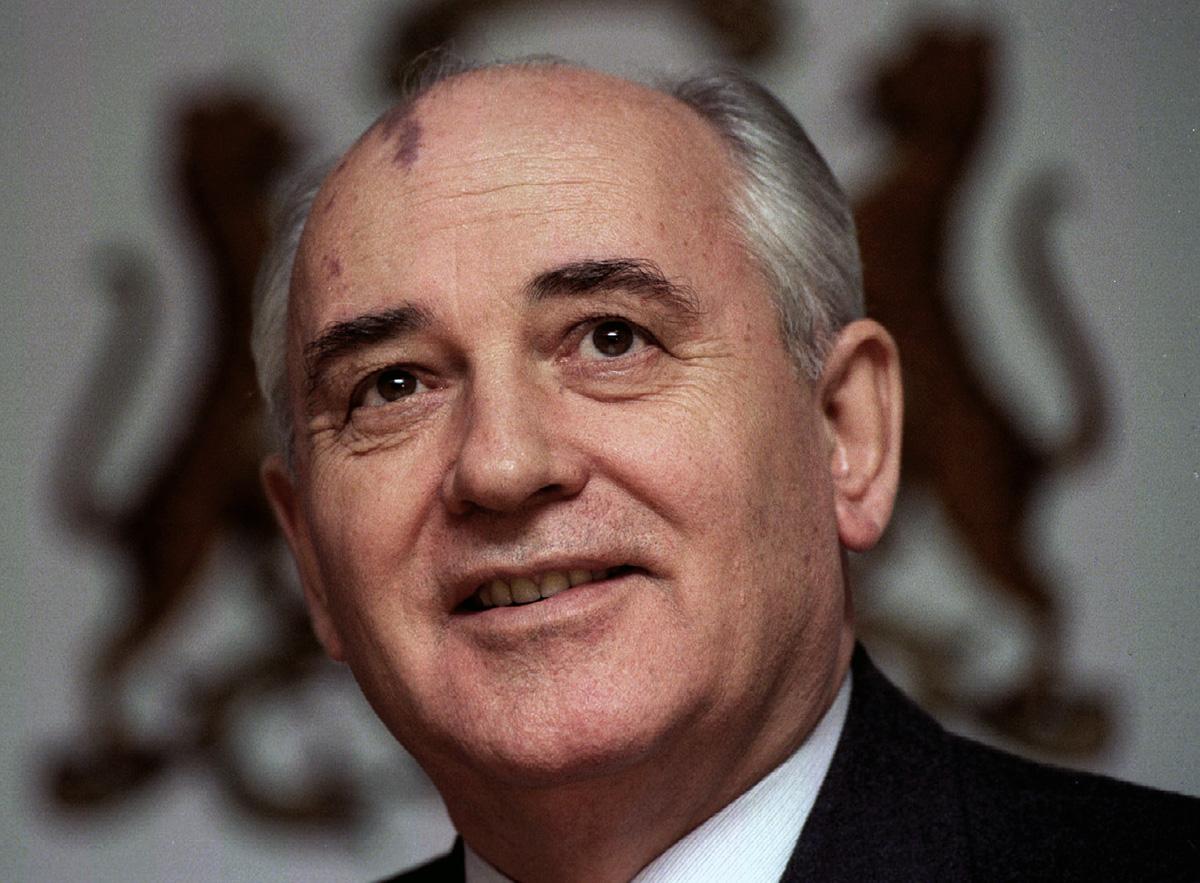

Washington, D.C., March 2, 2021 – The first and only president of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, is turning 90 years old today in Moscow. On the occasion of his anniversary, the National Security Archive has compiled a collection of postings called “Gorbachev’s Greatest Hits.” These documents help illuminate the story of the end of the Cold War, political reform of the Soviet system, and the vision of a world built on universal human values.

This compendium, accompanied by a collection of Russian-language documents on the Archive’s Russia Page, is intended to encourage scholars and others to revisit and study those miraculous years in the late 1980s and early 1990s when the global confrontation stopped, walls fell, peoples found freedom, and Europe was seen as a common home. Though not for long.

Gorbachev made history, and to a remarkable degree he also freed history from the usual constraints of security classifications and archival restrictions that often go on needlessly for decades. Only a year or two out of office, he had already started publishing the transcripts of his head-of-state meetings through the Gorbachev Foundation; and he liberated top aides like Anatoly Chernyaev to publish their memos and their diaries from which the international scholarly community has benefited enormously, and from which the National Security Archive has built dozens of Web postings, including the selections highlighted here, and published two award-winning books, Masterpieces of History and The Last Superpower Summits.

From the very beginning, Gorbachev engaged with U.S. and European leaders, believing that if only they met face-to-face and explained their beliefs to each other, they would no longer see each other as enemies. Gorbachev arguably saved Ronald Reagan’s presidency – without Gorbachev, Reagan would be remembered today mostly for the Iran-contra scandal and for selling the national debt to China. But in Geneva in 1985, Reagan met Gorbachev, and there the Soviet and the U.S. leaders proclaimed “nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”(EBB 172).

A year later in Reykjavik, Reagan and Gorbachev came very close to abolishing nuclear weapons altogether – a dream they shared. (EBB 203). No matter how one views Gorbachev’s policies, it is undeniable that no leader before or after him even came close to this achievement, all noble aspirations notwithstanding.

Breaking the Kremlin mold, Gorbachev went around the world, talking, persuading, and changing his own views along the way. He could hold a wide-ranging, passionate but respectful conversation with leaders as different as Margaret Thatcher, with whom he discussed revolutionary movements in the Third World (EBB 422), and Fidel Castro, with whom he conversed about U.S. politics (Document 1). The first and only Soviet leader to do so, he met with the Pope and found common ground as they deliberated over matters of peace and socialist choice (Document 8, EBB 298).

Gorbachev believed that together with his former opponents they could end all regional conflicts, starting with the war in Afghanistan. He announced the date for Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, and completed it exactly on that date – February 15, 1989, ending a bitter Soviet war that had gone on for almost ten years. Under his leadership, the Soviet Union cut military aid to third world dictatorships, even those who were considered “good” allies; he supported the United States in the Persian Gulf War even though his peaceful approach did not prevail. (EBB 745).

Of course he ran out of time. His domestic opponents – the hardliners in August 1991 seeking the old Soviet Union, and his “democratic” denunciator Boris Yeltsin afterwards, seeking his own power – brought Gorbachev down. Left behind were many global problems, not least the U.S.-Cuban confrontation that Gorbachev hoped to solve. He played behind-the-scenes mediator, telling George H. W. Bush he was mistaken about Castro, and telling Castro he needed to open to the U.S. Gorbachev passed messages between the two sides, but did not have time to complete the project.

Today the National Security Archive publishes three new memcons translated from the Russian, never posted before in any language, that reflect three important aspects of Gorbachev’s policy and aspirations. In his first trip to Cuba in 1989, Gorbachev spent long hours with Castro, whom he considered a legendary revolutionary leader but also hardheaded and mildly hostile to perestroika. Trying to explain perestroika to him, Gorbachev softly suggested that Cuba also needed to change and improve relations with the United States. (Document 1).

Meeting with Yitzhak Shamir of Israel, right before the beginning of the 1991 Madrid Conference on the Middle East, Gorbachev celebrated the new era he had just opened in Soviet-Israeli relations, re-establishing diplomatic ties, and aspiring to find a solution to the Palestinian issue within an international framework. (Document 2).

The last conversation published here is with Francois Mitterrand of France, right after the opening of the Madrid conference (Document 3). Gorbachev, on the high note of a successful start of the conference, was hoping to talk to Mitterrand about building the “common European home.” He believed the French leader shared his vision of Europe. There were many common features between the “European confederation” and “common European home” that the two leaders had discussed many times before. Now, however, after German unification in NATO, the war in the Gulf, and the August coup in the Soviet Union, the French leader wanted to talk about integration only on “his” side of the European continent.

Gorbachev did not have time to realize many of his ideas, chief among them the creation of a new voluntary and democratic and demilitarized Soviet Union. But the seven years he spent as leader of the Soviet Union changed the world to an extent nobody imagined before. Gorbachev, more than any other figure, ended the Cold War, then worked to ensure the story could be told.

Happy birthday, Mikhail Sergeyevich!

Read the documents

Document 1

Archive of Gorbachev Foundation, Fond 1, opis 1

Mikhail Gorbachev visits Cuba right after the first Soviet multicandidate elections in March 1989, which ushered in the era of increasingly free elections in the socialist bloc. His earlier planned trip to Havana in December 1988 had to be scrapped because of the earthquake in Armenia. Although Fidel Castro was critical of perestroika, the two leaders quickly found a common language based on deep mutual respect and commitment to the Soviet-Cuban relationship. Gorbachev tries to explain the ideas of perestroika to Castro and tactfully suggests that Cuba needs to change as well: “We are faced with the task of adapting socialism to the current realities, of opening [fully] the potential of our social order so that it reflects the imperatives of the time adequately.” Gorbachev talks about individual paths for individual socialist countries and his respect for their approaches.

A large part of the conversation focuses on U.S. politics and foreign policy. Gorbachev complains to Castro about George H.W. Bush’s “pause” and Castro calls that policy “sluggish.” Gorbachev sees the influence of the military-industrial complex behind Bush’s “vacillations.” Castro shares some astute observations about Reagan saying that the Iran-Contra scandal undermined his standing, and that he “would never have been able to achieve such popularity and respect in the international arena had he not signed the [INF] treaty with the Soviet Union.”

The main focus of the conversation is Latin America. Here, it is mainly Castro talking and Gorbachev listening. He notes the debt crisis, the new problem of narcotics, and narcobusiness serving the U.S. market.

Document 2

Archive of Gorbachev Foundation, Fond 1, opis 1, copy donated to the National Security Archive by Andrey S. Grachev

Gorbachev holds this historic meeting with Yitzhak Shamir on the eve of the opening of the Madrid Conference on the Middle East. The Soviet Union had just reestablished diplomatic relations with the Jewish state on October 18. Shamir thanks Gorbachev for his role in convening the conference and his efforts to improve relations with Israel. Gorbachev tells him about recent progress in the Soviet Union regarding the treatment of Jews—they are now allowed to emigrate to Israel, and there are “already 22 schools in Moscow where Jewish religion and culture are studied.” Gorbachev asserts that there is no anti-Semitism in the USSR now (an overstatement), and that even during the difficult changes “society is not susceptible to this disease.”

Shamir is very grateful but also very cautious, especially as it comes to the format of negotiations. Gorbachev and Secretary of State James Baker’s understanding was that after the opening ceremony, the first round of bilateral negotiations would be held in Madrid in the international framework. Shamir, however, wants bilateral negotiations to take place locally, in the Middle East.

Document 3

Archive of Gorbachev Foundation, Fond 1, opis 1, copy donated to the National Security Archive by Andrey S. Grachev

On his way back from the Madrid conference, Gorbachev stops at Francois Mitterrand’s country house in Latche. In the evening, the two leaders discuss their vision of Europe after the Cold War. From the very beginning of the conversation, Mitterrand makes it very clear that he is primarily concerned about “Europe on our side,” which for him is the “community of 12 states.” He is against expanding NATO functions, especially into those spheres that fall under the scope of the CSCE, and feels that NATO should keep to its original limited role. Gorbachev wants to talk about the pan-European process, the “two pillars” of it, which are the European Community and the new Soviet Union, but Mitterrand responds coldly that “one of the pillars has already been created. As for the other pillar, it is not known what is happening to it.” Gone are the days when he talked about European confederation. Mitterrand emphasizes that he is in favor of a strong, federally bound Soviet Union; he believes that Europe will take shape gradually. They switch to the discussion of foreign aid to the USSR and Soviet internal affairs. Raisa Gorbacheva intervenes to point out that the “nomenklatura bites,” describing the great resistance of the Soviet bureaucracy to Gorbachev’s reforms, which culminated in the coup of August 1991.