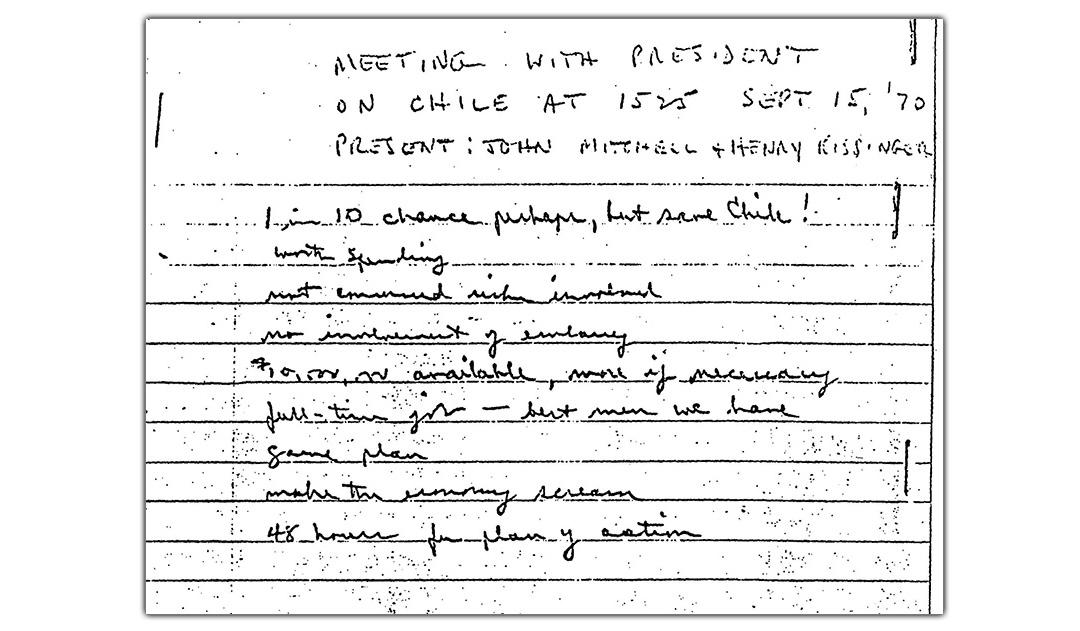

Washington, D.C., September 15, 2020 – On September 15, 1970, during a twenty-minute meeting in the Oval Office between 3:25 pm and 3:45 pm, President Richard Nixon ordered the CIA to foment a military coup in Chile. According to handwritten notes taken by CIA Director Richard Helms, Nixon issued explicit instructions to prevent the newly elected president of Chile, Salvador Allende, from being inaugurated in November—or to create conditions to overthrow him if he did assume the presidency. “1 in 10 chance, perhaps, but save Chile.” “Not concerned [about] risks involved,” Helms jotted in his notes as the President demanded regime change in the South American nation that had become the first in the world to freely elect a Socialist candidate. “Full time job—best men we have.” “Make the economy scream.”

Fifty years after it was written, Helm’s cryptic memorandum of conversation with Nixon remains the only known record of a U.S. president ordering the covert overthrow of a democratically elected leader abroad. Since the document was first declassified in 1975 as part of a major Senate investigation into CIA covert operations in Chile and elsewhere, Helms’s notes have become the iconic representation of U.S. intervention in Chile—and an enduring symbol of Washington’s hegemonic arrogance toward smaller nations.

To mark the 50th anniversary of Nixon's order to overthrow Allende, at precisely 3:25 pm – when the meeting began – the National Security Archive today posted a selection of previously declassified documents that traces the genesis of this consequential presidential directive and the historical circumstances in which it took place. The September 15, 1970, meeting, also attended by National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and Attorney General John Mitchell, is well known in the history of the U.S. role in Chile; the events that led to that meeting have received far less attention. “These documents provide a roadmap of U.S. coup-plotting and regime change,” notes Peter Kornbluh, who directs the Archive’s Chile project and is the author of The Pinochet File. “The September 15, 1970, Oval Office meeting marked the first major step in undermining Chilean democracy and supporting the advent of a military dictatorship."

photo credit, Naul Ojeda

The Archive’s abbreviated historiography of Nixon’s September 15 orders reveals the following sequence of events:

** U.S. officials began to secretly explore a military coup as part of contingency planning for a possible Allende victory more than a month before Chileans went to the polls on September 4, 1970. The initial evaluation of the pros and cons of a potential coup took place after President Nixon requested, in late July, an “urgent review” of U.S. interests and options in Chile. Completed in mid-August, the review known as National Security Study Memorandum 97, contained a TOP SECRET annex titled “Extreme Option: Overthrow Allende,” which addressed the assumptions, advantages, and disadvantages of a military coup if Allende was elected.

To prepare that section of the evaluation, on August 5, 1970, Assistant Secretary of State John Crimmins sent U.S. ambassador Edward Korry an “eyes only” cable seeking his views on “prospects for success of military and police who try and overthrow Allende or prevent his inauguration” and “the importance of U.S. attitude to initiate or success of such an operation.” Korry sent a 13-page response on August 11, 1970, which identified the key time frames, potential leaders for, and obstacles to, a successful military coup.

Four days after Allende’s narrow election, on September 8, 1970, the “40 Committee” which oversaw covert operations, met to discuss Chile. Henry Kissinger chaired the committee. At the end of the meeting, Kissinger requested a “cold blooded assessment” of “the pros and cons and problems and prospects involved should a Chilean military coup be organized now with U.S. assistance.” In response, Korry sent another detailed telegram titled “Ambassador’s Response to Request for Analysis of Military Option in Present Chilean Situation.” The Chilean military, he reported, “will not repeat not move to prevent Allende’s accession, barring unlikely situation of national chaos and widespread violence.” Opportunities for further U.S. action to push the military, Korry advised, “are nonexistent. They already know they have our blessing for any serious move against Allende.” The key player in any military move, Korry wrote, was not the United States but rather President Eduardo Frei on whose “will and skills” the future of Chile depended.

** In the initial aftermath of Allende’s election, coup plotting essentially was divided into two approaches:

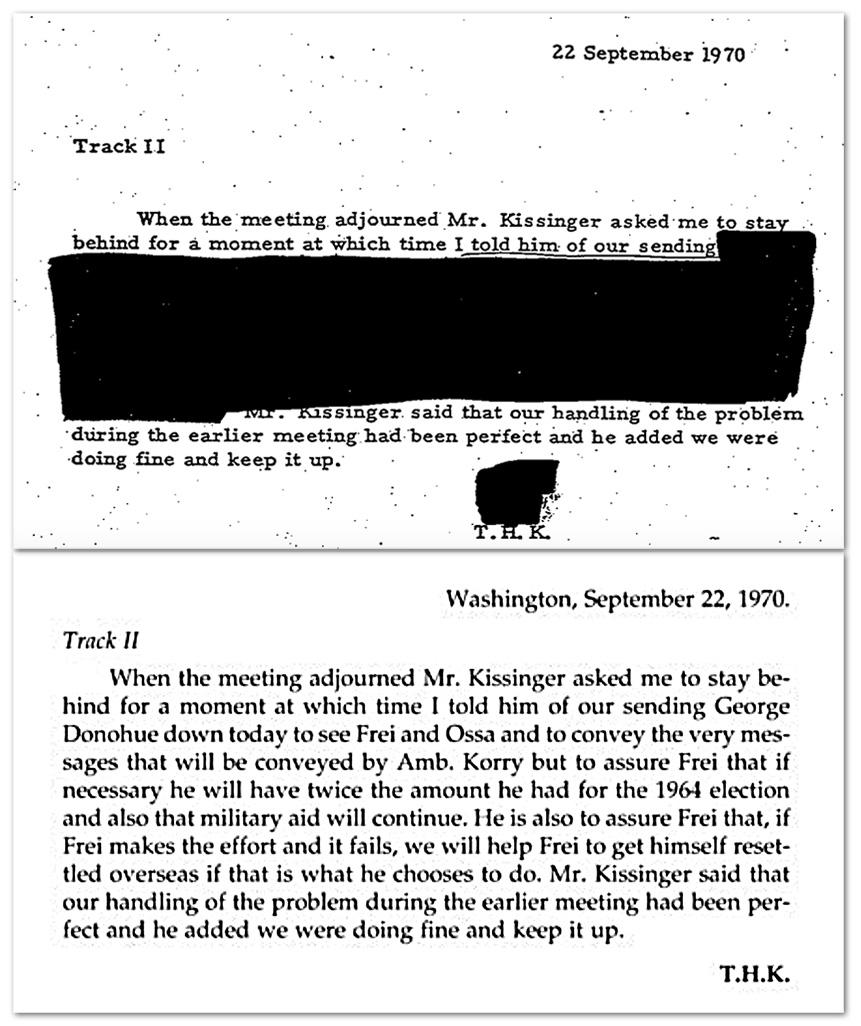

1) The “Frei formula” which counted on President Frei to “manage the coup” by authorizing senior military officers to move against the constitution. One early scheme called for Frei to annul the elections, name a military cabinet to run the government, appoint the runner-up Jorge Alessandri as an interim president, and resign with the expectation of running for president again in new elections. Through intermediaries and directly, U.S. officials pressed Frei to implement this complicated gambit and authorize the Chilean military to end what Korry called their “flabby irresolution.” The CIA even dispatched a special agent named George Donohue to Santiago to “assure Frei that if necessary he will have twice the amount [of CIA covert funding] he had for the 1964 election” if he orchestrated the plan and ran for re-election. If the plan failed, Donohue was instructed to tell Frei that the CIA would pay for him to resettle outside of Chile. Soon, however, the Embassy and the CIA concluded that Frei could not be counted on to betray his country.

2) The “chaos formula” for creating a “coup climate” to provide the Chilean military with the pretext for seizing power. Six days before Nixon ordered a military coup, William Broe, the head of the CIA’s Western Hemisphere division, instructed Santiago station chief Henry Hecksher to initiate “the operational task of establishing those direct contacts with the Chilean military which … could be used to stimulate a golpe if and when a decision were made to do so.” It had become apparent “in exploring avenues to prevent an Allende government from exercising power,” Broe noted, “that (A) the political/constitutional route in any form is a non-starter and (B) the only prospect with any chance of success whatsoever is a military golpe either before or immediately after Allende’s assumption of power.” Within days of Nixon’s September 15 directive, CIA headquarters began transmitting instructions for the “creation of coup climate” through “economic warfare,” “political warfare” and “psychological warfare.”

Redacted CIA memorandum of conversation on coup plotting, and unredacted text.

** The CIA station chief objected to these instructions as impractical and unlikely to succeed. He was not alone. A significant number of CIA, U.S. Embassy, and State Department officials opposed proposed plans for U.S. intervention as unrealistic, prone to failure, and diplomatically dangerous—with the risks of exposure far outweighing potential gains for U.S. interests. The State Department’s Latin America bureau formally opposed the secret annex in NSSM 97 on overthrowing Allende on the grounds that “exposure in an unsuccessful coup would involve cost that would be prohibitively high in our relations in Chile, in the hemisphere, and elsewhere in the world. Even were the coup successful, exposure would involve costs only marginally less serious in all these areas.” In a private cable to Kissinger, Ambassador Korry warned that “I am convinced we cannot provoke [a coup] and that we should not run the risks simply to have another Bay of Pigs.” Even Kissinger’s top aides on the NSC opposed intervening in Chile’s internal political affairs. On September 14, Winston Lord sent him a memo with the unique argument that, if exposed, U.S. intervention in Chile “could completely undercut our policy on Vietnam” which was predicated on free elections and “self-determination of the South Vietnamese people without foreign interference.” The same day, another Kissinger deputy at the NSC, Viron Vaky, warned him that U.S. intervention could lead to “widespread violence and even insurrection” in Chile.

Most courageously, Vaky questioned whether the threat of an Allende government really outweighed the dangers and risks of the chain of events U.S. intervention could set in motion. He advised Kissinger on the answer: "What we propose is patently a violation of our own principles and policy tenets .… If these principles have any meaning, we normally depart from them only to meet the gravest threat to us, e.g. to our survival. Is Allende a mortal threat to the U.S.? It is hard to argue this."

** Henry Kissinger rejected these arguments, and disparaged them in his briefings to the president. Kissinger, along with CIA Director Helms, fully supported overthrowing Allende at any cost. On September 12, they talked on the phone about a preemptive coup to block Allende—a conversation Kissinger recorded on his secret taping system. "We will not let Chile go down the drain," Kissinger declared. "I am with you," Helms responded.

** Of all the influencers on President Nixon’s September 15 coup directive, Kissinger was the strongest for three reasons: his position as national security advisor; his endorsement of Nixon’s deep distain for the State Department; and his own concern that Allende’s free and fair election would become a model for other nations in Latin America and Europe, threatening U.S. control and alliances. But Nixon was also influenced by reading Ambassador Korry’s detailed cables which emphasized the need for economic upheaval to create a justification for the coup and specified a window of opportunity for a coup before the Chilean Congress would ratify Allende on October 24.

The timing of Nixon’s decision corresponded to the presence in Washington of Agustin Edwards, the owner of Chile’s leading newspaper, and a leading CIA informant on the potential for a coup in Chile. On September 14, Edwards had breakfast with Kissinger and Attorney General John Mitchell; he then held a long meeting with Richard Helms and provided detailed intelligence on potential coup leaders in the military and political establishment in Chile. Kissinger sought to arrange a secret Oval Office meeting between Edwards and Nixon—so secret that no records exist to confirm it took place. Nixon did meet on September 14 with his close friend Donald Kendall, the CEO of Pepsi, with whom Edwards was staying, and Kendall briefed the president on Edwards arguments. Helms would later testify that “the President called this [September 15] meeting because of Edwards’ presence in Washington and what he heard from Kendall about what Edwards was saying about conditions in Chile.”

In reality, Nixon needed little persuasion. He appeared to take Allende’s election as a deliberate affront to the United States. “All over the world it’s too much the fashion to kick us around,” Nixon would later tell his top national security officials as they determined a long-term policy to undermine Allende’s government. “We cannot fail to show our displeasure.”

** ** **

Richard Nixon’s directive to Helm’s 50 years ago set in motion a series of some of the more infamous acts in the annals of U.S. foreign policy. To instigate a coup, the CIA soon focused on providing guns, funds, and even life insurance policies for Chilean military operatives to remove the commander-in-chief of the Chilean armed forces, General Rene Schneider, who opposed a golpe. On October 22, 1970, Schneider was intercepted and shot on his way to work; he died three days later. His CIA-supported murder became one of the most legendary cases of U.S. involvement in the assassination of foreign leaders. The CIA’s short-term covert effort to block Allende’s inauguration evolved into a protracted three-year clandestine effort to destabilize his ability to govern, creating the “coup climate” that led directly to the September 11, 1973, military takeover led by General Augusto Pinochet. A year later when reporter Seymour Hersh broke the story of U.S. intervention in Chile on the front page of the New York Times, the exposure that Kissinger’s aides feared created one of the biggest foreign policy scandals in recent U.S. history.

“Carnage will be considerable and prolonged,” a TOP SECRET CIA cable from the Santiago station predicted as agents began to actively implement Nixon’s orders. “You have asked us to provoke chaos in Chile …. we provide you with formula for chaos that is unlikely to be bloodless. To dissimulate U.S. involvement will clearly be impossible.”

READ THE DOCUMENTS

Document 1

National Security Archive Chile Collection

In response to President Nixon’s request for a review to prepare contingency plans in the event of an Allende victory in Chile, the CIA, State Department and Defense Department prepare a broad study, with this secret annex on an “extreme option” to overthrow Allende. The drafters caution that revelations of a U.S. role in overthrowing Allende could have “grave consequences for U.S. interests in Chile, the hemisphere and around the world.”

Document 2

Clinton Administration Chile Declassification Project

Responding to a request to evaluate a TOP SECRET option for a coup against Allende if he is elected, the U.S. ambassador to Chile sends a lengthy cable predicting that it is “highly unlikely that the conditions or motivations for a military overthrow of Allende will prevail.”

Document 3

Clinton Administration Chile Declassification Project

In a memorandum to Undersecretary of State U. Alexis Johnson, the head of the Bureau of Latin America Affairs (ARA), Charles Meyer, requests that the State Department oppose covert efforts to implement the “extreme option” of overthrowing Allende on the grounds that the likelihood of success is low and the risks of exposure are high.

Document 4

Clinton Administration Chile Declassification Project

Four days after Allende’s election, Henry Kissinger chairs the first meeting of the 40 Committee, which overseas covert operations abroad. At the end of the meeting, Kissinger requests that the Embassy immediately provide a “cold blooded assessment” of the pros and cons of a military coup to keep Allende from being inaugurated president.

Document 5

Clinton Administration Chile Declassification Project

The CIA’s head of Western Hemisphere operations, William Broe, transmits a cable to the CIA station chief in Santiago with instructions to establish contacts with Chilean military officers in preparation for providing support for a military coup against Allende.

Document 6

Clinton Administration Chile Declassification Project

Ambassador Korry responds to Kissinger’s request for a “cold blooded” assessment of a potential for a coup by stating forcefully that the Chilean military will not move unless there is “national chaos and widespread violence.”

Document 7

National Security Archive Kissinger Telcon collection

In a phone conversation, Kissinger and Helms discuss the situation. Kissinger makes it clear that he and President Nixon are unwilling to let Chile “go down the drain.” “I am with you,” Helms replies.

Document 8

Clinton Administration Declassification Project

In a memorandum to prepare Henry Kissinger for a 40 Committee meeting on Chile, his top deputy for Latin America, Viron Vaky, takes the opportunity to warn against U.S. efforts to block Allende. In addition to the costs of possible exposure to the reputation of the United States abroad, he advances a bold moral argument: “What we propose is patently a violation of our own principles and policy tenets.”

Document 9

Senate Select Committee to Study Government Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, Covert Action in Chile, 1963-1973.

In these handwritten notes, CIA Director Richard Helms records the instructions of President Richard Nixon to foment a coup in Chile. The president gives him 48 hours to develop a plan, authorizes a minimum budget of $10 million dollars, and instructs him not to tell U.S. Embassy officials that the CIA is plotting Allende’s overthrow.