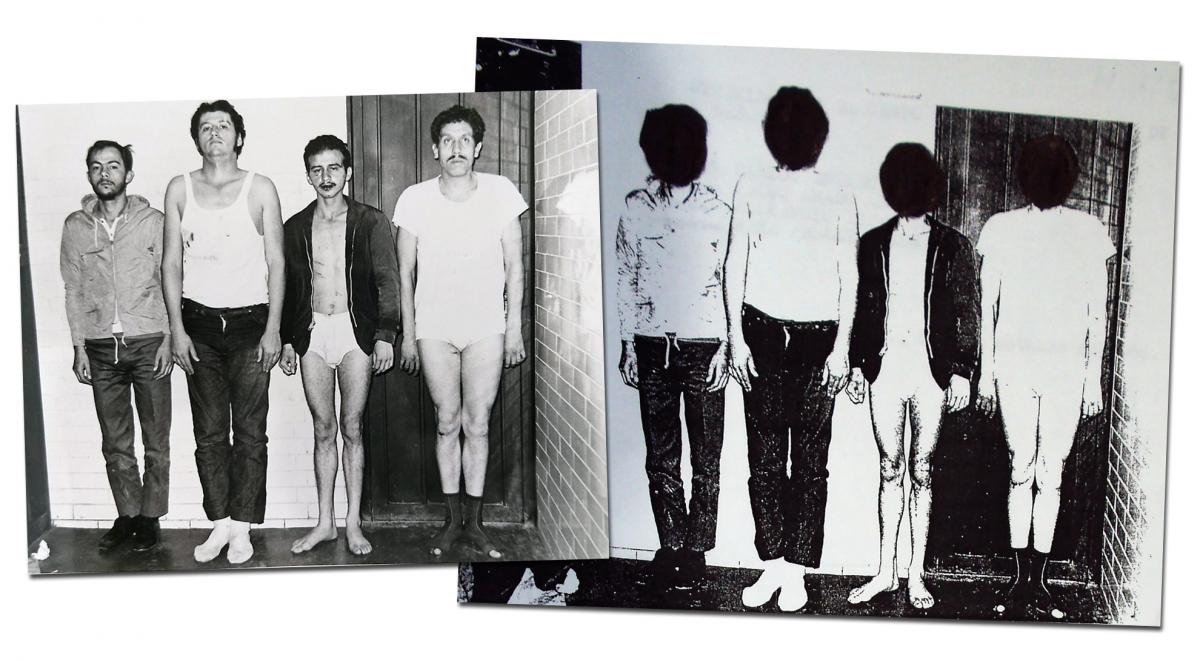

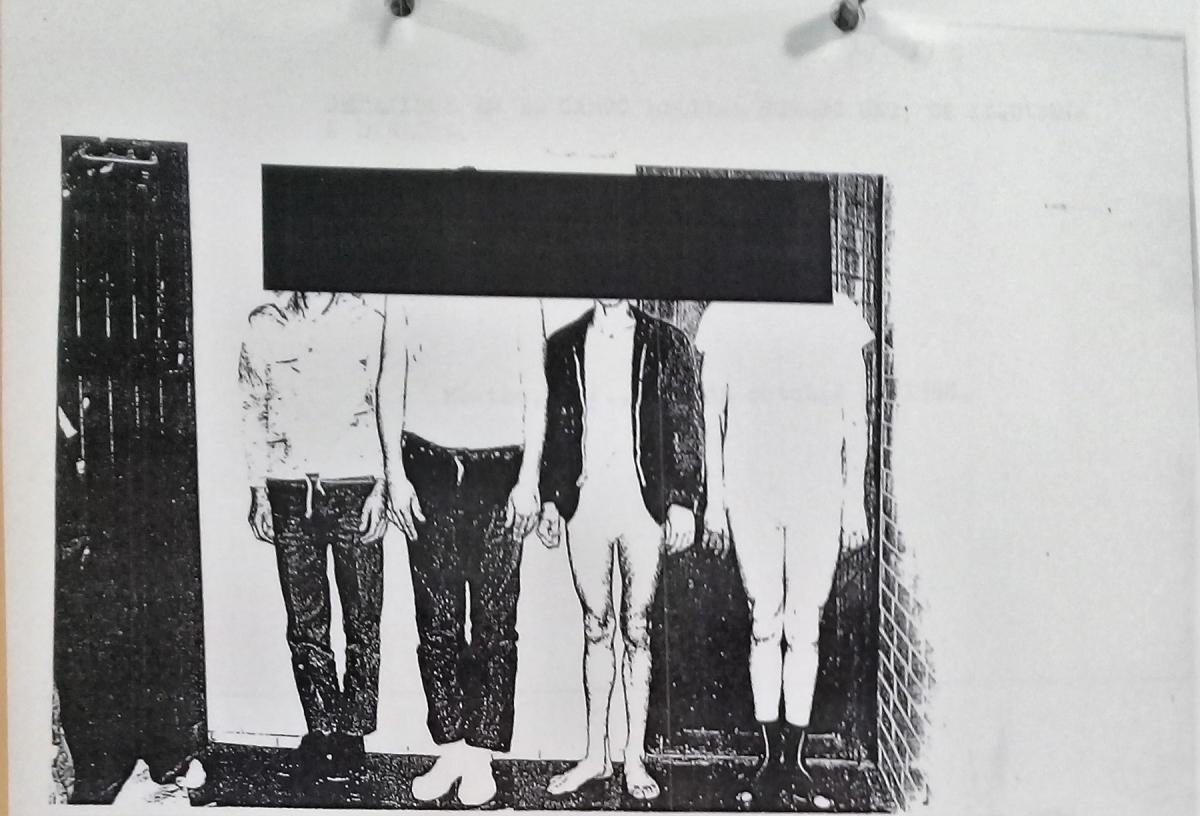

Original photo (left) and re-classified “public” version (right) depicting detainees in Military Camp Number One, 3 October 1968. (Credit: AGN archives, Dirección General de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociales, Caja 2911-A and AGN archives, Dirección Federal de Seguridad, Problema Estudiantil, Tomo 25 y 26)

Washington D.C., October 2, 2018—Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of the notorious Tlatelolco massacre, when the Mexican government killed dozens of students and bystanders protesting the authoritarian regime in a public plaza at Tlatelolco, Mexico City. Across the country, citizens are commemorating the event with marches and rallies, conferences, exhibitions, and performances.

But even as Mexico acknowledges the legacy of the student movement of 1968 and grieves the long-ago slaughter of its young leaders, the Mexican government has quietly removed, censored, and reclassified thousands of previously accessible archives from that era. The General Archive of the Nation (AGN) defends its actions by citing a 2012 Archives Law and new, stricter requirements to protect personal privacy. But the results are heavy-handed to the point of absurdity, as even the most widely known and published records about Tlatelolco and other flashpoints of the dirty war have now been rendered illegible by censorship.

The AGN’s reclassification project is a retreat to Mexico’s old, tired reflexes of disinformation and denial when it comes to politically threatening histories. It reflects the determination of State power to limit or distort what people understand about the past. And it goes hand-in-hand with five decades of impunity for those who planned and executed the crackdown on student protesters in 1968 and injustice for their victims.

No one has ever been held accountable for the mass slaughter of civilians by Mexican military and security forces. At the time, President Díaz Ordaz lied about who was responsible, blaming radical students for igniting the confrontation by shooting at army troops that surrounded the crowd. In fact, independent investigations have concluded that Díaz Ordaz’s chief of staff – on the president’s order – placed snipers inside apartments overlooking the plaza to fire into the crowd.[1] The ensuing chaos was intended to provide justification for sweeping arrests.

In 2001, President Vicente Fox appointed a special prosecutor to investigate the massacre at Tlatelolco, along with multiple other cases of forced disappearance, illegal detention, torture and extrajudicial killing committed by State agents during the 1960s-80s. The office accomplished next to nothing, according to most outside observers. It never held public hearings. No arrests were made. Its single important accomplishment – publication of an extensive report on Mexico’s dirty war, with a chapter on the Tlatelolco killings – was erased from government websites days after its release. The special prosecutor’s office closed shortly afterwards, in November 2006.[2]

Fox did make one decision that dramatically altered what we knew about Tlatelolco. In 2002, the president announced the opening of a special collection in the Mexican national archives dedicated to government records about the dirty war. The gesture was made in the spirit of the political transition that had brought him to power and in response to rising demands from civil society to confront past State repression. A powerful report issued by the National Human Rights Commission shortly after Fox took office, documenting the forced disappearance of hundreds of Mexicans in the 1970s and early 1980s, was another catalyst.

The historical records ordered declassified by the president came from the political intelligence branch of the Interior Secretariat, the old domestic intelligence agency Dirección Federal de Seguridad (DFS), and the Secretariat of Defense. When the AGN opened the doors to its new reading rooms, a handful of researchers showed up to get a first look; I was one of them. Here’s what I wrote about the experience in 2003:

It is an astonishing collection. The millions of pages of records and ephemera bear witness to a massive spying and disinformation campaign, including documents on the state’s clandestine surveillance of universities, the Communist Party, guerrilla groups, and suspected subversives; thousands of transcripts of illegal wiretaps against the PRI’s political opponents (and sometimes its allies); copies of the anonymous hate mail and slanderous letters penned by government employees in an effort to intimidate their enemies or destroy their careers; clips from an unsigned political column that used to run weekly in the Excelsior newspaper, written by agents from Gobernación and used by the regime to defend government policies. And then there are the records of an even dirtier war, which chronicle the state’s attempt to eliminate the radical left: army counterinsurgency plans; cables from Guerrero describing the hunt for guerrillas, the mass detentions of families of rebel leaders. Reports on interrogation sessions. Photographs of detainees with visible signs of torture. Photographs of dead people—some of their names appear on the list of the “disappeared” released by the National Human Rights Commission in 2001.[3]

The archives also contained a vast quantity of files on the movimiento estudiantil (student movement) of 1968 – the marches and protests and meetings and strikes that led, inexorably, to October 2 on the Plaza of the Three Cultures at Tlatelolco. Journalists, historians, human rights groups, scholars of 1968, and veterans of the student movement studied the files and turned out a remarkable number of new articles and books about Tlatelolco in the years following their release. It seemed that even if the government itself was not willing to admit responsibility for the human rights crimes committed by its agents, the people would be able to find their own truths in the enormous treasure trove of newly open information.

Alas, Mexico’s glasnost could not last. When the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) returned to power in 2012 with the election of President Enrique Peña Nieto, it brought its old, suffocating ways with it. Inside the AGN, a new director was appointed and through her the changes were mandated. Although Interior’s political intelligence files remained (and still are) open and unrestricted, the Secretariat of Defense (Sedena) collection closed altogether and the DFS records were radically altered. Where once there was virtually unlimited access to DFS intelligence reports about 1968 – mostly untouched and unexpurgated – now only heavily redacted “public versions” are available to researchers.

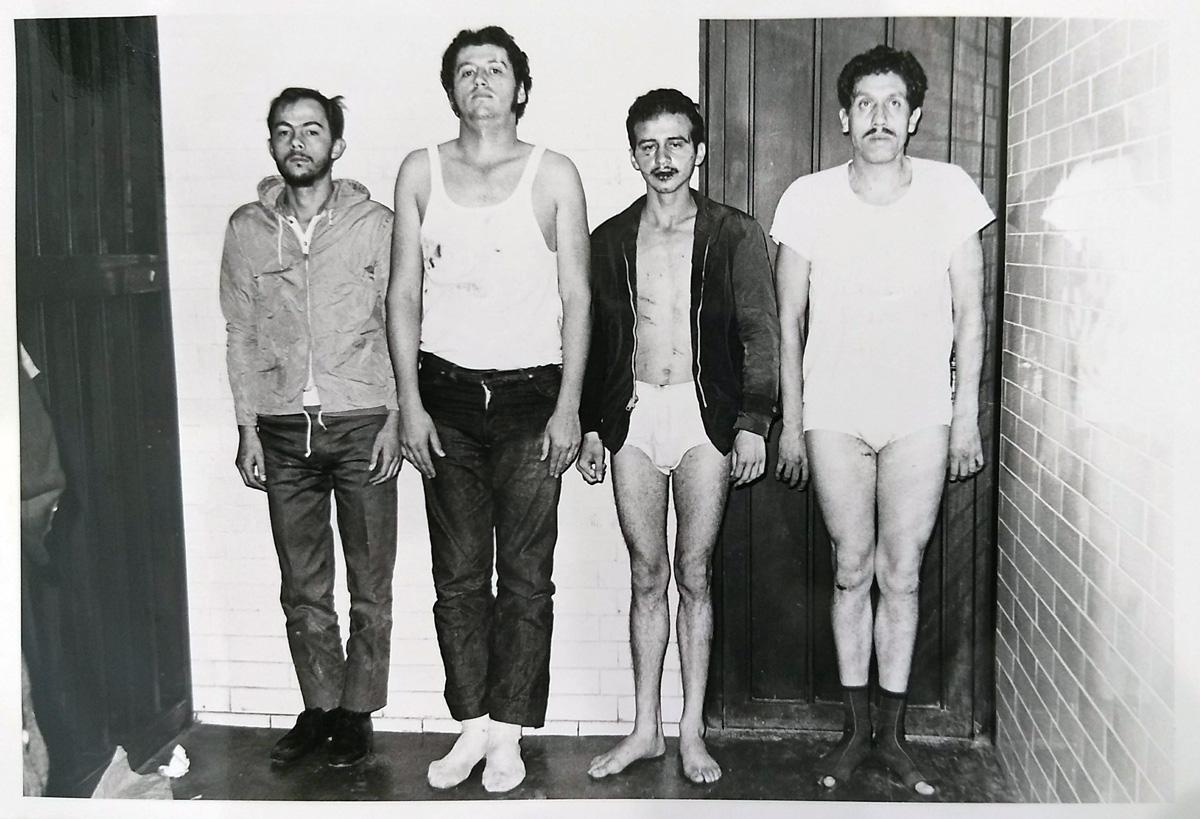

The post-censorship public versions are visual symbols of the irrationality of the AGN’s current policies about access. According to the AGN, the information deleted is protected for privacy reasons, as required by the 2012 Archives Law: “Sensitive personal data that affect the private life of the subject or whose abuse might give rise to discrimination or imply grave risk.”[4] Yet many of the records withdrawn or blacked out have not only long been available without restriction, they have appeared in books, magazines and newspaper stories, they are cached on-line at academic and research websites, and cited in countless articles. For example, a well-known photograph of students detained and beaten at the October 2 rally has appeared for years as an illustration of the brutality of the State security forces at Tlatelolco:

Detainees in Military Camp Number One, 3 October 1968

Credit: AGN archives, Dirección General de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociales, Caja 2911-A

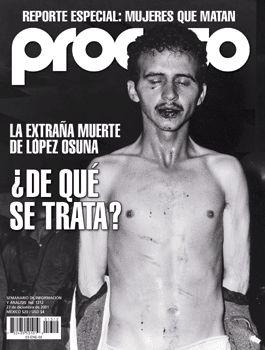

A version of it has been used on the cover of magazines:

Florencio López Osuna, 1968

Credit: Cover of Proceso magazine No. 1312, 23 December 2001

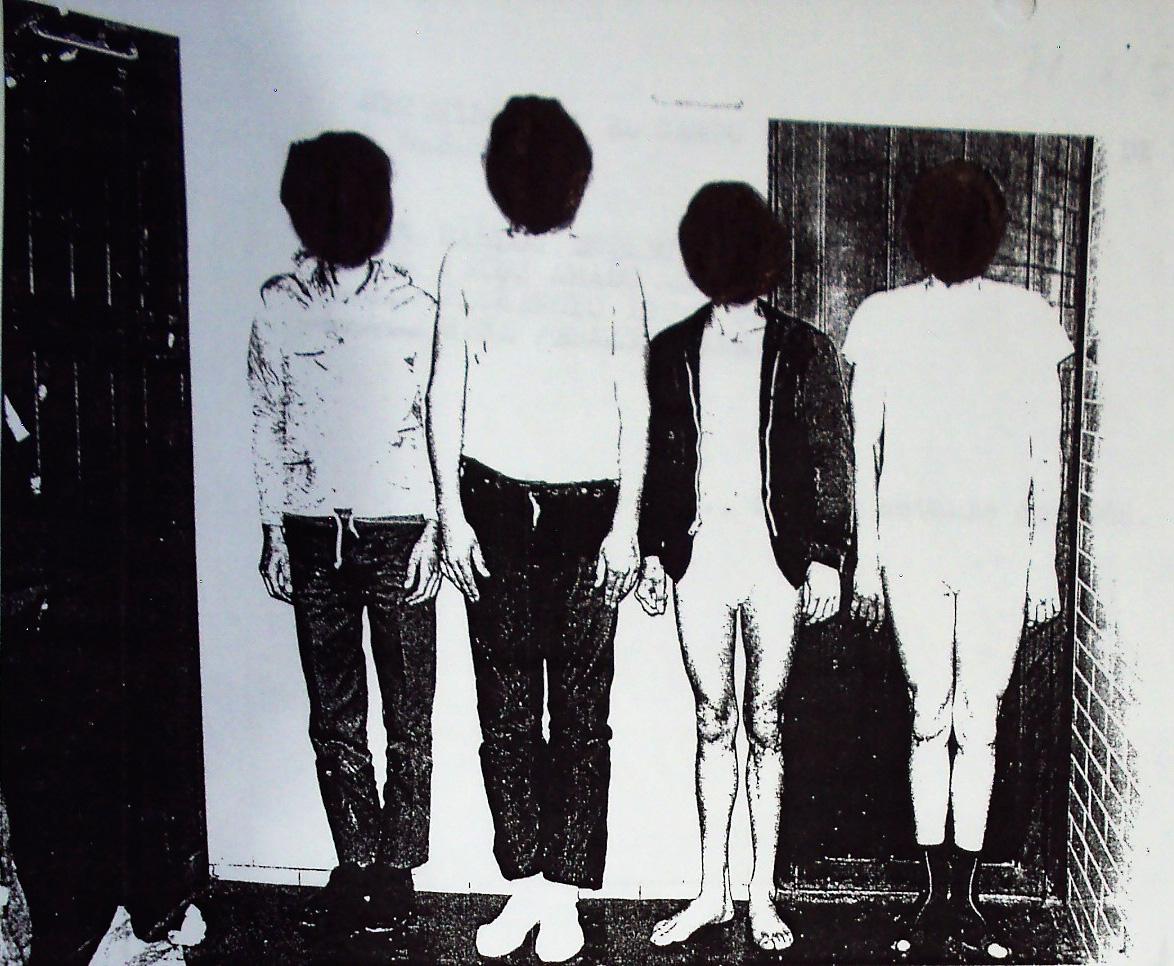

In the re-reviewed and re-classified files of the intelligence files of the DFS, the photograph is now available in two “public versions”:

Detainees in Military Camp Number One, 3 October 1968

Credit: AGN archives, Dirección Federal de Seguridad, Problema Estudiantil, Tomo 25 y 26

Detainees in Military Camp Number One, 3 October 1968

Credit: AGN archives, Dirección Federal de Seguridad, Problema Estudiantil, 2 al 4 de Octubre

It is hard to know what the current government hopes to achieve by reclassifying fifty-year-old records on past atrocities. In addition to the files noted above, there is a wealth of information about Mexico’s dirty war already in the public realm, not all of it from the Mexican national archives. Since 1998, for example, the National Security Archive at George Washington University has published hundreds of declassified US documents about Mexico’s 1968 student movement, beginning with our first posting in commemoration of the thirtieth anniversary in which we called for the opening of Mexican archives as the only antidote to secrecy and silence. Five years later, we posted more than one hundred US records from the CIA, Defense Intelligence Agency, US Embassy in Mexico and State Department about 1968 and Tlatelolco, offering a comprehensive look at what the United States knew about the massacre before and after it was carried out. And in 2006, we published an analysis of the dead of Tlatelolco, based on eight months of research in the AGN for records containing information about the massacre’s direct casualties.

In the wake of the AGN’s newly restrictive access policies, scholars of Mexico’s dirty war are pushing back. On September 13, a group of academics and researchers held a press conference in Mexico City to announce the launch of an ambitious digitization project aimed at making accessible thousands of records about the 1968 student movement and the years of violent state repression that followed. The transnational collaboration – dubbed “Mexican Intelligence Digital Archives” (MIDAS) in English and Los Archivos del Autoritarismo Mexicano in Spanish – is made possible by researchers who have spent years collecting and copying the dirty war files during the decade before they were withdrawn and re-classified.

Sergio Aguayo of El Colegio de México and our own Mexico Project at the National Security Archive are the pioneer participants in this collaboration, but many other scholars and historians are expected to join. The platform is hosted by the Center for Research Libraries (CRL), an international consortium of university, college and independent research libraries based in Chicago, Illinois. The National Security Archive’s special collection is drawn from documents we pulled and copied from the AGN in the early to mid-2000s.

Through the MIDAS project and other independent and innovative research efforts, Mexican scholars and the international research community will continue to challenge the Mexican government’s latest attempts at erasing the history of the Tlatelolco massacre. And by the time the fifty-first anniversary rolls around, a new government will have taken office, presenting a new opportunity for the Mexican public to insist that the State recognize its responsibility for the tragedy of October 2, 1968.

Notes

[1] See, for example, Sergio Aguayo’s most recent book on the student movement and the tragedy of Tlatelolco, Mexico 68: The students, the president and the CIA, (Mexico City: Gandhi Publica, September 2018). E-book available at Barnes & Noble on-line.

[2] The National Security Archive downloaded the report the day it was published. The Informe Histórico a la Sociedad Mexicana – 2006 now exists only on the Archive’s website.

[3]Kate Doyle, “Forgetting is not Justice: Mexico Bares its Secret Past,” World Policy Journal, Summer 2003, p. 71

[4] Translation of the relevant text in the Mexican Archives Law is from Andrew Paxman’s blog posting of 12 April 2015, “Crisis at Mexico’s National Archive: Arbitrary Censorship and Poor Leadership at the AGN.” Although slightly out of date now, Paxman’s narrative of how the dirty war archives became subject to a series of seemingly arbitrary restrictions imposed by the new AGN director, Mercedes de la Vega, is excellent and valuable.