Washington, D.C., December 6, 2016 – On November 9, 1983, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization launched a nuclear war against its nemesis, the Warsaw Pact, after NATO military commanders sought and received permission for “initial limited use of nuclear weapons” from the political leadership of the Western alliance. A detailed account of this horrific – if fictitious – conflict appears in a NATO scenario that is being published today by the National Security Archive and featured in the new book Able Archer 83: The Secret History of the NATO Exercise that Almost Triggered Nuclear War.

When “Blue’s” limited attack failed to stop “Orange” forces, NATO commanders proposed “follow on use of nuclear weapons” – essentially a carte blanche escalation – which they duly executed on the morning of November 11. Only then, with almost nothing left to destroy, did Able Archer 83, the NATO war game designed to practice the release of nuclear weapons during wartime conditions, come to an end.

While the 1983 nuclear conflagration was fictional, the top military and political leaders involved were entirely real, and the war game they enacted was based wholly on global strategic realities.

Now available to purchase, Able Archer 83, by the National Security Archive’s Nate Jones, tells the story of this dangerous but largely unknown nuclear exercise, the generals who ran it, and the American and Soviet leaders it affected, through a selection of declassified documents pried from U.S. and British agencies and archives, as well as formerly secret Soviet Politburo, KGB, and other Eastern Bloc files. The book vividly recreates what the U.S. government’s spy agency, the National Security Agency, described as “the most dangerous Soviet-American confrontation since the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

The book shows that Able Archer 83 simulated nuclear launch procedures so realistically that it triggered a Warsaw Pact response “unparalleled in scale” and risked actual nuclear war, in the words of a recently declassified, authoritative, all-source intelligence review included in Able Archer 83. This high-level review “strongly suggest[ed]” to its authors, the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, “that Soviet Military leaders may have been seriously concerned that the U.S. would use Able Archer 83 as a cover for launching a real attack” and that “some Soviet forces were preparing to pre-empt or counterattack a NATO strike launched under cover of Able Archer.”

For the National Security Archive's complete collection of over 1,000 declassified documents on the 1983 War Scare, see The Able Archer Sourcebook.

Able Archer 83 included “special wrinkles” that could have been misinterpreted by the Soviets, including testing new communications methods for nuclear release and the fact that "some US aircraft practiced the nuclear warhead handling procedures, including taxiing out of hangars carrying realistic-looking dummy warheads."

In response to possible indicators of a nuclear attack, the Warsaw Pact initiated an "unprecedented technical collection foray against Able Archer 83," including over 36 Soviet intelligence flights, significantly more than in previous exercises, conducted over the Norwegian, North, Baltic, and Barents Seas, "probably to determine whether US naval forces were deploying forward in support of Able Archer." Warsaw Pact military reactions to Able Archer 83 were also "unparalleled in scale" and included "transporting nuclear weapons from storage sites to delivery units by helicopter," and suspension of all flight operations except intelligence collection flights from 4 to 10 November, "probably to have available as many aircraft as possible for combat."

The all-source intelligence review concluded, "There is little doubt in our minds that the Soviets were genuinely worried by Able Archer" and that the U.S. intelligence community's erroneous reporting made the "especially grave error to assume that since we know the US is not going to start World War III, the next leaders of the Kremlin will also believe that."

Upon being apprised of this danger, President Reagan "expressed surprise" and "described the events as ‘really scary.'" He also learned from the danger of Able Archer 83 and the 1983 War Scare. In his memoir, Reagan wrote, “Three years had taught me something surprising about the Russians: Many people at the top of the Soviet hierarchy were genuinely afraid of America and Americans. Perhaps this shouldn’t have surprised me, but it did…I think many of us in my administration took it for granted that the Russians, like ourselves, considered it unthinkable that the United States would launch a first strike against them. But the more experience I had with the Soviet leaders and other heads of state who knew them, the more I began to realize that many Soviet officials feared us not only as adversaries but as potential aggressors who might hurl nuclear weapons at them in a first strike[.]”

Four years later, a Top Secret intelligence estimate, published today for the first time, confirmed Reagan’s fears, concluding that, “if they had convincing evidence of US intentions to launch its strategic forces…the Soviets would attempt to preempt.”

READ THE DOCUMENTS

Artist's rendition of a mobile SS-20 launch in the field. According to the National Security Agency's internal history, the NSA's overhead photography was only able to spot SS-20s during "an occasional lucky accident." U.S. National Archives.

Document 1: "Exercise Scenario," Undated, NATO Unclassified.

Source: Kindly provided by SHAPE chief historian Gregory Pedlow.

The unclassified summary of Exercise Able Archer 83 provided by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) describes how NATO envisioned and practiced nuclear war.

According to the account of the exercise, the impetus for nuclear war began in February 1983 with a change of leadership in the Kremlin. By March, the new fledging Soviet leadership was fighting proxy wars against the United States in the Middle East by providing political and military support to Iran, Syria, and South Yemen.

By June, conflict had spread from the Middle East to Europe. Due to its failing economy, the Soviet Union was unable to continue proving its usual levels of aid to its Eastern European satellites. But while the Eastern European economic situation worsened, its military preparedness improved. Warsaw Pact forces conducted frequent field training exercises, stockpiled equipment, and factories producing materiel went onto round-the-clock schedules.

Then, in August, nonaligned Yugoslavia shifted toward the West, formally requesting economic and military assistance from several NATO countries. Fearing Eastern European states could follow, the Warsaw Pact invaded Yugoslavia.

On October 31, the ground war broadened. Soviet Forces invaded Finland and, the next day, Norway. The Soviets commenced massive air and naval attacks against NATO’s European forces and bases. In southern Europe, Soviet ground forces invaded Greece while its navy carried out attacks in the Adriatic, Mediterranean, and Black Seas.

By November 4, Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces invaded West Germany while bombarding its entire eastern border with air attacks. Because NATO forces provided strong resistance to these Soviet invasions, conventional war turned unconventional. By November 6, Soviets forces launched chemical attacks, NATO responded in kind.

Unable to repel the Soviet’s ground advance, NATO attempted to send a message to the Warsaw Pact via nuclear signaling –the nuclear destruction of one city in the hope of averting total nuclear war. On the morning of November 8 NATO requested permission for “initial limited use of nuclear weapons against pre-selected fixed targets” on the morning of November 9. The Western capitals granted NATO permission to destroy Eastern European cities with nuclear attacks.

But “Blue’s use of nuclear weapons did not stop Orange’s aggression.” As a result, the next day the leader of NATO’s military, the Supreme Allied Command Europe (SACEUR), requested a “follow-on use of nuclear weapons.” Washington—and the other capitals—approved this request within twenty-four hours and on November 11 the follow-on attack was executed; a full-scale nuclear war had broken out.

A Pershing II is fired at White Sands Missile Test Range on November 19, 1982. U.S. National Archives.

Document 2: Extract from “The Soviet “War Scare,” President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, February 15, 1990, "TOP SECRET UMBRA GAMMA WNINTEL NOFORN NOCONTRACT ORCON."

Source: Mandatory Declassification Review Request to George H. W. Bush Presidential Library. Declassified by the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel.

This all-source intelligence review of the 1983 War Scare, released to the National Security Archive after a 12-year fight– concludes that the danger posed during Able Archer 83 was real.

"There is little doubt in our minds that the Soviets were genuinely worried by Able Archer… it appears that at least some Soviet forces were preparing to preempt or counterattack a NATO strike launched under cover of Abler Archer" and that "the President was given assessments of Soviet attitudes and actions that understated the risks to the United States." According to the PFIAB, the US Intelligence Community's erroneous reporting made the "especially grave error to assume that since we know the US is not going to start World War III, the next leaders of the Kremlin will also believe that."

"The Board is deeply disturbed by the US handling of the war scare, both at the time and since. In the early stages of the war scare period, when evidence was thin, little effort was made to examine the various possible Soviet motivations behind some very anomalous events… When written, the 1984 SNIE's [assessments] were overconfident." That estimate, written by veteran Soviet analyst Fritz Ermarth, downplayed the hazards.

Rather than shy away from discussing and analyzing the danger of nuclear war through miscalculation, the Board, chaired by Anne Armstrong, and the report's primary author, Nina Stewart, wrote that it hoped its "TOP SECRET UMBRA GAMMA WNINTEL NOFORN NOCONTRACT ORCON" report would prompt "renewed interest, vigorous dialogue, and rigorous analyses of the [War Scare]." – at least by the few cleared to read it!

Twenty-six years later, the public is finally privy to much of the information about the War Scare and can finally participate in “the renewed interest, vigorous dialogue, and rigorous analyses” recommended by the PFIAB.

Document 3: Talking Points for Meeting with Ambassador to the Soviet Union Arthur Hartman, March 28, 1984, Confidential.

Source: Reagan Presidential Library, Matlock files, Chron June 1984, Box 5.

The potential for war with the Soviet Union was frequently on President Reagan’s mind. Months after the War Scare, he met his Ambassador to the Soviet Union Arthur Hartman in the Oval Office. Reagan held two index cards with three questions printed on them during his meeting. The final one asked, "Do you think Soviet leaders really fear us, or is all the huffing and puffing just part of their propaganda?" and remains the most important question of the 1983 War Scare. In his diary, Reagan wrote, "Art Hartman came by. He's truly a fine Ambas. It was good to have a chance to pick his brains." But any answer that the ambassador gave to the president has not been found.

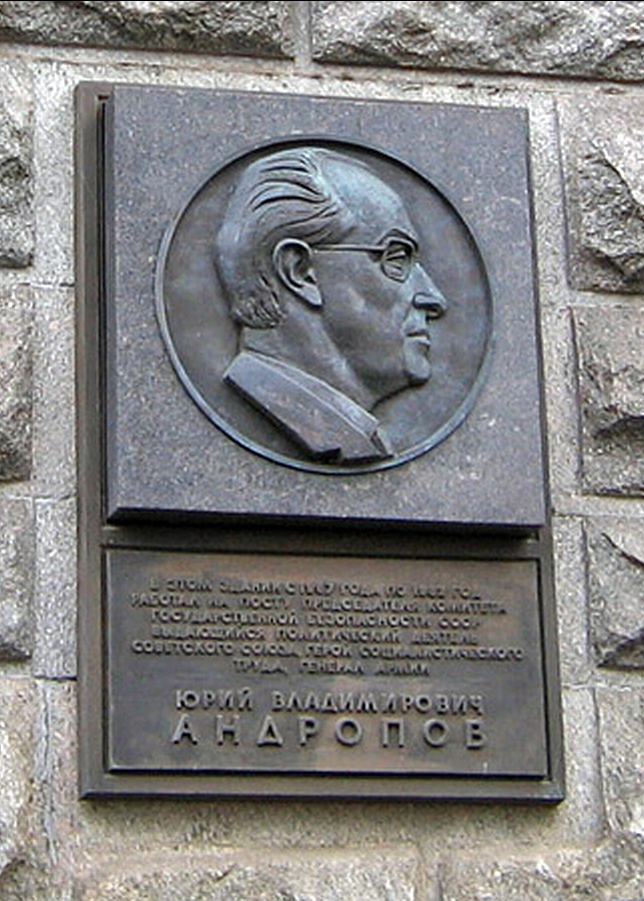

Plaque commemorating Yuri Andropov at Lubyanka, the headquarters of Russian State Security, dedicated by Vladimir Putin.

Document 4: Unpublished Interview with former Soviet Head of General Staff Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev, January 10, 1990.

Source: Princeton University, Mudd Manuscript Library, Don Oberdorfer Papers 1983-1990, Series 1, Soviet Interviews, 1990.

The great late Washington Post reporter Don Oberdorfer included a key footnote tipping the public off to the existence of the 1990 PFIAB report on the War Scare in his 1998 book From the Cold War to a New Era: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1983-1991. He also conducted an invaluable series of interviews with American and Soviet Cold Warriors once “on background” but now available to the public at Princeton University’s Mudd Manuscript Library. His interview with former head of the Soviet General Staff, Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev, is particularly enlightening.

In the key exchange of this 1990 interview, Akhromeyev tells Oberdorfer that he did not remember "Able Archer 83" but that "we believed the most dangerous military exercises are [were] Autumn Forge and Reforger. These are [were] the NATO exercise in Europe." Able Archer 83 was the nuclear climax to Autumn Forge 83. (Reforger was the radio silent deployment of some 19,000 US troops deployed to Europe for the war games.)

While Akhromeyev states that he felt no "immediate threat of war," he stated that “the Soviet leadership was gravely troubled by the state of Soviet-America relations” and that, "I must tell you that I personally and many of the people that I know had a different opinion of the United States in 1983 than I have today [1990]. I considered that the United States is [was] pressing for world supremacy … And I considered that as a result of this situation there can [could] be a war between the Soviet Union and the United States on the initiative of the United States."

Document 5: National Intelligence Estimate “Soviet Forces and Capabilities for Strategic Nuclear Conflict Through the Late 1990s,” Central Intelligence Agency, Top Secret.

Source: Mandatory Declassification Review Request to Central Intelligence Agency.

This CIA Intelligence Estimate, declassified after the National Security Archive spotted it in a footnote of the PFIAB, considers what would impact the Soviets’ “decision as to whether or not to risk initiating global nuclear war in various circumstances.”

According to the CIA, “If they [the Soviets] had convincing evidence of US intentions to launch its strategic forces (in, for example, and ongoing theater war in Europe) the Soviets would attempt to preempt” but, “[b]ecause preempting on the basis of such evidence could initiate global nuclear war unnecessarily, the Soviets would have to consider the probable nuclear devastation of their homeland…”

Nonetheless, “The Soviets have strong incentives to preempt in order to maximize theater damage to US forces and limit damage to Soviet forces and society.”

Over 400 pages in the annexes of this NIE were withheld in full by the CIA. According to the PFIAB report, there is a high likelihood that they discuss the risk or Soviet preemption by miscalculation, including an examination of the danger posed by Able Archer 83.

Of course, the National Security Archive has appealed these withholdings, and will continue to fight for their declassification.