Washington D.C., April 22, 2019 - Black blotches mar the surface of the Mueller Report like measles cases tracked on a map of Brooklyn. Some 176 of the 448 pages feature at least one redaction, according to the Washington Post count, and 10 pages are blacked out in full.

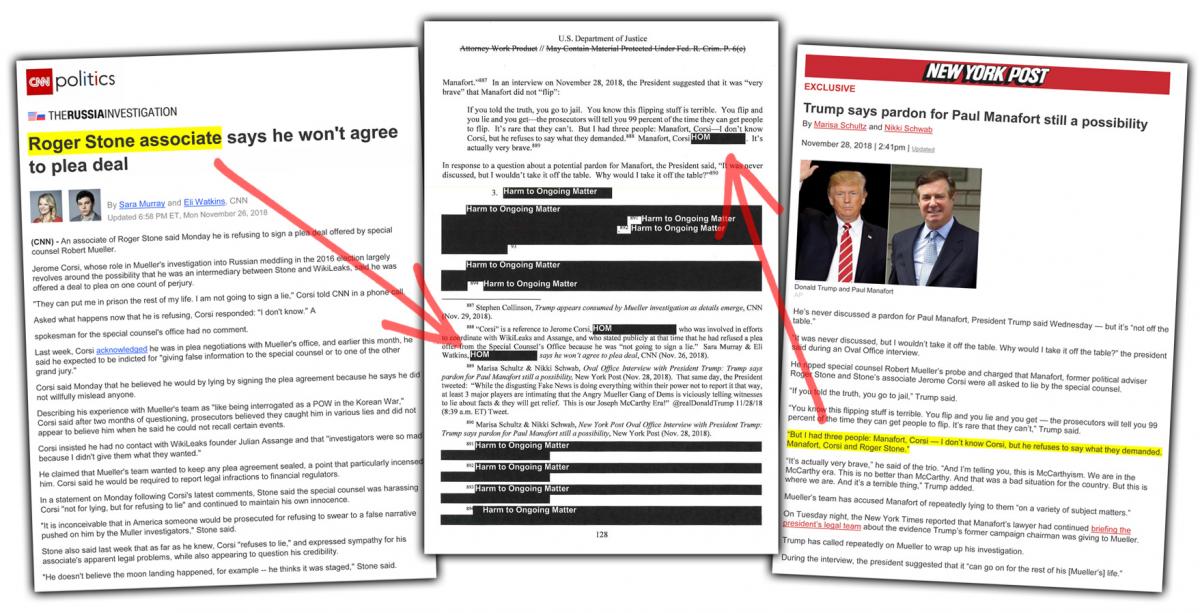

The Justice Department redactions are on their face overdone. The censors working for Attorney General William Barr even blacked out people’s names that appear in published news accounts or in public quotations. For example, on Volume 2, page 128, there’s a black blotch and the code “HOM” [claiming Harm to Ongoing Matter] over a name that President Trump told the New York Post in a direct quote during a November 2018 interview, a quote the Post subsequently published. The name is Roger Stone, the currently indicted former partner of convicted felon and Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort.

A blotch labeled HOM also covers the first few words of an actual news story title listed in the footnotes on that page – a title you can look up on CNN, “Roger Stone associate says he won’t agree to plea deal.” The following two pages of the Mueller Report are covered with black, deleted in full. Stone again?

These unwarranted deletions are black marks on Barr’s record and on the credibility of the Justice Department. The idea that leaving in any mention of Stone would somehow do harm to the ongoing prosecution cannot be true, given the amount of information the government has already had to file in court to indict Stone, not to mention the vigorous counter arguments made by a vociferous Stone and his defense team.

The Stone censorship also proves that – of all four of the censorship categories claimed by Barr – HOM is the most subjective. HOM black outs make up the bulk of the Barr redactions, 427 of them, compared to 358 cuts for “Grand Jury” materials, 94 for “Investigative Techniques,” and 74 for “Personal Privacy.”

In Barr’s defense, grand jury materials do comprise a relatively objective category. The underlying documents would likely be so labeled. And in general, the rule of grand jury secrecy holds, but with some major exceptions. Judges have ordered the release of historically important grand jury testimony from the Rosenberg and Hiss Cold War espionage cases, and from the attempted World War II prosecution of the Chicago Tribune for publishing leaks, after historians and organizations like mine petitioned the courts. The Ferguson, Missouri prosecutors used their discretion to open the grand jury testimony in that controversial shooting case so the public could see the conflicting evidence that prevented an indictment of the police officer perpetrator.

The saving grace of having so many HOM redactions in the Mueller Report is that they are time-bound. Whenever those cases actually reach trial and the prosecution rolls out its evidence in court, including the grand jury testimony, those sections of the Mueller report should immediately be released.

On “Investigative Techniques,” the Justice Department seems on far more solid ground than on “Harm to Ongoing Matter.” The released report contains on page 13 of Volume 1 a useful summary of Mueller’s techniques: more than 2800 subpoenas, nearly 500 search and seizure warrants, more than 230 orders for communications records, almost 50 orders for pen registers, 13 requests to foreign governments under the Mutual Legal Assistant Treaty, almost 500 witness interviews and 80 in front of the grand jury.

Those “orders for communications records” would likely be the most sensitive in this category, because those go to the government’s capacity and legal basis for intercepting phone calls and emails and messages. Several sections of the Mueller text apparently rely on such communications intercepts, such as the discussion on page 149 (13 invocations of “Investigative Techniques”) of attempts by the head of the Russian sovereign wealth fund, Kirill Dmitriev, to get in touch with Trump transition personnel immediately after the election.

For those of us who prefer unredacted history, the most disquieting of many troubling moments in the Mueller Report comes courtesy not of Barr’s censors, but of President Trump’s disdain for record-keeping at all. In Volume 2, page 117, “The President then asked, “What about these notes? Why do you take notes? Lawyers don’t take notes. I never had a lawyer who took notes.” [White House counsel Donald] McGahn responded that he keeps notes because he is a ‘real lawyer’ and explained that notes create a record and are not a bad thing. The President said, “I’ve had a lot of great lawyers, like Roy Cohn. He did not take notes.”

Apparently President Trump intends to put the censors out of business, by the simple expedient of not keeping any records (like notes of his meetings with foreign heads-of-state Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un).