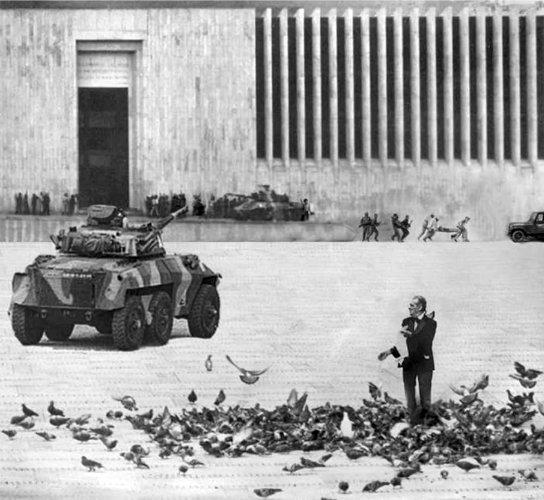

Washington, D.C., December 6, 2024 - Yesterday, Colombian President Gustavo Petro announced that he has asked the United States to expedite the declassification of archival records on the 1985 Palace of Justice case. The request is an important step forward for human rights advocates seeking to clarify the motivations and actions of the M-19 insurgents who stormed the building on November 6, 1985, and the Colombian government’s responsibility for those who died in the fire that tore through the seat of Colombia’s judicial branch and for the disappearances that occurred in the aftermath.

He pedido desclasificar los archivos secretos de los EEUU para el año 1985. Espero que EEUU ayude a la verdad. https://t.co/q5kRdiW3M1

— Gustavo Petro (@petrogustavo) December 6, 2024

The request was welcomed by Helena Urán Bidegain, author of Mi Vida y El Palacio (My Life and the Palace), a memoir of her own investigation of the disappearance of her father, Carlos Urán, an auxiliary magistrate who is believed to have been tortured and murdered by the Colombian Army after surviving the initial assault on the building. The latest edition of the book includes cites a number of declassified documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act by the National Security Archive that raise important questions about the U.S. role in the episode that remain unanswered.

In seeking the records, Petro is complying in part with a recommendation made by Colombia’s truth commission, which said that the president should ask the U.S. to declassify records relating to human rights violations in Colombia, including the Palace of Justice case, among others. President Petro’s request to President Biden is also made in compliance with the 2014 ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which found the Colombian state responsible for deaths and disappearances during the episode and ordered Colombia to satisfy the victims’ right to know the truth about what happened (the “Right to Truth”).

The case is of particular interest to President Petro, who was a member of the M-19 insurgent group that seized the Palace on November 6, 1985, but was detained at the time and was not involved in the takeover of the building. The request for declassification comes less than two months before President Joe Biden leaves the White House and turns the office over to Donald Trump.

The Palace of Justice case has long been a focus of the Archive’s Colombia documentation project. Last year, as part of a call by Urán and others for Petro to request such a declassification, the Archive published a collection of U.S. records on the case, highlighting some important revelations and raising questions about documents and portions of documents that remain secret.

U.S. military reports included in the posting confirm that Colombian military intelligence knew about the M-19 assault at least a week in advance and that Colombian President Belisario Betancur “gave the military a green light, telling them to do whatever was necessary to resolve the situation as quickly as possible.” The CIA ultimately found that Betancur acted mainly out of “fear that failure to act forcefully would anger military leaders.” A U.S. Embassy cable written years later found that the Colombian Army was responsible for deaths and disappearances during the Palace of Justice case.

Other documents raise more questions than they answer. One describes how U.S. Southern Command dispatched a C-130 aircraft and a six-person “support team” carrying high-powered C4 explosives and detonating cord to Bogotá during the crisis, raising questions as to whether these were used just a few hours later to blow open a large metal door on the third floor of the building—an explosion that was determined to have caused many civilian casualties. The U.S. also pondered a Colombian request for “asbestos suits” so that security forces could continue “pressing their efforts” inside the “fire gutted building,” but redactions in these records make it hard to tell what became of these requests.

The U.S. has also failed to declassify any contemporaneous records about the people who were disappeared in the wake of the assault and whose surviving family members have waited years to learn the truth about what happened to their loved ones.

Also of interest are the still-hidden lessons that the U.S. drew from the outcome of the Palace of Justice episode, especially as a means of understanding the fragile state of civil-military relations in Colombia at the time. In its post-mortem on the case, the U.S. Embassy said that the Colombian military was anticipating “the swing of political opinion towards more forceful tactics against insurgents” and that they would have “a free hand” against the guerrilla groups when Betancur left office the next year.

“President Petro’s request for a U.S. declassification on the Palace of Justice case is an important step in Colombia’s long-overdue reckoning with one of the most searing episodes in its history,” said Michael Evans, director of the Archive’s Colombia documentation project. “President Biden should seize this opportunity to use declassified diplomacy to help shed light on one of the country’s most important and most debated human rights tragedies.”