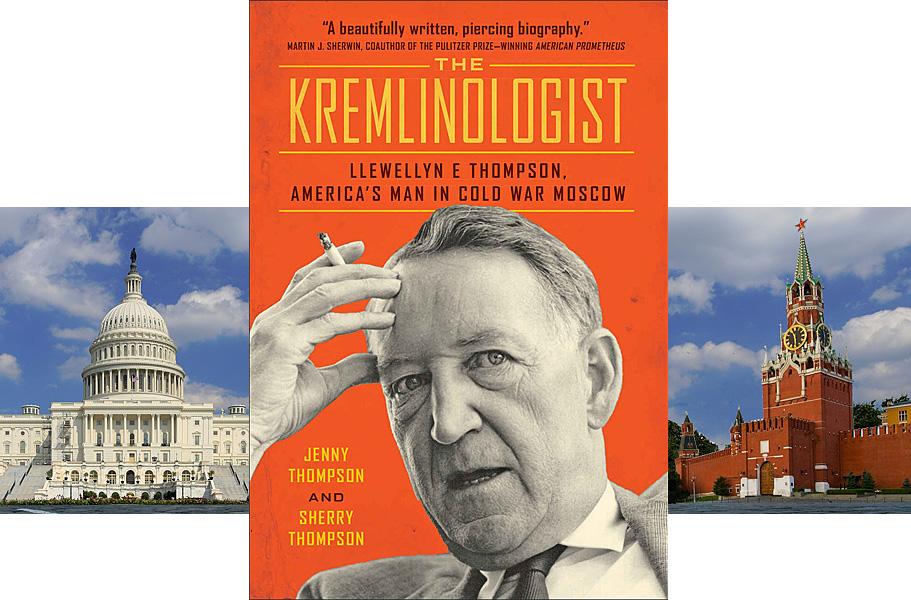

Washington, D.C., November 19, 2018 - Today, the National Security Archive is publishing a set of documents to commemorate the life and achievements of long-time diplomat and presidential adviser Llewellyn Thompson and highlight the publication of a biography of him written by his daughters, Jenny Thompson and Sherry Thompson, The Kremlinologist: Llewellyn E. Thompson, America's Man in Cold War Moscow (Johns Hopkins Nuclear History and Contemporary Affairs, 2018). The posting includes never-before-published translations of Russian memcons with Khrushchev and Thompson’s cables from Moscow.

* * * * *

Introduction to the posting The Kremlinologist

By Jenny and Sherry Thompson

Llewellyn Thompson was a career diplomat whose life went from the wilds of the rural Southwest at the beginning of the 20th Century to the inner sanctums of the White House and Kremlin. He became an important advisor to Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon and a key participant in major 20th century events - the birth of the U.N., the Truman Doctrine, the Austrian State Treaty, Nixon’s visit to Moscow, Khrushchev’s visit to the U.S. and the summit with Eisenhower creating the “spirit of Camp David,” the beginning of détente. This was followed by the shooting down of Gary Powers’ U-2, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War, the Glassboro summit, the Six Day War, and the first serious disarmament SALT talks.

Thompson joined the Foreign Service in 1928 and served early tours in Ceylon and Geneva, where he was a representative at the International Labor Organization. He was posted to Moscow as a young Foreign Service Officer during World War II, from 1941 to 1944. When the diplomatic corps and most of the Soviet government (except Stalin and Molotov) fled to Kuibyshev during the German siege of Moscow, Thompson stayed behind to take care of U.S. and allied interests, for which he later earned the Medal of Freedom.

During this time, Thompson recognized that his government did not understand the nature and structure of the Soviet government. He wrote a long paper trying to explain this and Soviet foreign policy, and gave it to his colleague, George Kennan, to edit. Thompson and Kennan were close friends during the Wartime period and remained friends, although not as close as in those days. Kennan kept Thompson’s paper for a year and then sent it back unaltered. He wrote his own Long Telegram six months later. The critical differences between the two treatises were the timing and the conclusions. Thompson’s was written in 1944 before President Roosevelt’s death (April 1945) and Kennan’s just after Stalin’s strident speech of February 9, 1946. Thompson concluded that, if the U.S. government could understand the characteristics of the Soviet system and foreign policy, it could still be possible to deal with them. Thompson’s paper has never seen the light of day, until now.

In 1950, Thompson was posted again overseas, first to Rome and then to Austria as ambassador and high commissioner. There he secretly spearheaded the negotiations on the Trieste settlement between Italy and Yugoslavia, and helped finalize the Austrian State Treaty, reestablishing Austrian sovereignty and providing for the only instance of the complete removal of Soviet troops from a previously occupied territory in Europe. Just before leaving Austria to become ambassador to Moscow, the Hungarian uprising of 1956 forced thousands of refugees across the border into Austria, their plight taking a back seat to the Suez Canal crisis unfolding at the same time.

Thompson’s forthrightness and wartime experience in Moscow helped him develop a special relationship with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev realized that Thompson was trying to work toward better relations between the two countries and that he was always straightforward with the Soviet premier. This allowed for fascinating and often frank meetings between the two men. During the eventful times in his five-year appointment, Thompson saw the timid beginnings of détente. He strongly advocated for cultural and scientific exchanges, was the first American official to appear on Soviet television, the opening of the American Exhibition in Moscow, including the infamous Kitchen Debate between Vice President Nixon and Khrushchev. He also advocated for Khrushchev to come to the United States. Unfortunately, this was followed by the Gary Powers U-2 incident which proved the death knell for the follow-up four-powers summit in Paris. Contrary to the stated excuse for delaying the U-2 spy plane over Soviet territory until May Day, the weather covering Powers’ flight plan was no worse and sometimes better than May 1st during the original window in which the flight was supposed to take place. Thompson was furious; he did not know about the U-2, having been told those flights had been cancelled. He didn’t think Eisenhower knew about the flight either.

Thompson encouraged Kennedy to meet Khrushchev in Vienna, despite the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion because he had witnessed the personal contact between Eisenhower and Khrushchev in September 1959 and believed it had been beneficial. However, the Berlin Crisis, which wove through the entire Cold War, affected this and virtually everything else at that meeting. At the Eisenhower/Khrushchev summit at Camp David, first steps were taken to at least discuss the issue. The subsequent 1961 Vienna summit was important because Khrushchev would test Kennedy’s resolve on Berlin and a meeting between the two men could possibly find a way to put the crisis on hold. In preparation for the summit, a series of briefing cables to the Department were sent from Bonn and from Thompson in Moscow. The Bonn Embassy wanted Kennedy to be tough and back Khrushchev against the wall. Thompson warned against such a tactic. He advised Kennedy not to saw off the limb onto which Khrushchev had climbed. Following Bonn’s advice might leave the president between the choice of “all-out war or ignominious retreat.”

Years later, some academics concluded Thompson had ill-prepared Kennedy for the summit because he wrote that Khrushchev would deal with Berlin in a “sweetness and light atmosphere.” In fact the opposite was true. For some reason part of the sentence where Thompson used that expression had been left out of the quote. Actually, Thompson was warning the department that brushing over Berlin in sweetness and light was a typical Khrushchev tactic when discussing recognition for East Germany, and if he tried that in Vienna Kennedy should be prepared to force the issue and make sure the U.S. position on Berlin was clear. In hindsight, Thompson believed that Kennedy came though on this in Vienna.

Thompson’s long experience in negotiating with Communists allowed him to correctly anticipate Khrushchev’s reactions during the Cuban Missile Crisis. This made him more than just another man around the table. As Secretary of State Dean Rusk described, it made him “our Russian in the Room.” Perhaps Thompson’s greatest contribution during those 13 days in October was to shift the perspective from striking Cuba with or without prior notification to Khrushchev, to getting Khrushchev to stop the shipments of additional materiel to Cuba with a quarantine, and then to get the Soviets to take the missiles out themselves under threat of a strike.

After receipt of the two Khrushchev letters, on “Black Saturday” of the Cuban Missile Crisis (October 27), the president and his closest advisors had narrowed the inevitable options to get the Soviet missiles out of Cuba down to two: either a military strike would occur the following Tuesday or Kennedy would capitulate to Khrushchev´s demands and trade the NATO missiles in Turkey for the Soviet ones in Cuba. Kennedy looked at the men sitting around the oval table and said, “We’re not going to get these weapons out of Cuba, probably… by negotiation. We’re going to have to take our weapons out of Turkey.” To everyone´s surprise Thompson, a normally reticent participant in discussions unless specifically addressed, now said, “I don´t agree, Mr. President.” Thompson still believed the Soviets would remove their missiles from Cuba without the trade. Thompson´s intervention won him the unusual distinction of being branded both a Hawk and Dove. So what was he? Henry Brandon, the Washington correspondent for The Sunday Times of London, called him the Cold War Owl.

Writing the book was for us quite an adventure and self-educating process. We needed to teach ourselves how to do archival research, how to footnote and reference, how to question secondary sources, and look for the primary source that would clarify our doubts. We needed to learn about the history of the events we were dealing with. In the end we both decided that even if the book did not go further than a self-published record for the family, it was well worth the effort and left us both better educated, wiser, and with a sense of understanding for the times we had lived through and to better assess the events unfolding today. That is why we are so pleased to share some of the documents that we used through the National Security Archive, which was so useful to us during our research.

The documents

Document 01

Thompson Family Archive

In the fall of 1944, Thompson drafted a 44-page paper, in which he tried to explain the nature of the Soviet regime and the concepts and process of Soviet foreign policy with the purpose to help U.S. policy makers engage the Soviet Union cooperatively in post-war reconstruction. Thomson expresses hope that the Soviet Union will “at least for a few years take its place in the family of nations and cooperate with other states upon a more normal basis than has been the case in the past.” In a comprehensive and perceptive analysis, Thompson points to factors that might be less well understood in the West, such as the organic nature of the Soviet state, its closed and secretive character, its suspiciousness of foreign powers, the role of the Communist party and the security organs, the power of propaganda and lack of information and contact with outsiders. Thompson sent the paper to George Kennan for suggestions and “polishing” in order to present it to the State Department. Although the paper was never “polished” and sent to the State Department, a reader can see that Kennan’s “Long Telegram” from 1946 benefitted from insights from Thompson’s “Long Paper.”

Document 01A

Thompson Family Archive

Almost a year after Thompson sent his paper to Kennan, he sends it back to Thompson saying that he simply does not have time to help him on his paper, but calls it “a really valuable document.” Kennan muses that the State Department may not have a high opinion of him [Kennan] any longer and that he should “go home at this juncture and lead a different life for a while.”

Document 02

This cable from Embassy Moscow to the State Department is Thompson’s account of his meeting with Khrushchev on May 4, 1959, as published by the State Department Historian’s Office in the FRUS documentary series. The Russian memcon of this meeting, in the Russian State Archive of Contemporary History (Fond 52, Opis 1, File 580), is more detailed but does not differ substantively from the cable (only the first part of the conversation is covered in the cable). Thompson requests to see Khrushchev to ask for information on a U.S. airplane that entered the Soviet airspace on September 2, 1958, and, according to U.S. intelligence, was shot down by the Soviets. Khrushchev denies the shooting, saying it was an accident and that six bodies were recovered and given to U.S. authorities. In the second part of the conversation Khrushchev and Thompson discuss the future visit of Vice President Richard Nixon (what would become the so-called kitchen debate) and lament the lack of information about each side in the two countries. Thompson says the United States has been moving closer to the Soviet Union, even in ideology, lately, but there has been no reciprocity on the Soviet side. Khrushchev says that he would be willing to stop jamming U.S. radio broadcasts if relations improved. Thompson treats the premier with respect but also with a candor that Khrushchev clearly appreciates.

Document 03

Russian State Archive of Contemporary History, Fond 52, Opis 1, File 581

Thompson asks to meet with Khrushchev to discuss an RB-47 aircraft incident when U.S. pilots were taken into custody by the Soviet authorities. The conversation begins with an endless lecture by Khrushchev, full of outbursts against American “monopolistic capitalism,” and including comments on the provocation from the Francis Gary Powers U-2 overflight, denunciations of U.S. behavior in the world, and the suggestion that the Soviet Union “could just as well announce its right to launch missiles with blank charges into the United States for target practice.” At the same time, Khrushchev expresses his belief that Eisenhower did not know about the U-2 flight, that it was all CIA director Allen Dulles and “and the military's provocation,” and that he respected Eisenhower even though “being an inexperienced political leader, he does not concern himself much with real work, but instead plays golf.”

Khrushchev talks about the benefits of the Communist system, expresses his conviction that Thompson’s grandchildren will live under Communism but that it would be their own people, not the Soviet Union, who would “bury capitalism.” Thompson pushes back, saying Khrushchev did not convince him that Communism is a better system. They talk about the elections in the United States, the economy, the hope to start a new and better stage of U.S.-Soviet relations – a real peaceful coexistence. In the end, Thompson comes back to the fates of the RB-47 pilots, and eventually Khrushchev comes around, saying “in any case, our government will discuss this issue, and I believe that, most likely, we will hold the same stance as you,” meaning that the pilots will not be tried before the U.S. presidential elections and might be released after the elections. The conversation gives the reader a sense of the real trust and respect that the Soviet leader felt toward Thompson, treating him as a colleague and a valued interlocutor. Among some humorous outbursts, one can see the genuine Khrushchev, in all his peasant smarts and bluster, but also a real commitment to peace.

Document 04

At the beginning of the Kennedy administration, Thompson writes this cable to help the incoming administration understand the Soviet leadership, their beliefs and intentions, and to suggest ideas for U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union. He formulates the fundamental question at the beginning of the cable: whether the United States should “resolve principal issues by negotiation [with the Soviet Union] in serious manner; meaning being prepared take risks in order reach agreements,” and answers that any other way would end in war. He points out that the Soviet leaders are believers in Communism who “have almost religious faith in their beliefs,” but they are also nationalist and have tensions with the Chinese Communists (Thompson says he does not “exclude eventual complete break between Soviet and Chinese Communists”). He expresses his respect for Khrushchev, who, in Thompson’s opinion is “probably most pragmatic and least dogmatic of all” the Soviet leaders. He describes the Soviet people as “pro-American,” and not interested in the international goals of Communism. In his assessment of Soviet military strength he sees it as formidable but does not posit Communism as a primarily a military threat because, in his view, the Soviet leadership “recognized major war no longer acceptable means achieving their objective.”

Document 05

Thompson is recalled to Washington for consultations on Soviet policy at the beginning of the new Kennedy administration. During the meeting with top Soviet experts in the Cabinet Room with President Kennedy, Thompson gives his analysis of the Soviet government, economy and the military. He says that the Soviet government is strong, that the economy is growing, and that there is a strong consumer demand, especially for new housing, although he sees serious problems in Soviet agriculture. Regarding the military, he believes that although it is formidable, its conventional strength is exaggerated by American experts. In response to Kennedy’s question, Thompson provides very precise policy recommendations: “first, and most important, we must make our own system work. Second, we must maintain the unity of the West. Third, we must find ways of placing ourselves in new and effective relations to the great forces of nationalism and anti-colonialism. Fourth, we must, in these ways and others, change our image before the world so that it becomes plain that we and not the Soviet Union stand for the future.”

Document 06.

Department of State, Central Files 611.61/5.2461 (redacted version published in FRUS, complete version here)

Thompson’s May 24, 1961, discussion with Khrushchev is striking for the candor on both sides. The Soviet leader used the excuse of attending an American “ice revue” to invite the American ambassador and spouse to his box, and then to dinner at the intermission (they never returned to the show). Khrushchev is preparing for what would be the Vienna summit with President Kennedy. Thompson demonstrates a remarkable ability to connect with the Soviet leader in this conversation over the Berlin stalemate and Khrushchev’s threat to sign a separate peace treaty with East Germany that would end U.S. occupation rights in West Berlin. Khrushchev keeps pushing, pushing, but Thompson brings him practically to a halt with the deployment of honesty. “He threw out possibility of our each reducing our troops in Germany by say one-third. I said we would far rather deal with Russians than leave it to Germans to have responsibility for keeping peace in this area and said ‘I refuse to believe that your Germans are any better than ours.’ K laughed, reached over table and said impulsively, ‘Let’s shake on that.’ Afterwards he seemed somewhat embarrassed by his remark.”

Document 07.

Department of State, Central Files 611.61/5.2461 (previously unpublished)

This follow-up cable for the Secretary’s “eyes only” adds Thompson’s commentary to his report from the noon cable (Document 06) about the Khrushchev ice revue talk the night before. Thompson warns Washington that the Soviet leader seems “deadly serious” about doing a separate peace treaty if another agreement on Berlin is not reached, and recommends that Kennedy discuss the Berlin problem with Khrushchev only with interpreters present because of the difficulty the Soviet leader would have in front of his aides.

Document 08.

Department of State, Central Files 611.61/5.2461 (previously unpublished)

The ice revue dinner conversation (Document 06) gives Thompson lots of material that Washington needs to know, especially in view of the upcoming Vienna summit. This second follow-up cable Thompson says is “minor and supplemental” but the details are memorable. Khrushchev confesses something that would have made him extremely vulnerable during Stalin’s purges of the 1930s – that his brother had supported the Whites in the Russian Civil War and been killed at that time. The Soviet leader says he is taking the train to Vienna in order to see the expected bumper crop in Ukraine, and to do some fishing in Kiev. In a sort of preview of the August 1961 decision by the Soviets and East Germans to build the Berlin Wall, Thompson says neither “we or West Germans wanted refugees to leave.” Indeed, when the Wall goes up, there is some relief in Washington and Bonn, in contrast to the later denunciations. Thompson notices that despite an earlier Novosibirsk conversation in which Khrushchev said his doctor forbade hard liquor, the Soviet leader took 5 or 6 brandies during dinner.

Document 09.

Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XIV, Berlin Crisis, 1961–1962, Document 28

Thomson writes this cable to explain how he sees Khrushchev’s position on Berlin in the context of Khrushchev’s domestic pressures. The discussion of this cable and a larger scholarly debate about Thomson’s advice to Kennedy on the eve of the Vienna Summit is in the sidebar essay linked here.

“Summit Mythology” by Jenny Thompson and Sherry Thompson

In this essay, the Thompson sisters reflect on the debate regarding Thompson’s advice to Kennedy [in Document 09, the “Sweetness and Light Cable”] on negotiating with Khrushchev in Vienna and especially his views on the Berlin issue.

Document 10

Russian State Archive of Contemporary History, Fond 52, Opis 1, File 582

This amazing conversation takes place as Thompson is preparing to leave the USSR at the end of his tour as ambassador. Khrushchev wants to express his appreciation for Thompson’s work in Moscow and hopes that he will continue to work for improvement of U.S.-Russian relations. Unbeknownst to Thompson, at the same time, Soviet missiles and 40,000 Soviet troops are moving to Cuba, in the operation codenamed Anadyr – which would soon provoke the most dangerous nuclear crisis of the 20th century.

Reading this memcon today, one can hear Khrushchev barely able to contain his knowledge of the secret operation. He mentions that the USSR is sending shipping vessels to Cuba and might even keep them there. At one point, he bursts out: “You are not pleased with our good relations with Cuba, and we are not pleased with your bases surrounding us.” The conversation covers several important subjects of U.S.-Soviet relations, mainly disarmament, the shooting down of the U-2, and most importantly, the status of West Berlin. Khrushchev talks emotionally and explosively about his intentions regarding signing a peace treaty, repeating it at least five times: “We will sign the peace treaty, thus making access to West Berlin by the occupation powers impossible.” It is not surprising that after such an outburst in his last conversation with Khrushchev, Thompson believes that the main factor in the decision to send missiles to Cuba is West Berlin – as he argued during the discussions in October 1962. But with hindsight, one can see at the end of the meeting Khrushchev saying: not before the elections, and probably not this year, and maybe not next year either.

Document 11

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, White House Tape Recordings, Transcribed by Jenny and Sherry Thompson.

Between April and the beginning of June 1963, after the Cuban Missile Crisis, President Kennedy had two separate lines of contact with Premier Khrushchev. These have been conflated in some accounts. To seal his legacy, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan pressed Kennedy to jump-start efforts toward a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty – either through a summit or a joint emissary to the Soviet Union. The other channel was a set of secret communications between Kennedy and Khrushchev and a decision to send a special emissary to discuss broader issues and misunderstandings with Khrushchev. This second track begins when Thompson and Rusk meet with the president, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy on April 5, 1963, to discuss a “talking” letter from Khrushchev that the attorney general had refused to accept from Soviet ambassador Dobrynin because it was so harsh.[1]

The discussion centers around who to send – Rusk or Robert Kennedy – and the necessity of finding a good cover story. They decide that only the men in the room would know that the emissary was on a serious mission. The reason for the mission is their worry that Khrushchev might act on the threat in his letter to shoot down one of the U-2 planes that is still conducting overflights of Cuba, just six months after the Cuban Missile Crisis. At the conclusion of the discussion on April 5, they decide that Thompson will talk to Dobrynin in an informal way to tell him Kennedy is preparing a letter to Khrushchev to calm the situation, and that Thompson will sound Dobrynin out on a possible emissary and to restart the pen-pal correspondence. What follows is a description of what was captured by the White House taping system from that meeting, with some of it directly transcribed by Jenny and Sherry Thompson.

Notes

[1] The document that RFK refused to accept was made available to the State Department by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Department of History and Records in 1995 and is available in the FRUS online. 1961-1963, Vol. VI, Kennedy-Khrushchev Exchanges, Doc. 93

[2] Excerpt from Sorensen article in Der Weiner Gipfel 1961 Kennedy – Chruschtchow, Stefan Karner, Barbara Stelzl-Marx, Natala Tomilina, Alexander Tschubarjan, et al editors, Studien Verlag; Auflage: zahlreiche s/w-Abbildungen (28. April 2011): “Later, when I read the detailed transcripts of the summit talks, both in preparation for the President’s speech later that summer and subsequently in drafting my 1965 book, Kennedy, I found no bullying or contempt. Neither man retreated from his respective ideological views and national interests, neither showed any disrespect or incivility for the other.”

Excerpt from Thompson and Thompson presentation at Der Weiner Gipfel 1961 Kennedy – Chruschtchow: When it was over, Thompson reported that the conference had gone ‘as expected.’ Given that Kennedy was not prepared to help Khrushchev put out the fuse he had lit under himself in starting the Berlin Crisis and that Khrushchev had nothing to offer in the way of a test ban or disarmament agreement, there was not much to expect beyond the two leaders getting an impression of each other. He believed Kennedy had come out all right because he reacted very well to Khrushchev´s threatening attitude over Berlin. It had an important effect on Khrushchev. Schlesinger is said to have quoted Thompson as thinking Kennedy overreacted. He probably meant Kennedy had overreacted in thinking that he had done badly when actually the main message Khrushchev got was that there was going to be no compromise on access rights to Berlin. This was a good thing; otherwise it could have been ‘very dangerous indeed.’… For Bohlen and Thompson, Khrushchev’s ideological speeches were nothing new, so much so that Bohlen fell asleep in the middle and had to be woken up by Thompson kicking him in the ankle.”

From Bohlen, Charles E., Witness to History. W. W. Norton, 1973, page 482: “The general impression that emerged from the meeting was that Khrushchev was trying to intimidate the new president with his tough talk. I did not receive that impression.” (He goes on to say that the talk left a lasting impact on Kennedy and conditioned him for crises in Berlin and Cuba.)

[3] Authors’ 2010 telephone conversations with Theodore Sorensen; and Thompson Oral History for Kennedy Library