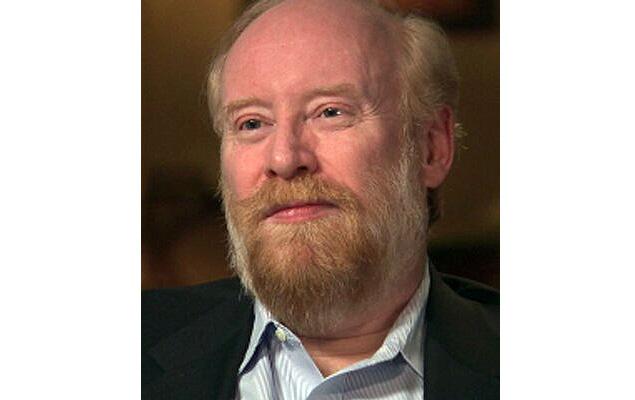

Washington, D.C., September 10, 2018 – Staffers at the National Security Archive were saddened by the news of Matthew Aid’s untimely passing on August 20, 2018. We had the good fortune to work with Matthew and benefit from his decades-long efforts to uncover the secretive world of U.S. signals intelligence (SIGINT) collection. As an independent historian, his research, including wide-ranging FOIA requests and archival sleuthing, and in-depth interviews resulted in two important books, The Secret Sentry: The Untold History of the National Security Agency and Intel Wars: The Secret History of the Fight Against Terror, published by Bloomsbury Press. His publications and other contributions brought him well-deserved recognition as an accomplished historian of intelligence and national security policy.

Growing up in the era of Watergate and the Church Committee, and interested in military history, Matthew began making trips to the National Archives to collect recently declassified documents. He also liked to play war games. National Security Archive fellow John Prados recalls that when he was in graduate school at Columbia University and designing board war games as a free-lancer, he met Matthew, then a high-school student living in New York City, at a company named Simulations Publications. Matthew agreed to playtest board games, such as Panzerkrieg, that John was developing. Matthew shared with John recently declassified Army G-2 documents from World War II. John writes that “I was sad when Matt left for Beloit College since he'd been one of my two best playtesters.”

Years later, in 2005, Matthew made his first contribution to the Archive when he was researching his book on the National Security Agency’s (NSA) history. Matthew had developed extensive contacts with agency staffers, who told him about a history of the Gulf of Tonkin incident that higher level officials had refused to declassify. According to the study by Robert J. Hanyok, erroneous translations of intercepted North Vietnamese messages had been covered up and distorted by higher-level officials so that the intelligence could be used to confirm that a second attack on a U.S. ship in the Gulf in August 1964. After Matthew learned that the study had been bottled up, he informed New York Times journalist Scott Shane who wrote about the cover up in a major story. The NSA soon declassified Hanyok’s study, which the National Security Archive published, giving Matthew full credit for his important discovery.

The next year Matthew made an outstanding contribution to transparency and open government by revealing the U.S. National Archive’s program of re-classification of records that had been in the open, declassified stacks. As it turned out, officials at the National Archives had made secret agreements with the CIA and the Air Force giving them carte blanche to withdraw documents that they contended were still sensitive. Matthew’s discovery of large numbers of withdrawal notices for records that had been previously available produced a New York Times front page exposé in February 2006, a major posting by the National Security Archive, an audit by the government’s Information Security Oversight Office (ISOO), and termination of the secret program. Present and future historians of intelligence and national security issues owe Matthew a debt of gratitude for this discovery.

Ironically, the fame resulting from Matthew’s discovery led a detractor who had once worked at NSA to send the Washington Post the results of a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) release detailing Matthew’s Air Force court martial in 1985 for misuse of classified documents and impersonating an officer.[1] J. William Leonard, the Director of ISOO who oversaw the 2006 audit of the withdrawal of records from public access at NARA, criticized the Post for publishing negative information that “served no useful public purpose”: “it would have taken me all of two seconds to conclude that it was irrelevant to the matter at hand, as it should be to The Post and its readers.”

Matthew’s contributions to the history of U.S. intelligence and to transparency in government ended too soon. We will miss the benefit of his wide-ranging knowledge on intelligence and nuclear weapons records at the National Archives. We are glad that we had him as a friend and colleague.

To the Archive, Matthew made direct and outstanding contributions. He authored, co-authored or contributed to several postings on our website, prepared postings alerting readers about his books, and served as project director and co-director of two document sets for the Digital National Security Archive (DNSA) database. Here are links to items that illustrate Matthew’s contribution:

Tonkin Gulf Intelligence "Skewed" According to Official History and Intercepts

The Secret Sentry Declassified

National Security Agency History of Cold War Intell Activities

INTEL WARS The Lessons for U.S. Intelligence From Today's Battlefields

Matthew was also project director or co-director for two Digital National Security Archive publications:

Electronic Surveillance and the National Security Agency: From Shamrock to Snowden

U.S. Intelligence and China: Collection, Analysis and Covert Action

Documents

Note

[1] Matthew did not dispute the episode though he later described it as less serious than it might have appeared – he had full clearances to view the classified documents but had inappropriately taken them home, and in the second instance had simply been “trying to impress” a young woman.