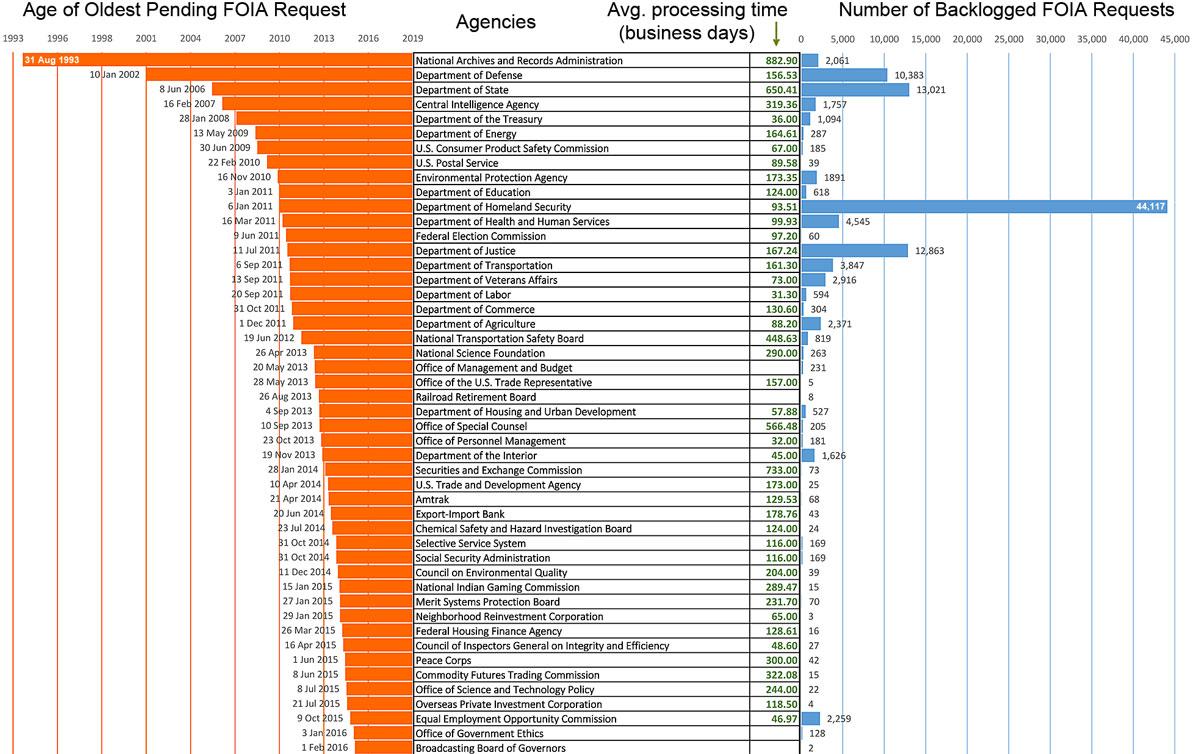

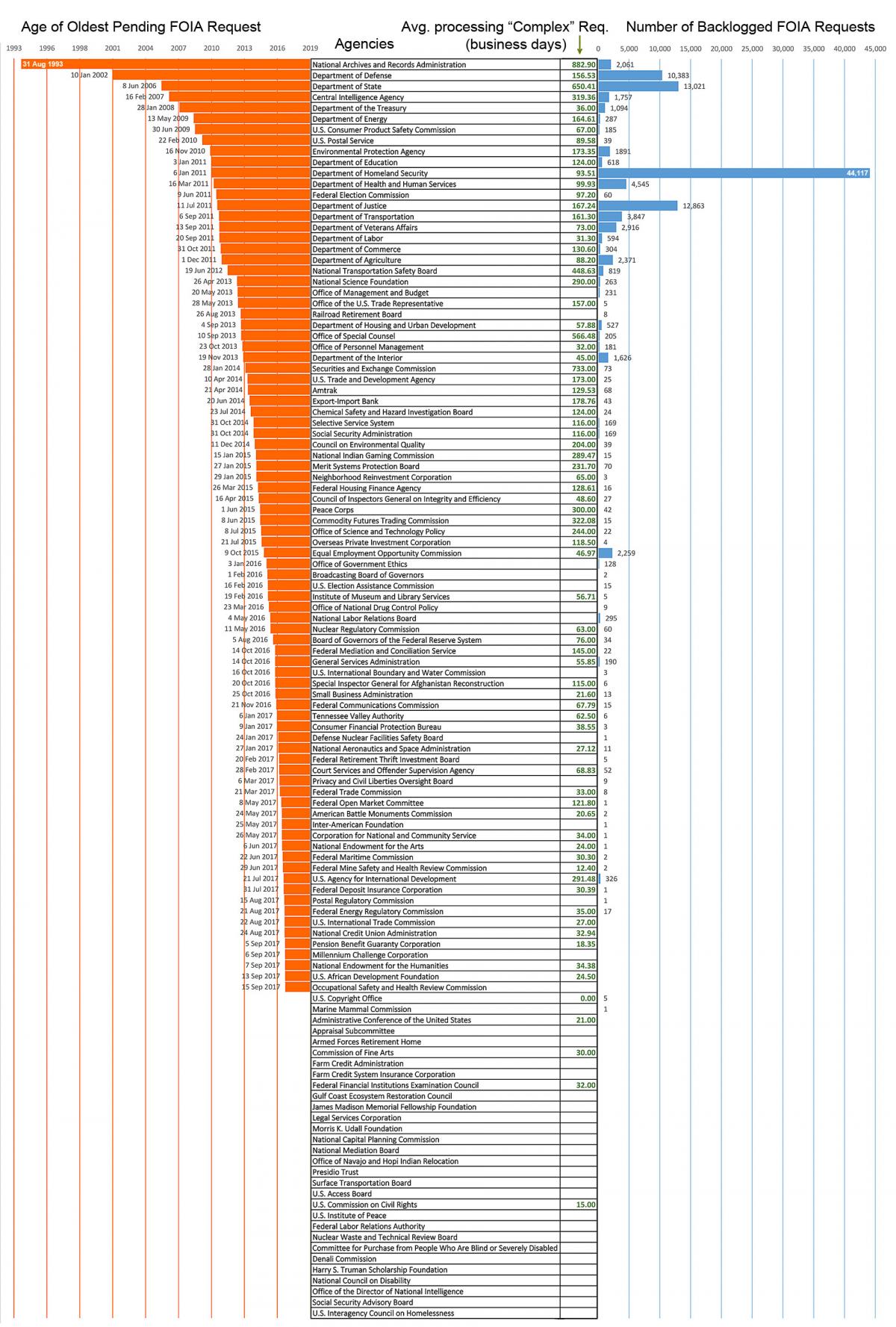

Washington, D.C. March 8, 2019 – Five federal agencies have FOIA requests more than a decade old and one, the National Archives and Records Administration, has a FOIA request more than 25 years old, this according to a National Security Archive Audit released today to mark the beginning of Sunshine Week. The survey also found there is a correlation between agencies with the oldest FOIA requests and those with the largest FOIA backlogs.

The Archive Audit team parsed through the annual FOIA reports federal agencies are required to submit to the Department of Justice’s Office of Information Policy and found that while many agencies appear to have used new reporting requirements as a tool to address the oldest agency FOIA requests, others have let decades-old requests linger. The Archive used the Fiscal Year 2017 reports because they were the most comprehensive collection available at the time of publication due to the delay caused by the government shutdown, and will update this posting once the complete set of FY 2018 reports are available.

The key driver for FOIA requests that could be renting cars by now and growing backlogs is the “referral black hole.” Agencies currently refer or consult on any FOIA request in which it feels another agency or agencies may possibly claim ownership of, or “equity” in, the information within the records. This daisy chain of referrals can often result in decades-long delay, and the re-review of the same document by multiple agencies is redundant, costly, and inefficient.

In 2003, concerned with the tremendous age of its outstanding FOIAs, the National Security Archive created the “Ten Oldest FOIA Request” metric to illustrate the quantity of unfulfilled requests held by government agencies. In 2006, the Department of Justice directed all agencies to include the date of their oldest pending request in their annual FOIA report, and the OPEN Government Act of 2007 codified the requirement that all agencies report their oldest open requests. Back then, the oldest request was only 18, old enough to enlist in the Army. Congress intended the reporting of oldest requests to be a management tool and incentive for agencies to clear the worst of their backlogs; clearly the agencies at the top of our chart are not fulfilling Congress’ intent and not managing their worst offenders.

In 2011, a National Security Archive audit found and identified the owner of the then oldest FOIA request in the federal government, Dr. Monte Finkelstein. Upon being appraised of this “honor” he wrote to the Archive, “When I made the original request in 1993, I was a Professor of History at Tallahassee Community College and was writing my book, Separatism, the Allies and the Mafia; the Struggle for Sicilian Independence, 1943-1948. It was published in 1998…I finally gave up waiting for any other materials that I may have requested suspecting that for reasons beyond my control the material was not going to be declassified for my use. ...I would be interested to know if anything will be done to speed up the process of answering FOIA requests. I know that it would be very helpful to historians if they did not have to wait 18 years to get materials”.

In addition to insufficient agency attention to – and budgets for – FOIA, referrals and consultations are a likely factor in many, if not all, of the ancient FOIA requests. The holder of the oldest FOIA request, the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, should take the advice from the federal Public Interest Declassification Board, which recommended that NARA’s National Declassification Center must recognize that “clinging to manually-intensive [referral] processes diverts increasing dwindling resources …There must be an understanding and agreement that the current practice of having one, two or more persons conduct a laborious page-by-page declassification assessment for each record under review is an unsustainable practice.”

The National Security Archive believes that a presidential memorandum still on the books from the previous administration already relieves NARA of the requirement to beg other agencies to help it with its FOIA requests. The memo states “further referrals of these records are not required except for those containing information that would clearly and demonstrably reveal [confidential human sources or key WMD design concepts].” Previous large declassification review projects have also shown that a “one set of eyes–one decision” review is possible, effective, and desirable. Both the JFK Assassination Records Review Board and (to a lesser extent) the Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group have shown that declassifiers can effectively be unleashed from the bonds of mandated equity re-review.

If NARA believes it needs more authority to declassify the historic records in its holdings, it should ask Congress for it. A line stating “The National Archives and Records Administration shall have declassification authority for any and all records in its possession” should do the trick.

Other agencies should begin by following the 2014 Department of Justice Office of Information Policy-issued guidance on “Referrals, Consultations, and Coordination” which instructs agencies to improve tracking requests, communicate better with requesters, and introduced the requirement that an “agency receiving the referral [should] place the records in any queue according to that request receipt date.”

But as our audit shows, this guidance is not enough. If Congress wanted to fix the “referral black hole,” it could pass a law stating: “An agency must unilaterally process any record requested under FOIA, if any FOIA referral or consultation takes longer than one year.”

The National Security Archive has conducted 17 FOIA Audits since 2002. Modeled after the California Sunshine Survey and subsequent state "FOI Audits," the Archive's FOIA Audits use open-government laws to test whether or not agencies are obeying those same laws. Recommendations from previous Archive FOIA Audits have led directly to laws and executive orders which have: set explicit customer service guidelines, mandated FOIA backlog reduction, assigned individualized FOIA tracking numbers, forced agencies to report the average number of days needed to process requests, and revealed the (often embarrassing) ages of the oldest pending FOIA requests. The surveys include:

- Agencies Struggling to Respond to FOIA Requests for Email

- The Ashcroft Memo: "Drastic" Change or "More Thunder Than Lightning"? (2003)

- Justice Delayed is Justice Denied: The Ten Oldest Pending FOIA Requests (2003)

- A FOIA Request Celebrates Its 17th Birthday: A Report on Federal Agency FOIA Backlog (2006)

- Pseudo-Secrets: A Freedom of Information Audit of the U.S. Government's Policies on Sensitive Unclassified Information (2006)

- File Not Found: 10 Years After E-FOIA, Most Federal Agencies are Delinquent (2007)

- 40 Years of FOIA, 20 Years of Delay (2007)

- Mixed Signals, Mixed Results: How President Bush's Executive Order on FOIA Failed to Deliver (2008)

- 2010 Knight Open Government Survey: Sunshine and Shadows: The Clear Obama Message for Freedom of Information Meets Mixed Results (2010)

- 2011 Knight Open Government Survey: Glass Half Full: Freedom of Information Change, But Many Federal Agencies Lag in Fulfilling President Obama's Day One Openness Pledge (2011)

- 2011 Knight Open Government Survey: Eight Federal Agencies Have FOIA Requests a Decade Old (2011)

- Outdated Agency Regs Undermine Freedom of Information (2012)

- Freedom of Information Regulations: Still Outdated, Still Undermining Openness (2013)

- Half of Federal Agencies Still Use Outdated Freedom of Information Regulations (2014)

- Most Agencies Falling Short on Mandate for Online Records (2015)

- Saving Government Email an Open Question with December 2016 Deadline Looming (2016)

- Three out of Five Federal Agencies Flout New FOIA Law