Washington, D.C., November 26, 2025 - On General Augusto Pinochet’s 60th birthday, November 25, 1975, four delegations of Southern Cone secret police chieftains gathered in Santiago, Chile, at the invitation of the Chilean intelligence service, DINA. Their meeting—held at the War College building on la Alameda, Santiago’s downtown thoroughfare—was called “to establish something similar to INTERPOL,” according to the confidential meeting agenda, “but dedicated to Subversion.” During the three-day meeting, the military officials from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay agreed to form “a system of collaboration” to identify, track, capture and eliminate leftist opponents of their regimes. As the conference concluded on November 28, a member of the Uruguayan delegation rose to toast the Chileans for convening the meeting and proposed naming the new organization after the host country’s national bird, the condor. According to secret minutes of the meeting, there was “unanimous approval.”

Chilean records refer to Condor as “Sistema Condor.” CIA intelligence reports called it Operation Condor. It was, as John Dinges writes in his comprehensive history, The Condor Years, an agency of “cross-border repression, [whose] teams went far beyond the frontiers of the member countries to launch assassination missions and other criminal operations in the United States, Mexico and Europe.” His investigation documented 654 victims of kidnapping, torture and disappearance during Condor’s active operational period in the Southern Cone between 1976 and 1980. A subdivision of Condor codenamed “Teseo”—for Theseus, the heroic warrior king of Greek mythology—established an international death squad unit based in Buenos Aires that launched 21 operations in Europe and elsewhere against opponents of the military regimes.

On the 50th anniversary of the secret inauguration of Operation Condor, the National Security Archive is posting a selection of documents that record the dark history of transnational repression under the Condor system. The selected records include:

- The only known DINA document on the inaugural meeting—the “Closing Statement of the First Inter-American Meeting of National Intelligence”—which summarized the agreement between the original five Condor nations.

- The first declassified CIA document to name “CONDOR” as a “cooperative arrangement” against subversion. The heavily censored CIA document, dated June 25, 1976, provides initial intelligence on the 2nd Condor meeting held from May 31 to June 2 in Santiago. It was the first in a flurry of CIA intelligence cables in the summer of 1976 on Condor’s evolution from an intelligence sharing collaboration to a transnational system of disappearance and assassination. “The subjects covered at the [2nd] meeting,” this CIA report noted, “were more sweeping than just the exchange of information on terrorism and subversion.”

- A CIA translation of the “Teseo” agreement—an extraordinary document that bureaucratically records the procedures, budgets, working hours, and operational rules for selecting, organizing and dispatching death squads to eliminate targeted enemies of the Southern Cone regimes. The “Teseo” operations base would be located “at Condor 1 (Argentina).” Each member country was expected to donate $10,000 to offset operational costs, and dues of $200 would be paid “prior to the 30th of each month” for maintenance expenses of the operations center. Expenses for agents on assassination missions abroad were estimated at $3,500 per person for ten days “with an additional $1000 first time out for clothing allowance.”

- A CIA report on how the Teseo unit will select targets “to liquidate” in Europe and who will know about these missions. The source of the CIA intelligence suggests that “in Chile, for instance, Juan Manuel Contreras Sepulveda, chief of the Directorate of National Intelligence (DINA) the man who originated the entire Condor concept and has been the catalyst in bringing it into being, will coordinate details and target lists with Chilean President Augusto Pinochet Ugarte.”

- The first briefing paper for Secretary of State Henry Kissinger alerting him to the existence of Operation Condor and the political ramifications for the United States. In a lengthy August 3, 1973, report from his deputy Harry Shlaudeman, Kissinger is informed that the security forces of the Southern Cone “have established Operation Condor to find and kill terrorists…in their own countries and in Europe. Brazil is cooperating short of murder operations."

- CIA memoranda, written by the chief of the Western Hemisphere division, Ray Warren, sounding the alarm on Condor’s planned missions in Europe, and expressing concern that the CIA will be blamed for Condor’s assassinations abroad. One memo indicates that the CIA has taken steps to preempt the missions by alerting French counterparts that Condor operatives planned to murder specific individuals living in Paris.

- The completely unredacted FBI “Chilbom” report, written by FBI attaché Robert Scherrer one week after the car bomb assassination of former Chilean Ambassador Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt in downtown Washington, D.C. It was this FBI report that resulted in the revelation of the existence of the Condor system in 1979, when its author, FBI attaché Robert Scherrer, testified at a trial of several Cuban exiles who assisted the Chilean secret police in assassinating Letelier and Moffitt.

- The first Senate investigative report on Condor based on CIA documents and briefings written in early 1979 by Michael Glennon, a staff member of the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on International Operations. The draft report was never officially published but was leaked to columnist Jack Anderson; a copy was eventually obtained by John Dinges and Saul Landau and used in their book, Assassination on Embassy Row. A declassified copy was released as part of the Obama-authorized Argentina Declassification Project in 2019.

“These documents record the dark history of multilateral repression and state-sponsored terrorism in the Southern Cone—a history that defined those violent regimes of the past,” notes Peter Kornbluh, author of The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability. “Fifty years after Condor’s inauguration, these documents provide factual evidence of coordinated human rights atrocities that can never be denied, whitewashed or justified.”

After many years of investigations and resulting trials, it is now clear that Condor may have backfired on its perpetrators, according to John Dinges, whose updated and expanded edition of The Condor Years was published in Spanish in 2021 as Los Años del Condor: Operaciones Internacionales de asesinato en el Cono Sur. “It is a kind of historic irony,” Dinges notes, “that the international crimes of the dictatorships spawned investigations, including one resulting in Pinochet’s arrest in London, that would eventually bring hundreds of the military perpetrators to justice. Moreover, because Condor’s most notorious crime was in Washington, D.C., the United States government unleashed the FBI to prosecute DINA and the Chilean regime.”

Other documents on Condor discovered in the archives of member states such as Uruguay can be found on this special website—https://plancondor.org/—established to record the history of Condor’s human rights atrocities and hold those who committed them accountable for their crimes.

Special thanks to Carlos Osorio whose years of work documenting Operation Condor made this posting possible.

The Documents

Document 1

Rettig Commission Files, as reproduced in The Pinochet File, by Peter Kornbluh

This summary of Operation Condor’s inaugural meeting, hosted by the Chilean secret police, DINA, in Santiago, Chile, provides substantive detail on the mission, coordination, communications, intelligence sharing, joint operations and the Latin American intelligence officers involved in initiating a regional effort to suppress the left in the Southern Cone. It also identifies the origins of the name of this cross-border collaboration - Chile’s national bird, the condor. “This organization will be called CONDOR, by unanimous approval of a motion presented by the Uruguayan Delegation to honor the host country,” the document concludes. In January 1976, this founding document was signed by five high-ranking intelligence officers in the Southern Cone, representing the original Condor nations: Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and Bolivia. Peru and Ecuador joined Condor in 1977. Brazil became a formal member in 1976; Peru and Ecuador joined Condor in 1978.

Document 2

Argentina Declassification Project

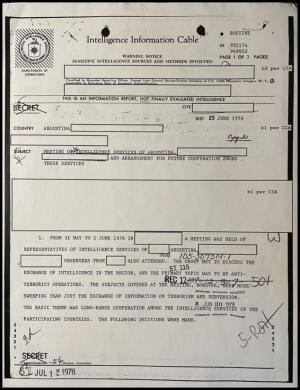

This CIA report summarizing the second meeting of Southern Cone intelligence services in Santiago, Chile, from May 31 to June 2, 1976, is the first known declassified document to reference “Condor.” The report states that “Condor, the name given to this cooperative arrangement, will establish a basic computerized data bank” to centralize intelligence registries on operations against leftist enemies. The CIA also reports that, besides intelligence sharing, Chile “agreed to operate covertly” with the Argentines and Uruguayans to conduct operations “against the Revolutionary Coordinating Junta (JCR) and other terrorists.” Those operations to assassinate targets abroad would expand Condor’s reach outside of the Southern Cone to Europe and elsewhere.

Document 3

Argentina Declassification Project

This CIA cable describes a third Condor meeting, held in Buenos Aires on July 2, 1976, that focused on “mounting of operations in France.” “The basic mission of the teams being sent to operate in France,” the cable states, “will be to liquidate top-level terrorist leaders.” The CIA also reveals divisions within the Condor states about these operations but notes that “the bulk of the effort in France will probably be carried out by Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay.” Brazil’s contribution, the document suggests, “will be to supply communications equipment for the Condor net in Latin America.”

Document 4

Argentina Declassification Project

This CIA report, drawn from the same source that provided information for the July 21, 1976, cable, is the first to provide details of Condor plans to “liquidate” targets in France. The report provides the first breakdown for the Condor bureaucratic “groupings,” including CONDORTEL for communications and CONDOREJE for operations. Not only leftists residing in Europe will be targeted, the source reports, but “some leaders of Amnesty International might be selected for the target list.” The document remains significantly redacted hiding considerable information about Condor’s planned operations.

Document 5

Argentina Declassification Project, April 2019

In this memo to the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, Raymond A. Warren, CIA Chief of the Latin America Division, raises concerns that the “Condor” countries are organizing assassination squads with the specific purpose “to liquidate key Latin American terrorist leaders” outside the Southern Cone region. This Condor program “poses new problems for the Agency,” he warns, and “every precaution must be taken to ensure that the Agency is not wrongfully accused of being party to this type of activity.” Warren asks his superiors “what action the Agency could effectively take to forestall illegal activity of this sort.”

Document 6

Department of State Argentina Declassification Project

In early August 1976, this 14-page briefing memo for Henry Kissinger alerts him to the existence of Operation Condor. Assistant Secretary of State for Latin America, Harry Shlaudeman, advises Kissinger that the Southern Cone governments see themselves as engaged in a Third World War against terrorism and that they “have established Operation Condor to find and kill terrorists … in their own countries and in Europe.” “[T]hey are joining forces to eradicate ‘subversion’, a word which increasingly translates into non-violent dissent from the left and center left.” Their definition of subversion is so broad as to include “nearly anyone who opposes government policy.” Shlaudeman echoes the concerns of CIA officials that Condor death squads will create serious repercussions for the United States. “Internationally, the Latin generals look like our guys,” Shlaudeman notes. “We are especially identified with Chile. It cannot do us any good.”

Document 7

Argentina Declassification Project

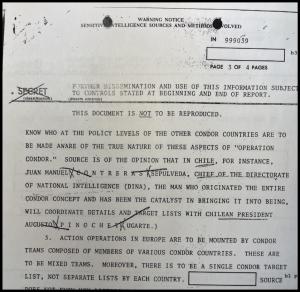

This CIA cable illuminates how Condor officials in Uruguay, Chile and the other member nations will secretly select targets “to liquidate” in Europe and who will know about these missions. The source of the CIA intelligence suggests that “in Chile, for instance, Juan Manuel Contreras Sepulveda, chief of the Directorate of National Intelligence (DINA) the man who originated the entire Condor concept and has been the catalyst in bringing it into being, will coordinate details and target lists with Chilean President Augusto Pinochet Ugarte.” The CIA reports that “action operations in Europe are to be mounted by Condor teams of various Condor countries. These are to be mixed teams. Moreover, there is to be a single Condor target list, not separate lists by each country.”

Document 8

Argentina Declassification Project, April 2019

This memo recounts a meeting between CIA and State Department officials—among them, Hewson Ryan, the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs, James Gardner, head of the Department of State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR), and the CIA’s deputy chief of the Latin America division. They discuss a draft of a diplomatic demarche to the Condor regimes most involved in international assassination planning—Chile, Argentina and Uruguay. The CIA signs off on the demarche.

Document 9

Argentina Declassification Project, April 2019

The CIA’s Chief of the Latin America Division, Raymond A. Warren, once again raises alarms about planned Condor operations in France. In this memo, he reports that the CIA is so concerned that such operations will have “repercussions” for the CIA’s own liaisons with the Western European intelligence services that the Agency has taken steps “to preempt any political ramifications for the Agency” by alerting French authorities to the Condor assassination missions. Warren also informs his superiors that the State Department has sent a special demarche to Chile, Argentina and Uruguay to pressure those regimes to curtail international assassination operations.

Document 10

Argentina Declassification Project, April 2019

The CIA obtained the “text of the agreement by Condor countries regulating their operations against subversive targets”—a comprehensive planning paper on financing, staffing, logistics, training and selection of targets that reveals both the banal and dramatic details about the organizing and implementing of Condor’s “Teseo” death squad operations. The “Teseo” operations base would be located “at Condor 1 (Argentina).” Each member country was expected to donate $10,000 to offset operational costs, and dues of $200 would be paid “prior to the 30th of each month” for maintenance expenses of the operations center. Expenses for agents on assassination missions abroad were estimated at $3,500 per person for ten days, “with an additional $1000 first time out for clothing allowance.” Condor’s “Teseo” death squad program was named for Theseus, the mythological Greek warrior-king who killed the half-man, half-bull Minotaur.

Document 11

Argentina Declassification Project, April 2019

The FBI’s legal attaché in Buenos Aires, Robert S. Scherrer, drafted this now famous “Chilbom” cable eight days after the car bomb assassination of former Chilean ambassador, Orlando Letelier, and his colleague, Ronni Karpen Moffitt, in Washington D.C. Scherrer’s sources pointed the finger of responsibility at General Augusto Pinochet and the Chilean secret police, DINA. This cable suggests the assassination may have been a “phase three” mission of Operation Condor. In 2019, this cable was declassified without any redactions, identifying Scherrer’s source as an official named Arturo Horacio Poire at Argentina’s presidential intelligence service, the Secretaria de Inteligencia del Estado (SIDE).

Document 12

Patricio Aylwin Presidential Archive at Alberto Hurtado University

In his only confession to the Pinochet regime’s infamous act of international terrorism made prior to being detained by the FBI in Chile, DINA hit man Michael Townley recounts how he received orders from DINA deputy director Pedro Espinoza to assassinate the leading opponent of the dictatorship, Orlando Letelier, in Washington D.C. “The explicit orders were: Find Letelier’s home and workplace and contact the Cuban group [of violent exiles working with DINA] to eliminate him, or use SARIN gas, or orchestrate an accident, or in the end by whatever method—but the government of Chile wanted Letelier dead.” In an important admission, Townley records that the mission would draw on the “Red Condor”—the Condor network of Southern Cone secret police services. His account details how he traveled to Paraguay to obtain false passports and visas to travel to the U.S., enlisted a team of Cuban-exile terrorists to assist him in the mission, and later assassinated Letelier and his young associate, Ronni Moffitt, who was riding in the car with her husband when the bomb was detonated.

Document 13

Argentina Declassification Project

Early public references of CIA knowledge of Operation Condor were provided by a Top Secret/Sensitive Senate staff report for the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on International Operations in mid-January 1979. The scandal of the Korean intelligence service, KCIA, operating in Washington, generated a Senate investigation into other foreign intelligence services also conducting surveillance, secret lobbying, disinformation and other operations in the United States. Since the Chilean secret police had already been identified as responsible for the car-bomb assassination of Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt, a Senate staffer named Michael Glennon obtained permission from the Carter White House to obtain CIA briefings based on secret intelligence records regarding DINA operations in the United States and around the world. Drawing on those detailed files shared with him at the CIA’s headquarters—many of which remain classified to this day—Glennon reported that “Chile has been the center of Operation Condor” and that DINA had stationed agents in Chilean embassies not only in the other Condor countries but also in Spain for operations in Western Europe. CIA briefers informed Glennon that they had learned Condor was “planning to open a station in Miami” but the CIA had alerted the State Department and voiced objections to its Condor liaisons and “the Condor Miami Station was never opened.”

Glennon had access to the memos of CIA Western Hemisphere chief Ray Warren on actions the Agency took to block Condor’s Teseo plots in Paris; the report cited efforts by the CIA to alert French and Portuguese authorities to Condor assassination missions in their countries. Glennon’s study also drew on a then-secret FBI report, written by FBI attaché Robert Scherrer one week after the assassination of Letelier and Moffitt, that provided extensive intelligence on “phase three” Condor death squad operations and suggested that it was “not beyond the realm of possibility that the recent assassination of Orlando Letelier in Washington D.C. may have been carried out as a third phase of Operation Condor.”

The Senate report was never officially published as a committee print. A draft was obtained by syndicated investigative columnist Jack Anderson, who published an eight-part series based on its contents. Although there were earlier references to the Condor alliance in Robert Scherrer’s testimony in the Letelier assassination trial in early 1979, Anderson’s August 2, 1979, Washington Post column titled “Condor: South American Assassins,” provided a more detailed description of Operation Condor in the U.S. media and established that the CIA had knowledge of the Condor plots even before the assassination of Letelier.

Document 14

State Department Argentina Declassification Project

In this unusual report, the Regional Security Officer, James Blystone, meets with a Battalion 601 Argentine intelligence source while a major Condor operation is unfolding in Peru. Peru joined Condor, along with Ecuador, in 1978; in June 1980, the Peruvian military government collaborated with Argentine operatives to kidnap and rendition four Montenero militants living in exile in Lima. Several of the targets were kidnapped in broad daylight in a public park, creating a major media spectacle. While the operation was unfolding, Blystone’s source tells him that, “The present situation is that the four Argentines will be held in Peru and then expelled to Bolivia where they will be expelled to Argentina. Once in Argentina they will be interrogated and then permanently disappeared.” The Lima rendition was one of the last recorded Condor operations.