Washington D.C., September 20, 2019 — In the aftermath of the September 21, 1976, car-bombing that killed former Chilean ambassador Orlando Letelier and his colleague, Ronni Moffitt, in Washington D.C., four State Department officers began pressing for a policy to force General Augusto Pinochet from power, according to a declassified “Dissent Channel” memorandum published today by the National Security Archive. “It is probable that President Pinochet ordered the assassination of Letelier and others,” the authors wrote in their appeal for an aggressive policy of ending normal relations with Chile until Pinochet was removed. “Our only hope for justice is for the U.S. to take action that will bring it about.”

The “Dissent Channel” is a special--and carefully used--mechanism for State Department officials to provide constructive opposition to established policies. Department procedural regulations define it as“a serious policy channel reserved only for consideration of responsible dissenting and alternative views on substantive foreign policy issues that cannot be communicated in a full and timely manner through regular operating channels and procedures.”

The National Security Archive obtained the Dissent Channel memorandum on the Letelier-Moffitt assassination through a Freedom of Information lawsuit.

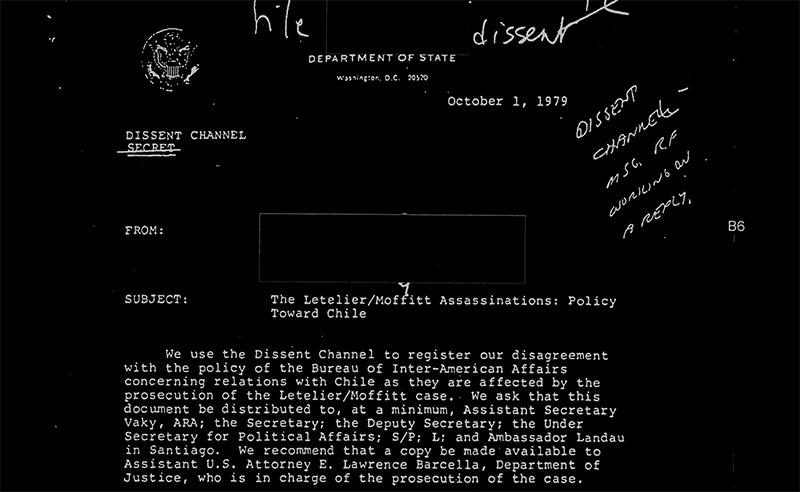

The secret memorandum, titled “The Letelier/Moffitt Assassinations: Policy toward Chile,” was filed on October 1, 1979, shortly after the Chilean Supreme Court rejected a U.S. Justice Department petition to extradite the top two officials of the Chilean secret police, DINA, for their role in the terrorist attack in Washington D.C. CIA intelligence reports revealed that Gen. Pinochet had personally interceded with the chief justice on the court to assure that the extradition request was denied. The four authors of the memorandum objected to the State Department policy of accepting the Supreme Court decision and continuing normal relations with the regime so as not to jeopardize U.S. economic and strategic interests in Chile.

Under Pinochet, Chile was conducting “a campaign of international terrorism,” the authors argued, that required a forceful U.S. response. “Failure of the U.S. to react to this outrage and defiance of our law and power can only bring us into contempt in Chile and elsewhere. Others would not be discouraged from officially-sponsored terrorist acts in our country by governments trying to suppress opposition in exile communities,” they wrote.

The memorandum recommended an explicit official denunciation of Pinochet and the DINA, and a series of sanctions intended to force Pinochet from power and replace him with a more “responsible” military leadership. “The intelligence community has concluded that the removal of Pinochet would result in his replacement by any one of several generals, and present policies would be continued with the probability of a somewhat more rapid transition to civilian government,” the Dissent memo noted. “[Pinochet’s] departure would also remove the primary symbol of Chilean repression and permit much greater political flexibility in dealing with Chile.”

The names of the four authors are redacted in the declassified memorandum, but the positions they held at the State Department are not. Ambassador Francis McNeil, the former deputy assistant secretary for Inter-American Affairs, was one of the drafters. He identified the lead drafter as Robert S. Steven, the former Chile Desk officer, and another official, the Assistant Legal Advisor for Inter-American Affairs, Frank Willis, as a signatory of the Dissent Channel memorandum. The fourth signatory, a State Department lawyer who worked on the extradition request, could not be identified.

“Bob Steven went to the Dissent Channel because it was an established last resort to get decision makers to look more closely at contested policy,” McNeil recalled. “The Chileans knew we knew they had murdered Letelier and Moffitt and expected us to cave. That made punishing the regime all the more necessary, not only for the killings but to prevent others from imitating them. It was, after all, until 9/11 the only postwar foreign sponsored terrorist attack on U.S. soil.”

Several of the dissenters’ recommendations were adopted by the State Department, but their position ultimately failed to influence the Carter administration’s mild response to the Letelier-Moffitt assassination. Other agencies, including the National Security Council, remained hostile to taking a strong stand. “I have never been comfortable with the way State has handled the Letelier case,” NSC Latin America specialist Robert Pastor reported to Carter’s National Security Adviser, Zbigniew Bzezinski ten days after the Dissent Channel memo was filed. “I have been unable to comprehend the transformation of the U.S. from government to prosecutor to judge, which is where we currently are.”

The few sanctions President Carter imposed proved ephemeral; in the end the administration did not aggressively hold Pinochet accountable for the assassination, despite CIA intelligence reports that determined that “Pinochet personally ordered” an act of terrorism in Washington D.C. and spearheaded the cover up of his regime’s role in the Letelier-Moffitt assassinations. Those reports remained secret for decades, and were only declassified at the request of the Chilean government of Michelle Bachelet on the 40th anniversary of the assassination in September 2016.

The National Security Archive today posted the Dissent Channel memorandum, along with the official State Department “receipt” of the document. In addition, the posting includes a previously declassified memorandum from National Security Council Latin America specialist, Robert Pastor, to National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, on how to determine sanctions against Chile.

Read the documents

Document 1

FOIA

On October 1, 1979, four State Department officials filed a "Dissent Channel" memorandum pressing for a U.S. policy to "force Pinochet to step down" from power because of his role in the September 21, 1976, car-bomb assassination of former Chilean ambassador Orlando Letelier and his colleague, Ronni Moffitt, in Washington D.C. The officials-their names are redacted but their titles were declassified--challenged the policy promoted by the State Department's Bureau of American Republic Affairs (ARA) to "entrust the matter" to the Chilean military courts. Those tribunals, according to the dissenters, had "a record of farce and injustice" since the 1973 coup. Relying on the Chilean courts to judge the regime, as they wrote, would only "accommodate the defiance of Pinochet" who, they argued, likely "ordered the assassination of Letelier and others." The U.S. government had no "vital interests" in Chile, they asserted, more important than standing up to an act of international terrorism in Washington D.C. "Failure of the U.S. to react to this outrage and defiance of our law and power can only bring us into contempt in Chile and elsewhere. Others would not be discouraged from officially-sponsored terrorist acts in our country by governments trying to suppress opposition in exile communities," they wrote. The dissent memorandum outlined a new, forceful, policy approach that included: publicly identifying General Pinochet and his secret police, DINA, as responsible for the Letelier-Moffitt murders; withdrawal of the U.S. ambassador in protest; and forceful pressure on the Chilean military to oust Pinochet and replace him with "more responsible (albeit military) leadership."

Document 2

State Department Virtual Reading Room

This document is an official "receipt" of the Dissent Channel memorandum. Paul Kreisberg, Acting Director of State's Policy Planning Staff, commends the authors for their "thoughtful" memo, which he notes will be copied and distributed as far up as the Secretary of State. Kreisberg advises that a formal response is being coordinated by a member of the Policy Planning staff, Richard Feinberg. (The response, however, has not yet been located in the State Department archives.)

Document 3

Clinton Administration Chile Declassification Project

In a confidential memorandum to National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, his deputy for Latin America, Robert Pastor, advises on how the Carter administration should determine a response to the Pinochet regime's obstruction of justice and lack of cooperation in the Letelier-Moffitt assassinations. Pastor appears hostile to the State Department's position that U.S. policy should hold Pinochet accountable for an act of terrorism in Washington D.C. "I have never been comfortable with the way State has handled the Letelier case," he reports. "I have been unable to comprehend the transformation of the U.S. from government to prosecutor to judge, which is where we currently are." But he is equally critical of Secretary of Defense Harold Brown's argument that military-to-military relations with the Pinochet regime should not be affected by any sanctions. Pastor advises that the U.S. government should determine what evidence exists on the regime's role in the car-bombing and what the U.S. policy objectives are in imposing sanctions on the military government.

Document 4

Clinton Administration Chile Declassification Project

After intense debate within the Carter White House about how to respond to the Pinochet regime’s cover-up of the Letelier-Moffitt car-bombing, National Security Advisor Brzezinski conveys President Carter’s decision to Secretary of State Cyrus Vance. The argument of the Dissent Channel authors to hold Pinochet responsible for the atrocity in Washington D.C. is rejected in favor of a mild set of sanctions that include a small reduction of embassy staff, suspension of joint military naval exercises, and an official U.S. statement of disapproval for the regime’s failure to properly investigate the act of terrorism.