI in the fall of 2003, asking for a meeting because he "may want to return to the U.S." The meeting never took place and Awlaki remained overseas, where years later he joined Al Qaeda. Together, documents 11 and 12 suggest that Awlaki, if he had been assured he would not face a prostitution prosecution, might have remained in the United States as a preacher, hinting at a path never taken.

Document 13

Despite closing its terrorism investigation of Awlaki in 2003 for lack of incriminating evidence, the bureau decided it wanted to question him again about the 9/11 hijackers who had worshipped in his mosques and other matters. Awlaki had been arrested in Yemen the previous August, reportedly in connection with a local kidnapping case. But there was also evidence that he might be involved with some foreign militants who knew him as "Abu Atiq." Eventually two agents visited him in mid-2007 in a prison in the Yemeni capital, Sanaa. They do not seem to have gotten any evidence linking him to the 9/11 plot. American officials continued to pressure Yemen to keep Awlaki, an American citizen who had not been charged, in prison.

Document 14

A one-page FBI memo, its contents almost entirely redacted, takes note of the news on December 19, 2007, that "AmCit" - American citizen - Awlaki had been released from prison.

Document 15

On Christmas Day, 2009, a young Nigerian, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, tried to set off explosives hidden in his underwear on a flight from Amsterdam as it neared Detroit. The bomb fizzled and other passengers subdued Abdulmutallab, who later told FBI agents that Awlaki had helped recruit him and coach him for the assignment, including advising him to make sure he was over American soil when he set the bomb off. President Obama asked for a legal review of the possibility of killing Awlaki, an American citizen. In this secret February 19, 2010, memorandum to Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. from the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, the acting head of the office, David J. Barron, assisted by Martin Lederman, another lawyer in the office, argued that killing Awlaki would be legal. Oddly, they refer to him by the respectful title "Shaykh," used by his admirers. They maintain that killing Awlaki as an act of self-defense against terrorism would not violate the Fourth Amendment, the Fifth Amendment or the executive order prohibiting assassination.

Document 16

In a second memo addressed to Attorney General Holder, Barron and Lederman addressed an argument omitted from their first opinion: that killing Awlaki might violate 18 USC 1119(b) or 18 USC 956, two statutes governing killings overseas. They concluded that those laws governed "unlawful" killings, and that killing Awlaki would not be unlawful, because it would be approved by "public authority," as a legitimate police shooting would be.

Document 17

In parallel actions in July 2010, the U.S. Treasury Department and the United Nations Security Council added Awlaki to the official list of designated terrorists. Attorneys for Awlaki's father, Nasser, were preparing to file a lawsuit against the government to try to get Anwar removed from the so-called "kill list," and they believed the official terrorist designation was timed to interfere with the lawsuit. Lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union sued over the matter and the Treasury Department changed the rules to permit the uncompensated legal representation of people on the terrorist list.

Document 18

This November 26, 2010 FBI memo is one example of many over several years taking note of Awlaki's video and audio messages calling for attacks on the West. In this particular message, delivered in Arabic, Awlaki told his audience that no special religious approval was necessary to justify an attack on the United States. "Fighting the devil does not require a religious edict," he said. In multiple messages, Awlaki urged followers to devise their own ways of killing Americans and not to await orders from Al Qaeda leaders.

Document 19

This excerpt of a National Security Agency document taken by Edward Snowden and published by The Intercept praises the cooperation between the military and the CIA in tracking down Awlaki in Al Jawf, a province in the north of Yemen on the Saudi border. A drone strike on September 30, 2011 killed Awlaki, another American Samir Khan, and two other members of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

Document 20

Abdulrahman al-Awlaki, the 16-year-old son of Anwar al-Awlaki, was killed two weeks after his father in a separate American drone strike on October 14, 2011. Abdulrahman, an American citizen born in Denver, had left his grandfather's home in the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, a few weeks before, hoping to find his father. He had no history of militancy, but by some accounts, after learning that an American strike had killed his father, he vowed to join Al Qaeda and try to avenge his father's death. No American official has publicly discussed his death, but officials have said privately that they were targeting an Al Qaeda figure who turned out not to be present and did not know the teenager was there. The State Department form accompanying the death certificate falsely states that his cause of death was "unknown."

Document 21

Nasser al-Awlaki, Anwar's father, twice went to federal court in an effort, as he saw it, to force the United States to live up to its own principles. The first lawsuit, filed in 2010, sought to have his son removed from the so-called kill list and was dismissed. The second, jointly filed by Dr. Awlaki and Sarah Khan, sought to force the government to reveal information on the killings of Anwar al-Awlaki, Abdulrahman al-Awlaki and Samir Khan, Sarah's son. In this April 4, 2014 opinion, United States District Judge Rosemary M. Collyer dismissed the second lawsuit. "In this delicate area of warmaking, national security, and foreign relations," she wrote, "the judiciary has an exceedingly limited role," she wrote.

Document 22

This June 27, 2013 indictment of the younger of the two Tsarnaev brothers for setting off two bombs at the 2013 Boston Marathon is one of many examples of Awlaki's continuing posthumous influence. It notes that Dzhokhar and his older brother, Tamerlan, got their bombmaking instructions from Awlaki's Al Qaeda magazine, Inspire, and that Dzhokhar had downloaded Awlaki's writings. At his trial, prosecutors noted the powerful influence of Awlaki and cited a tweet from Dzhokhar a few weeks before the attacks: "Listen to Anwar al-Awlaki's ... here after series, " Dzhokhar wrote, referring to the cleric's lectures on the afterlife, "you will gain an unbelievable amount of knowledge." Four years after Awlaki was killed, a search for his name on YouTube finds 45,000 videos, and the marathon attack was only one of several dozen plots and attacks in the West in which Awlaki appeared to be an important influence.