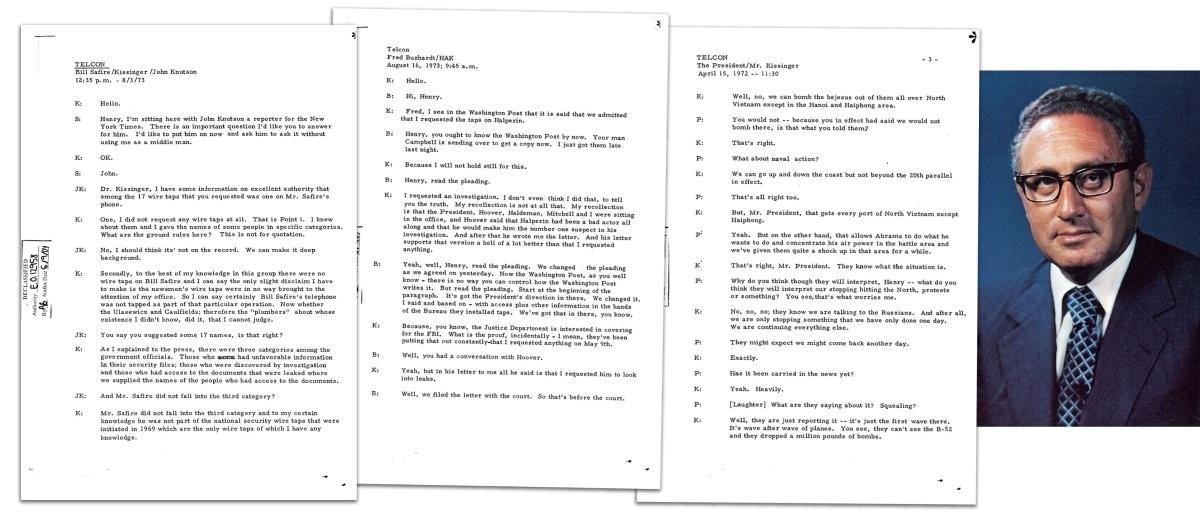

Washington, D.C., February 13, 2024 - State Department lawyers advised Henry Kissinger that transcriptions of his telephone conversations made when he served as national security adviser and Secretary of State were his personal papers and not “subject to disclosure under the FOIA,” according to recently declassified records from the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). When Freedom of Information Act requests, the possibility of lawsuits, and bad publicity complicated Kissinger’s ability to maintain control over these records, the lawyers suggested that he could stash the so-called “telcons” away in the Library of Congress. Kissinger’s subsequent decision to do precisely that put them out of reach of the FOIA for decades, until the National Security Archive forced NARA and the State Department to begin to recover more than 15,000 pages of telcons in 2001.

The newly declassified documents, which come mainly from the files of the State Department Legal Adviser, shed new light on decisions taken during the early stages of Kissinger’s effort to shield the telcons from public scrutiny.

When Henry Kissinger joined the Nixon administration as national security adviser in January 1969, he routinely had his telephone conversations transcribed for his office files. That continued when he became Secretary of State in September 1973.[1] For the most part, only a few White House and State Department insiders knew of this practice or that Kissinger had taken the collection of White House transcripts with him to State, under the watchful eye of Deputy Under Secretary Lawrence Eagleburger.

New York Times columnist William Safire broke the news about the telcons in a 14 January 1976 column and also sent a FOIA request to the State Department for telephone transcripts from 1969-1971 relating to White House-directed wiretapping operations aimed at suspected leakers. Safire, a former Nixon White House staffer, had been one of the targets of the secret bugging operation and wanted to know more about Kissinger’s decisions.

Safire’s FOIA request, soon denied by the State Department, was the first challenge to Kissinger’s exclusive control of the telcon transcripts, which he saw as his personal property, in part based on the counsel of the State Department Legal Adviser. Nevertheless, the collection included records of his conversations with many government officials, diplomats, and journalists relating to his work as a senior Nixon administration official. Recognizing the sensitivity of recording conversations without the consent of the other party, Kissinger tried to keep the transcripts secret as long as he could. By the end of 1976, journalists had learned more about the telcons. Media outcry and a threatened lawsuit by historians prompted Kissinger to quick action: he donated the documents to the Library of Congress where they would be out of reach of FOIA requests.

Most of the documents posted today come from the records of State Department Legal Adviser Monroe Leigh, who held that position during 1975-1977. To get access to the 17 cartons of Leigh’s records, the National Security Archive made an Indexing on Demand request to NARA’s National Declassification Center, which completed their final processing and opened them in November 2023.

Even as many important collections remain unavailable—Eagleburger’s official files are still held at State, while Kissinger’s papers remain closed—these new documents from the Leigh collection provide fascinating insights on Kissinger’s initial efforts to keep the telcons secret.

Background

The detailed records that Kissinger made of his thousands of telephone conversations with U.S. presidents, senior government officials, diplomats, and foreign leaders, not to mention with journalists and academics, are critically important for understanding U.S. national security policymaking during two Republican administrations. While Kissinger found the telcons useful for keeping track of day-to-day official interactions, when a reporter learned about the telcons in 1971, Kissinger denied that he had any plans to use them for an eventual memoir (although he would do exactly that).[2]

The documents published today demonstrate how Leigh advised Kissinger to claim that the telcon transcripts were not government records but rather his personal property. While NARA challenged that claim in early 1977, it was not until 2001 that the U.S. government took action to recover the telcons as federal records.

Under threat of legal action by the National Security Archive in 2001, NARA and the State Department asked Kissinger to provide copies of the missing telcons. Unwilling to challenge a decision made by the Republican administration of President George W. Bush and hoping to avoid negative publicity, Kissinger complied. Soon NARA and the State Department initiated declassification reviews, in part prompted by National Security Archive FOIA requests for the State Department transcripts. (Telcons held at the Nixon Library could only be requested through mandatory declassification reviews.) By 2004, thousands of the telcons had been declassified. During the decades that followed, thousands more became available, with more declassified after the Archive filed a lawsuit with the State Department for hundreds of telcons that had been denied.

Safire knew about the telcons when he was at the Nixon White House, and by the time he filed his FOIA request he could back it up with indisputable evidence that the State Department had them. Information about the existence of the records had become public through a lawsuit filed against Kissinger and Nixon filed by another wiretap target, Morton Halperin, who had been an aide to Kissinger in 1969. In response to an early interrogatory in that legal action, Kissinger declared in 1973 that as a “routine government practice” he had his secretaries monitor his phone conversations so they could prepare transcripts. He further acknowledged that the records were kept at the State Department. Safire’s FOIA was followed by a few others in 1976—from The Washington Star, The Washington Post and other papers—but at the time none of the journalists disclosed the requests or the State Department’s denials, perhaps for competitive journalistic reasons.

1976 was also an election year, and Kissinger began giving some thought to what he should do with his White House and State Department papers, in part because he wanted to access them later to write his memoirs. In detailed reports prepared during the spring of that year, Monroe Leigh reviewed Kissinger’s options, ranging from leaving the records at the Department of State to making a donation to the National Archives. There were pros and cons to each of these options, but whatever course Kissinger took, Leigh supported Kissinger’s view that the telcons were his personal papers [See Documents 11 and 14]. He understood there were downsides to that position, such as the possibility of litigation, but did not consider the possibility that the National Archives would want to weigh in on the matter or acknowledge that it had the authority to do so.

The complications raised by either keeping the records at State or transferring copies to NARA may have made Kissinger interested in alternatives when he met for lunch with Librarian of Congress Daniel J. Boorstin in August 1976. Boorstin proposed that Kissinger donate his records to the Library’s Manuscript Division, which was a repository for the records of many former U.S. Secretaries of State [See Document 17]. That offer became the focus of Kissinger’s attention once the election results were in. As the donation was being considered, Monroe Leigh’s deputy, Michael Sandler, stipulated that, because they were either personal papers or copies of agency records, “there should not be any basis for access under the Freedom of Information and Privacy Acts.” In any event, as a Congressional institution, the Library is immune from FOIA requests.

Even before the election, Kissinger took a significant step around 29 October 1976 by having the telcons secretly shipped back to Vice President Nelson Rockefeller’s estate in Tarrytown, New York. He had moved them there before, in 1973, with some later returned to the State Department. Consistent with this, when Kissinger donated his personal papers and copies of official papers to the Library, he excluded the telcons. That became publicly known on 21 December 1976, when The Washington Post’s Don Oberdorfer broke the story.[3] The revelation produced awkward questions at the State Department’s press briefing the following day, with reporters asking about the telcons, how they were prepared and used, and why Kissinger considered transcripts of his conversations with reporters or the Soviet ambassador to be his personal records.

Those circumstances and other problems persuaded Kissinger to change course. On 23 December 1976, Monroe Leigh warned Kissinger that the American Historical Association, represented by an Arnold & Porter attorney, would make Kissinger’s personal control of the telcons the subject of a lawsuit. [See Document 25] Litigation and ensuing court orders could have “very immediate consequences for your use of the telcons,” he advised, and a lawsuit would create more press attention. Leigh suggested that depositing the telcons at the Library of Congress could bring press speculation to an end and head off any litigation. The next day, Kissinger added the telcons to his deed of gift to the Library.

Leigh was overoptimistic about how the press would respond to the announcement of the second deed of gift on 28 December 1976, which noted that Kissinger wanted to prevent “misinterpretation,” prompting reporters to ask what, exactly, might be misinterpreted. Soon, Don Oberdorfer reported in The Washington Post on the secret storage of the telcons at the Rockefeller estate.[4]

The National Archives had an uneven record in persuading agencies to turn over records, but Archivist James Rhoads must have seen Kissinger’s well-publicized actions as a serious challenge. He tried to get access to the telcons so that archivists could determine whether they were government records, Nixon materials, or Kissinger’s personal papers. But it was too late. With the telcons now housed at the Library of Congress, Kissinger had effective control and declined the Archivist’s request. Kissinger’s denial was backed by a new legal opinion, also from Leigh, which found that the Archives should not have access to the telcons, in part because NARA was an “‘advocate’ of a restricted officials’ right to personal papers.” [See Document 32]

In February 1977, Rhoads renewed his request to Kissinger, now a private citizen, deploying strong legal arguments about the National Archives’ authority to inspect the telcons and determine their status. This time Kissinger relented a bit to the point of allowing the Archives to participate with the State Department in an inspection. Yet there was no meeting of the minds on which telcons were records and which of them were non-records [See Document 34]. The Archives asked Secretary of State Edmund Muskie to restart the inspection process and make its own appraisal. But when the State Department worked out a plan with the Justice Department to review the telcons, it excluded any role for the Archives. The National Archives, then a unit under the control of the General Services Administration, had no say in the matter.[5]

In the meantime, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, working with other organizations, filed FOIA requests to the State Department for the telcons and, after losing appeals, initiated litigation. The lawsuit was partly successful at the lower court levels, which ruled that the telcons from Kissinger’s tenure at the White House were immune from the FOIA but that the Library of Congress should return to the State Department the records from Kissinger’s time as Secretary of State. In 1980, the Supreme Court overturned those decisions, ruling that only agency heads, not private parties, had the authority to compel Kissinger to return the telcons. There the matter lay until the National Security Archive reopened the question in early 2001, promising litigation unless the National Archives and the State Department took action to compel Kissinger to return copies of the telcons from his years in office.[6]

Note: Thanks to Jonathan Garcia, George Washington University, for research assistance, and to David Langbart, U.S. National Archives, for his generous assistance with locating some of the documents used in this posting.

The Documents

I. Early Perspectives on the Telcons

Document 1

National Archives, Department of State Records, Record Group 59 (RG 59), Records of Monroe Leigh, box 2, Chronological File 1975 (January-April 1975)

This early look at the legal problems associated with producing and keeping records of telephone conversations never mentioned Henry Kissinger by name (it is presented as a “hypothetical case”), but whoever wrote the memorandum may have had some inside knowledge of the Secretary’s record keeping practices. The author found that transcripts of conversations produced using government resources and prepared in order to keep track of government business could not be claimed as personal property or be destroyed by the official who created them. According to the author, “Only if the transcripts were made and used exclusively by the government official himself would there be any chance of claiming they are personal property and even then success is uncertain.” If the documents were the subject of a FOIA request, the government could deny them under various exemptions, including (b)(1), relating to national security matters, and (b)(5), which shields records that are part of deliberative processes.

Document 2

Records of Monroe Leigh, box 11, Secretary’s Papers and Records File 1

A “memorandum of law” prepared a few months later looked more closely at the problem of protecting sensitive diplomatic information in the telephone conversation transcripts and the Nixon tapes. While Michael Sandler’s memorandum did not state as fact that Kissinger had a collection of telcons, it was the assumption. Considering that at least one senator, Lowell Weicker (R-CT), had asked about the telcons, one of the issues considered was, in a case where Congress sought access to the telcons, whether the State Department could invoke executive privilege to protect sensitive diplomatic information. Such a claim could be justified legally, although Sandler suggested there might be “practical reasons” for not doing so.

As for the vulnerability of the telcons to FOIA requests, there were “ticklish problems.” The telcons could be deemed agency records if they were generated and kept on the Department’s premises, but there also was the argument that they were “personal” papers. If the telcons included foreign policy information, if “persons other than the Secretary were permitted to read the records, or if the records helped the Secretary or others to make departmental policies or decisions, the records could well be viewed as those of an ‘agency.’” If, however, the Secretary “intended to keep the records for his personal use, if he limited access to himself, and if he segregated them into files marked ‘personal,’ than the materials should perhaps be viewed as ‘personal’ rather than ‘agency’ records,” according to Sandler.

If FOIA requests were ever made for the records, exemptions could be invoked to prevent disclosure, but that assumed that the telcons had “been properly classified.” Sandler suggested the possibility of a review and the imposition of classification categories when appropriate.

II. The Safire FOIA Request

Document 3

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Freedom of Information Act – Safire Request of January 14, 1976

Before William Safire’s FOIA request arrived, a reporter, possibly Safire, had raised questions about the telcons. Carlyle Maw, Under Secretary of State for Security Assistance, told Leigh that the reporter had asked by what authority Kissinger’s telcon records for the Nixon period could be removed from the White House. During the discussion between Leigh and Maw, the possibility was raised that they were the Secretary’s personal papers. But even if they were government records, Kissinger had legitimate interests in keeping them at the State Department to consult them for current work and for their future “literary interest.” In Leigh’s view, the telcons probably did not fall under the scope of the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act, but he acknowledged that the General Services Administration/National Archives could disagree and create complications. Concerning Kissinger’s refusal, in his deposition for the Morton Halperin lawsuit, to disclose information on conversations with third parties, Leigh saw the government’s support for Kissinger’s rejection as legitimate but also saw another reason: the “governmental interest in assuring the confidentiality of advice proffered to senior officials and others.”

Document 4

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Freedom of Information Act – Safire Request of January 14, 1976

According to this memorandum, common law and constitutional law required confidential status for Kissinger’s telcons. The documents were not subject to the Presidential Records and Materials Preservation Act because they were not controlled by White House record keeping procedures. Thus, they could be withheld under FOIA exemptions. Moreover, “confidentiality may be legally justified in the absence of a statute” because it is “implied by common law courts where the need for confidentiality overcomes the asserted interest in disclosure.”

Document 5

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Freedom of Information Act – Safire Request of January 14, 1976

William Safire’s FOIA request for Kissinger telcons created a flurry of internal deliberations and memorandum writing, beginning with a meeting of White House and State Department officials. The discussion touched on several issues, such as whether the telcons were under the scope of the Nixon Materials Act, whether they were Kissinger’s personal papers, which FOIA exemptions could preclude release of the telcons, and whether they could be considered “drafts.” All of those issues required further consideration. White House Counsel Philip Buchen requested that Lawrence Eagleburger prepare a memorandum describing the volume and the scope of the telcons.

As far as can be told, Safire did not publicize his FOIA request or its eventual denial, but on 15 January 1976, he published a New York Times column, “The Dead-Key Scrolls,” where he raised questions about the removal of the telcons from the National Security Council (NSC), the “authority” for that action, and the ownership of the telcons. Safire concluded his column by writing that Kissinger’s transfer of the telcons to the State Department exposed them to FOIA requests. “Citizens rush in where solons fear to tread.”[7]

Document 6

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Freedom of Information Act – Safire Request of January 14, 1976

Sandler provided a recap of the telcon references in the Kissinger interrogatories. He noted that, contrary to Safire’s column, there were no characterizations that any of the telcons were “verbatim” records.

Document 7

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Freedom of Information Act – Safire Request of January 14, 1976

This preliminary report on the issues raised by Safire’s request covered a range of issues, including the legality of taping telephone calls, possible legal restrictions on Kissinger’s transfer of the telcons to the State Department, and alternative responses to the FOIA request. Among the possibilities, all of which were discussed in some detail, were to claim that the telcons were Kissinger’s personal records, that they were non-agency records (and thus not subject to the FOIA), that FOIA exemptions could be used to deny access, and that telecons produced prior to 8 August 1974 could be treated as Nixon records. The problems raised by each alternative needed to be explored further. To do so, Maw and Leigh requested Kissinger to approve a ten-day extension for the reply to Safire.

Document 8

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Freedom of Information Act – Safire Request of January 14, 1976

Leigh relayed Eagleburger’s request that copies of all White House and State Department papers that Kissinger had either signed, approved, or issued be placed in a “secure and convenient” government repository. Leigh observed that the new emphasis on copies suggested that this was a “fallback from the assertion that the papers are personal papers.”

Document 9

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Freedom of Information Act – Safire Request of January 14, 1976

Responding to Philip Buchen’s request for details on the telcons, Eagleburger reported that there were about 20 file drawers of the material covering a variety of topics, including social engagements along with discussions with foreign diplomats, U.S. government officials, Presidents Nixon and Ford, journalists and editors, and academic associates. According to Eagleburger, a thorough assessment of the telcons “would require enormous labor on my part … more the job of a librarian.

Document 10

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Freedom of Information Act – Safire Request of January 14, 1976

This long legal memorandum covered the issues raised by FOIA requests for Kissinger’s telcons, including ownership of the transcripts, their status as “agency records,” possible exemptions to their release under presidential papers laws, statutory exemptions, national security exemptions, exemptions for “inter-agency or intra-agency memorandums,” and privacy issues. On the agency records issues, as far as the White House telcons were concerned, “there is a strong basis for maintaining that these transcripts are not ‘agency records’” because Kissinger was then a member of the President’s immediate staff, and his records would not have agency status.

Document 11

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 3, Chronological File, February 1976

Here Leigh reviewed recent developments surrounding the State Department’s denial of Safire’s FOIA request on the grounds that the telcons requested were not agency records because they were from the period when Kissinger was on Nixon’s staff. Another FOIA request had come in from a Washington Star reporter that was likely to be denied on the same grounds. For Leigh, the problem raised by the FOIAs were not legal, but “political,” because of the certainty that Safire and others will “sensationalize” the telcons and initiate legal proceedings challenging the denials, “which will further mobilize public attention.”

To “defuse unfounded suspicion” but also to protect “sensitive” foreign policy information and to safeguard Kissinger’s “right to access” and “privacy rights,” Leigh proposed steps to donate the telcons and possibly other records. If Kissinger kept the records as personal property, the public reaction could be “explosive” and action in court at “personal expense” might be necessary to protect such a claim.

Leigh suggested several possibilities, including the immediate donation of records to the National Archives (except for the most recent material) and donation of Kissinger’s records to the National Archives (or to “some repository under government control”) upon his retirement. Leigh reviewed the various complications and requirements involved in donating records to the Archives. While the Archives have a “first rate” reputation for maintaining the security of records, Leigh saw an “outside possibility” that a staffer “may not adhere to customary standards of confidentiality.”

Once Kissinger returned from his South America trip, Leigh proposed a meeting with Eagleburger to discuss the possibilities.

Document 12

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 11, Unlabeled file

The State Department’s Council on Declassification Policy informed William Safire that the Department had upheld the denial of his FOIA appeal. Maintaining that the telcons were not agency records in the first place, which precluded an appeal, the Department informed Safire that “we have employed the same procedures to your request as would be applicable to an appeal.” Even if the telcons were agency records, they would be denied under exemption (b)(5) because the “documents reveal the detailed mental processes of government officials, as well as portray some discussions of policy and decision alternatives.” The attached memorandum by Leigh detailed the legal grounds for denying Safire’s appeal.

Document 13

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Secretary’s Papers and Records File 2

With the publication of Robert Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s The Final Days in March 1976, more important facts about the telcons reached the public: for example, that at various points Kissinger had them removed from the White House and shipped to the Nelson Rockefeller estate at Pocantico Hills, New York. In a column on 12 April 1976, Safire raised that issue but added new morsels, such as the fact that Kissinger’s White House office had an “inner file” of sensitive records including not only the telcons but also memoranda of conversations with the President and diplomats such as Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, for which were no other copies existed.

The matter came up in the State Department’s briefing on 13 April and Michael Sandler brought two “striking” matters to Leigh’s attention: 1) that the Department acknowledged that transcripts had been produced from tape recordings, and 2) the lack of precision as to which of Kissinger’s “private papers” went to the Rockefeller estate (for example, whether they included the telcons). Sandler predicted that this matter could come up again.

III. What to Do with Kissinger’s Papers

Document 14

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 11, Unlabeled file

This is an expanded version of the memorandum that Leigh sent to Kissinger on 16 February that includes copious supporting material. Perhaps Leigh prepared it because Kissinger wanted a more exhaustive and comprehensive review of the alternatives concerning the telcons and his other government papers. Kissinger may have also wanted to know more about what predecessors, like Dean Rusk, had done with their telcon records. Leigh believed that it was legally arguable that the telcons were personal papers and “not subject to disclosure under the FOIA,” but that if Kissinger made such a claim he would face the risk of litigation at his own expense. Otherwise, the telcons could be treated as partly personal and partly official, which would raise administrative complications (e.g., in preparing summaries of the official material for inclusion in Kissinger’s State Department files).

Leigh reviewed the possibility of including the telcons in Kissinger’s records at State, as Dean Rusk had done, or donating the telcons to the National Archives and pointed out the pros and cons of each option. For example, with a donation to the Archives there was the possibility that some of them would be determined to be subject to the Presidential Materials Act or the risk of a future decision that the telcons were government records. For Kissinger’s files held by the Executive Secretariat, Leigh reviewed two basic options: 1) transfer of the files to an approved storage facility, but of copies only, not originals, or 2) leaving the files at the Department, while making arrangements for copies to be made for transfer to an approved facility upon the time of Kissinger’s retirement.

Document 15

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Secretary’s Papers and Records File 2

How Kissinger reacted to Leigh’s recommendations is unclear, but State Department officials continued to look into procedures for inventorying and storing records and for granting access to former officials. This paper provided considerable detail on those matters.

Document 16

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Secretary’s Papers and Records File 2

Following up on his memorandum from 11 May, Monroe Leigh drafted a paper for Kissinger on “Disposition of Your Papers and Records.” The draft discussed the various records involved, including official State Department “working files” and the telcon records, with proposals for screening out the “working files” to remove any personal materials and arrangements for preserving them, not only to ensure Kissinger’s future access but also for their eventual transfer to the National Archives.

The chief Records Manager, John S. Pruden, commented on the draft, noting ambiguities on the record status of the telcons and the problems involved in describing Kissinger’s records as “working files,” with the implication that the files would have non-records status and would not be subject to the FOIA. Not entirely comfortable with that implication, Pruden suggested that any such arrangements for such a “controversial collection” could be “tested in court with the possible result of some form of access.” Whether Leigh worked up this memorandum further is unclear, but soon Kissinger had in mind the possibility of an arrangement with the Library of Congress, which Librarian Daniel J. Boorstin proposed in August 1976 [See Document 14].

IV. Final Decisions and Developments

Document 17

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 9, HAK Papers

Before Gerald Ford’s electoral defeat on 4 November 1976, Kissinger spirited away the telcons from the State Department. Believing that they were his personal property, regardless of the litigation risk that Leigh had mentioned, on 29 October he sent them back again secretly to Nelson Rockefeller’s estate, possibly without consulting State Department records managers, much less the National Archives.[8]

Ford’s defeat subsequently prompted Kissinger to make final decisions on arrangements for his papers. The uncertainties that Leigh had mentioned may have excluded from serious consideration storing records or copies at the National Archives or the State Department. A donation of personal and official papers to the Library of Congress, where Kissinger could have easy access, quickly became the focus of attention. There were uncertainties, however, and this report by one of Leigh’s aides looked closely at the legal and other questions involved in a donation, such as gift authority, possible claims of access by Congress or the Justice Department, the need for State and NSC approval, conditions of access, amenities for Kissinger (workspace, research assistance), the need for private counsel, because this was a private transaction between Kissinger and the Library, and the tenure of the Librarian of Congress.

Each of those topics raised questions that needed answers. For example, a key issue was access. Sandler asked whether it was reasonable to require that outside access be barred for 25 years or until Kissinger died (whichever was later), whether the Library’s employees would have access to the papers, and how the Library handle FOIA requests. Before he raised the latter question, Sandler had written that, “There should not be any basis for access under the Freedom of Information and Privacy Acts.” That was so, he opined, because the proposed donation did not consist of “agency records,” either because they were personal papers or copies of government records. Apparently, Sandler had not yet realized that Congress and its institutions were immune from FOIA requests.

Document 18

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, Box 11, HAK Papers

Some of Sandler’s questions about the Library of Congress may have been answered during a telephone conversation with John Broderick, the Manuscript Division’s chief. Broderick could not give Kissinger’s papers ironclad protection from Congressional requests, but, as he suggested, it had been decades since a subpoena had been served (for Robert Lansing’s papers from World War I). Whatever else Broderick and others with the Library had said, the answers must have been good enough, because the next day, on 12 November, Kissinger signed a donation agreement with the Library of Congress.

Document 19

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Secretary’s Papers and Records File 2

Apparently not knowing of Kissinger’s preemptive action on the telcons, Monroe Leigh provided him with a recap of the view that he had taken since the Department responded to Safire’s FOIA: that the telcon transcripts were not agency records but were personal papers. Leigh argued that they were personal because they were “retained solely at your discretion as work aids to help you recall prior conversations and events.” Leigh noted that he had reviewed some of the telcons and did not believe that their contents included “any government decisions or policy actions.” But if other telcons did include such information, he cautioned, Kissinger should review them and arrange to have an extract or summary prepared for preservation by records officials.

According to Leigh, “The fact that the papers were retained for personal use, that they were not required to be prepared, that they have been consistently treated as personal, and that they contained personal and private matter, support the view that they are personal in nature.” Leigh further observed that the fact that the telcon transcripts were prepared by government secretaries using government resources was not “controlling” because it was “accepted practice that officials who must devote extraordinary amounts of time to government duties may make use of government resources to prepare private correspondence and other personal materials.” He did not consider the possibility that the GSA/National Archives might not agree.

The State Department shared this memorandum with the media on 22 December 1976 when journalists learned that the telcons were not covered in Kissinger’s donation to the Library of Congress [see Document 25].

Document 20

National Archives, Research Services Staff Reference Files

With Gerald Ford losing the election to Jimmy Carter, the press had questions for briefer Robert Funseth about the status of pending negotiations, including the SALT talks, but also about transition arrangements at the Department of State. One journalist asked about arrangements for Kissinger’s records, “whether the monitored telephone conversations, for instance, belong to him or belong to the people.” He further stated that “we’re entitled to be told what papers will remain Government property and which will be sold or used in his personal pursuits.” When one of the journalists observed that keeping records of the telephone conversations was a “rather new procedure,” Funseth observed that keeping such records was a “rather customary practice, both in Government and in private life.” He informed the press, not quite correctly, that in January 1976, the Legal Adviser “ruled ... that secretarial notes of the Secretary’s telephone conversation are personal papers.” On this point, there were no follow-up questions except about the name of the Legal Adviser.

Other questions followed about the records of Kissinger’s meeting with Chinese and other foreign officials, with Funseth noting that even if there was not a U.S. interpreter present, there was a U.S. notetaker and records of the meeting had been preserved. In accordance with 1967 State Department regulations, Funseth explained, Kissinger would have copies of his official records, but they “will be kept in a Government facility so that the classified documents are properly secured.” He may not have known about the Library of Congress arrangement that had just been negotiated.

Document 21

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 3, Chronological File, December 1976

Leigh prepared talking points for Kissinger to use when meeting with President Ford to discuss his plans for donating copies of NSC and State Department documents to the Library of Congress. Leigh included a copy of a recent Philip Buchen memorandum on “Presidential Papers” that stipulated that “personal files do not include any copies, drafts, or working papers that relate to official business.” Leigh observed that a “question may arise as to whether this statement may be extended to some of your telephone memoranda.” He also saw a “problem” with a paragraph prohibiting the retention of copies of documents that include advice to the President, a requirement that “might cast a cloud” on the copies of White House papers that Kissinger was sending to the Library of Congress.

Document 22

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 3, Chronological File, December 1976

On 15 November 1976, U.S. Archivist James B. Rhoads issued a bulletin through the General Services Administration to heads of federal agencies concerning the “disposition of personal papers and official records.” A noteworthy point with direct relevance to the Kissinger telcons was the discussion of personal papers, which were defined as “papers of a private or nonofficial character which pertain only to an individual’s personal affairs that are kept in the office of a Federal official.” Such records, he said, should “be clearly designated by him as nonofficial and will at all times be filed separately from the official records of his office.”

In his cover memorandum, Leigh disagreed with the Archivist’s definition of personal records, seeing it as too restrictive. Existing law and federal regulations, he argued, “recognize that personal papers can include discussion of government activities.” He also saw a contradiction between the Archivist’s definition of personal papers and a requirement that “extracts be made of certain matters pertaining to official business that appear in ‘private-personal correspondence.’” Leigh did not mention the Kissinger telcons but he probably had them in mind.

Document 23

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 11, HAK Papers

Kissinger met with President Ford and discussed with him his wish to donate his “public papers” to the Library of Congress. The donation would include copies of his NSC and State Department records. “The President agreed with this procedure,” according to this record of their meeting.

Document 24

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 11, HAK Papers

Writing to Boorstin, Scowcroft sent him a transfer agreement for copies of papers from Kissinger’s NSC files. He enclosed a copy of the agreement with the Library for copies of Kissinger’s State Department files.

Document 25

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Secretary’s Papers and Records File 2

If Kissinger thought that sequestering the telcons at Rockefeller’s estate would end the matter, he found out otherwise. His Library of Congress donation became a news story on 21 December 1976 with the Washington Post’s Don Oberdorfer reporting that the donation would not include the telcon transcripts because they were “personal” records. According to the Post, when asked about the whereabouts of the telcons, Lawrence Eagleburger declared that “we haven’t faced the question of where” they would be kept, keeping secret Kissinger’s earlier action.

The telcons were also the subject of awkward questions at the Department’s press briefing on 22 December, with reporters asking about the telcons, how they were prepared and used, and why Kissinger considered transcripts of his conversations with journalists or the Soviet ambassador to be his personal records.[9] When asked whether the telcons would go to an archive or remain at the State Department, the answer was no, that “they belong to the Secretary.” When asked whether Secretaries Rusk or Rogers had such transcripts prepared and what had happened with them, the briefer said that “you will have to ask” the former secretaries. The briefer agreed to provide copies of Leigh’s 11 November legal opinion.

Leigh brought the press coverage to Kissinger’s attention the next day, further noting that the American Historical Association, represented by an Arnold & Porter attorney, would make Kissinger’ personal control of the telcons the subject of a lawsuit. Leigh noted that a lawsuit and ensuing court orders could have “very immediate consequences for your use of the telcons” and that a lawsuit would create more press attention. By contrast, depositing the telcons at the Library of Congress could help end press speculation and stop any AHA litigation.

Leigh proposed alternatives, with pros and cons, that he and Eagleburger could discuss with Kissinger: 1) a separate donation to the Library of Congress with the 25 year/Kissinger’s death restriction with privacy conditions for future disclosure of telcons, 2) a separate donation with a 35-year restriction, 3) include the telcons in the original deed of gift to the Library, 4) maintain the “current position” (personal records).

Document 26

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 11, HAK Papers

Apparently accepting Leigh’s advice and not wanting to leave the State Department under a cloud, Kissinger quickly arranged for a second deed of gift to donate the telcons to the Library of Congress.

Document 27

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, HAK Library of Congress Press Guidance and Clippings

At this State Department press briefing reporters continued to ask about the telcons, for example, about the GSA/National Archives Bulletin defining personal papers. A reporter asked how the State Department squared the Archive’s definition with “with the idea that Secretary Kissinger can treat as his personal property” transcripts that cover official matters. The spokesperson John H. Trattner had no answer and, when pressed, said he would look into it. The reporter persisted by asking about a departmental regulation that required the preparation of extracts or summaries from private papers that discuss official business, asking whether that was being done with the telephone call transcripts. The spokesperson said that would also be looked into.

Document 28

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 11, unlabeled file

At the beginning of the State Department’s news briefing on 28 December, spokesperson John H. Trattner announced that Kissinger had donated the telcon records to the Library of Congress. According to the Department’s statement, the telcons were prepared as “memory aids,” were not “action documents,” and were never circulated. Kissinger was adding them to the donation of his papers because he wanted to “avoid any misinterpretation.”

The reporters raised more questions, asking whether the recent memorandum from the Archivist influenced the decision, how many telcons there were, and why Kissinger had change his mind in view of the legal opinion that the telcons were “private papers,” and what, exactly, was the “misinterpretation” that the former secretary wanted to avoid. There were other “unanswered questions.” Trattner claimed that Kissinger had time to consider the privacy issue and that it had influenced his donation, including the stipulation about the consent of the “first party” in the telcon records.

Document 29

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 11, unlabeled file

This is the official statement on Kissinger’s second deed of gift, along with a copy of the deed, which was distributed at the December 28 press briefing. On the preparation of telcon extracts, they would be created only for matters that were not documented “in existing government records.” The State Department disagreed with the GSA/Bulletin on the grounds that it was “inconsistent with Department regulations that have been in effect since 1967.”

Document 30

RG 59, Access to Archival Databases Collection of State Department telegrams, 1976

The Department sent Kissinger guidance on the various issues that had come up, such as the Archivist’s bulletin and the matter of preparing extracts, among other issues. The answers would be provided only if asked.

Document 31

RG 59, Records of Monroe Leigh, box 15, Secretary’s Papers and Records File 2

Einhorn confirmed the receipt of Kissinger’s papers, including the telcons, on 14, 28, and 29 December 1976.

V. The National Archive’s Unsuccessful Intervention

Document 32

RG 59, Department of State P-Reel Printouts 1977, box 11

With the telcons and related matters in the news, the Archivist intervened. He informed Kissinger that, as Archivist of the U.S., he had responsibility for “ascertaining that Federal agencies create, maintain, and dispose of their records in an efficient and lawful manner, and that they preserve records of permanent historical value for eventual deposit in the national archival system.” Rhoads also stated that the Nixon materials preservation act made him “responsible for assuming custody and control of the Presidential historical records of the Nixon administration.” Consistent with that, he asked that professional archivists be allowed to inspect the telcons and related materials at the Library of Congress and determine whether “such material [is] indeed, personal property or whether some portions of them maybe Federal records or Nixon historical materials.”

For all intents and purposes, Kissinger denied Rhoads’ request by sending him a copy of a new Leigh memorandum that insisted that archivists had no useful role to play when the Department had decided that the telcons were personal papers. Leigh argued that the GSA was a “proponent for a definition of official records that is inconsistent with Department of State regulations.” Treating the Archives as an “advocate,” Leigh observed that “it would not seem appropriate for GSA archivists to preempt the Department of State by reviewing the notes in question.” Leigh also saw the Archivists’ request as prejudicial to the Department’s interests: the “respect for privacy expectations implicit in the Department’s regulations has enabled numerous Department officials to originate candid diaries and notes which have proved to be invaluable historical resources.”

Document 33

RG 59, Department of State P-Reel Printouts 1977, box 24

When Rhoads replied to Kissinger he put new Secretary of State Cyrus Vance in the loop by forwarding the letter along with the GSA’s legal opinion. Restating his request for professional archivists to determine the status of the telcons, Rhoads advised Kissinger that he had made the request because he had “authority and responsibility to make an independent determination of the character … of the telephone transcripts and related documents.” Reviewing the issues in detail, including statutory authorities and the protection of personal and private information, Donald Young’s legal opinion found a “glaring oversight” in Leigh’s memorandum: it “totally ignores any examination of the statutory and regulatory authorities and responsibilities” of the GSA as “delegated to the Archivist of the United States, which flow from the FRA and Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act.”

Contrary to Leigh’s view about agency freedom of action in determining the definition and preservation of federal records, Young maintained that the U.S. Code made “it quite clear that every agency head shall operate the agency’s records management program in full cooperation with and under regulations prescribed by the GSA.” He found Leigh’s rejection of a GSA role in the matter, because of a supposedly “disqualifying advocate’s interest in the ultimate resolution of the controversy,” as “patently absurd” because the Archivist based his request on “statutory authorities and responsibilities.” As for the status of Kissinger’s telcons, Young observed that the existence of “gray areas” between federal records and personal papers presented a strong argument “for the input of professional archivists in the decision-making process” concerning the status of the telcon transcripts.

Document 34

National Archives, Research Services Staff Reference Files

Perhaps the force of NARA’s legal arguments persuaded private citizen Kissinger to backtrack a bit, at least to the extent of agreeing to a NARA role, but it did not convince him to agree to the independent inspection that Rhoads sought. Instead, Kissinger accepted a plan for a joint inspection of selected telcons by NARA and the State Department officials.

NARA archivist Richard Jacobs, and State Department records manager John Pruden inspected over 500 telcons but were far from a meeting of minds on which were government records and which were not. As this tally summary indicates, Jacobs found that 88 percent of them were records, while Pruden believed that 51 percent were records. The joint review ground to a halt, and within months the State Department and the Justice Department developed a plan to exclude the Archives from a further role. As Milton Gustafson explained in his review of the story (see Appendix), the government would take no action to recover the Kissinger telcons to either the State Department or the National Archives.

Appendix

National Archives, Research Services Staff Reference Files

When the National Archives had a Diplomatic Branch with a large staff, the late Milton O. Gustafson was one of its chiefs, and he was a font of knowledge. With this paper from 1981, Gustafson provided a detailed review of the role of the Library of Congress in housing the papers of Secretaries of State and of the early controversies surrounding the Kissinger telcons, including Kissinger’s donation to the Library in 1976, the National Archives’ early attempt to get access to the telcon collection, and the lawsuit by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. As he noted, the Supreme Court ruling in the Reporters Committee lawsuit “implicitly invited agency action to recover the documents,” but it would take two more decades before that became possible.

Notes

[1] Kissinger served concurrently as national security adviser and Secretary of State from 22 September 1973 until 3 November 1975, after which he continued as Secretary of State until the end of the Ford administration (20 January 1977).

[2] Dorothy McCardle, “Kissinger: No Book,” Washington Post, 22 February 1971. See Walter Isaacson, Kissinger: A Biography (New York: Simon & Shuster, 1992) at pages 230-232, for some of the early history of the telcons.

[3] Don Oberdorfer, “Kissinger Giving Papers to Library of Congress,” Washington Post, 21 December 1976.

[4] Don Oberdorfer, “Kissinger Telephone Notes Were Kept at Rockefeller Estate,” Washington Post, 30 December 1976.

[5] For the story in detail, see Document 35, Milton Gustafson, “The Records of Henry Kissinger and Other Secretaries of State: Some Archival and Legal Anomalies,” Presentation at Session 78, The American Historical Association, Ninety Sixth Annual Meeting, Los Angeles CA, 28-30 December 1981.

[6] For details, see Gustafson, “The Records of Henry Kissinger.”

[7] William Safire, “The Dead-Key Scrolls,” The New York Times, 15 January 1976.

[8] Gustafson, “Records of Henry Kissinger.”

[9] Ibid., 4.