Washington, D.C., December 6, 2021 — This week, as NATO concludes its annual flagship cyber exercise, Cyber Coalition 21, newly declassified documents detail American collaboration with NATO allies to dissuade and impede Russian advances, both in cyberspace and in European territory. The recently released materials feature after action reports (AARs) and planning documents concerning the BALTIC GHOST series of cyber exercises. When combined with other sources, they record BALTIC GHOST’s evolution from a partnership-building exercise between Estonian forces and U.S. National Guard units, to a multi-day, multi-nation series of workshops and table-top activities that directly support the U.S. European Command in its mission to deter Russia and support NATO. The National Security Archive obtained the records from USEUCOM under the Freedom of Information Act.

* * * * *

BALTIC GHOST: Supporting NATO in Cyberspace

By Cristin J. Monahan

The BALTIC GHOST series of exercises originated in 2013 as a group of “cyber defense workshops facilitated by U.S. European Command (USEUCOM) to build and sustain cyber partnerships amongst Estonia and the Maryland ARNG [Army National Guard], Latvia and the Michigan ARNG, and Lithuania and the Pennsylvania ARNG” (Document 1, p. 39). Jeffrey L. Caton, a former faculty member at the United States Army War College, notes in Examining the Roles of Army Reserve Component Forces in Military Cyberspace Operations, “With the increased concern for Russian military cyberspace activity, the SPP [Army National Guard State Partnership Program] programs with the Baltic nations have grown in prominence” (p. 38).

Such pointed concerns likely originate from the 2007 two-week cyber attack on Estonian infrastructure, an onslaught determined to be of Russian origin. The attack followed the Estonian government’s decision to move a World War II-era statue from the center of Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, to a military cemetery on Tallinn’s perimeter. The Bronze Solder was originally erected to commemorate the USSR’s victory over Nazism and as a dedication to the fallen members of the Soviet Red Army, but in the decades to follow, became a symbol of Soviet occupation and oppression for ethnic Estonians. The April 2007 announcement of the monument’s relocation created a political row between Estonia and Russia, and Tallinn erupted into two nights of riots as Russian speakers occupied the streets. Shortly thereafter, Estonian banks, media outlets, and other infrastructure were brought to a crawl by a coordinated cyber-attack originating from Russian IP addresses.

NATO in Cyberspace

While the attacks crippled Estonia in the short term, they also produced significant long-term effects. The assault on Estonia demonstrated Russia’s ability and willingness to use its cyber capabilities to achieve political goals, and catapulted Estonia into the international spotlight for national cyber defense development. On a geopolitical level, however, the attacks showed how easily NATO allies could be entangled in a cyber conflict, should its effects be commensurate with a traditional military action.

Such realities led the Heads of State and Government of the North Atlantic Council (the primary political decision-making body within NATO), convened in 2014 at the Wales Summit, to “affirm that cyber defence is a part of NATO’s core task of collective defence” (Document 2). The Wales Summit Declaration concludes that cyber threats will continue to increase in frequency, sophistication and potential lethality, and as such, the assembled members endorsed an enhanced Cyber Defence Policy, “contributing to the fulfilment of the Alliance’s core tasks.” It cautions, however, that while cyber attacks can be as harmful to nations as conventional attacks, the “decision as to when a cyber attack would lead to the invocation of Article 5 would be taken by the North Atlantic Council on a case-by-case basis” (Document 2, para. 72). The Declaration affirms that “the fundamental cyber defence responsibility of NATO is to defend its own networks, and that assistance to Allies should be addressed in accordance with the spirit of solidarity, emphasizing the responsibility of Allies to develop the relevant capabilities for the protection of national networks.”

Transition

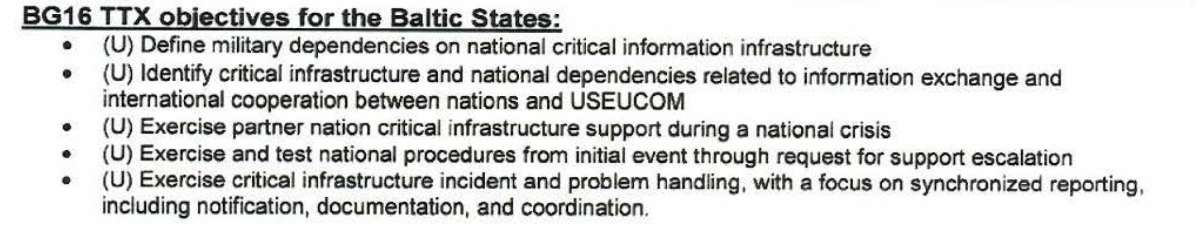

Perhaps in light of the findings of the Wales Summit, BALTIC GHOST “transitioned to become a training exercise in September 2015―held simultaneously in the capitals of Tallinn (Estonia), Riga (Latvia), and Vilnius (Lithuania)―and focused on the coordination of responses to cyberattacks on critical infrastructure” (Document 1, p. 40). The first primary document that speaks to this transition is a US European Command after action report (AAR) for the 2016 BALTIC GHOST Table Top Exercise (TTX) (Document 3). The 2016 AAR establishes exercise objectives for the Baltic States, but does not mention USEUCOM’s own objectives, suggesting that the command’s primary role was as exercise facilitator.

While most of the report’s “Discussion Points” and “USEUCOM Takeaways” are redacted, the report notes that participants “utilized the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Center of Excellence (CCDCOE) online exercise facilitation capability to input exercise scenarios.” The platform provided the “global synchronization, reporting and documentation” capabilities that would be critical not only in a notional scenario, but in the actual event of a cyber attack that justified invoking Article 5.

NATO’s “Cyber Defence Pledge”

As the planning of BALTIC GHOST 2016 entered its final stages, NATO’s Heads of State and Government gathered at the Warsaw Summit and developed the Cyber Defence Pledge (Document 4) “to ensure the Alliance keeps pace with the fast evolving cyber threat landscape and that our nations will be capable of defending themselves in cyberspace as in the air, on land and at sea.” The pledge reaffirms each member’s national responsibility to secure and defend its own networks and infrastructure, but also emphasizes “NATO’s role in facilitating co-operation on cyber defence including through multinational projects, education, training, and exercises and information exchange, in support of national cyber defence efforts.” In addition to a commitment from member states to adequately resource their respective cyber defense capabilities and to promote cyber education and awareness, the members pledge to “develop the fullest range of capabilities to defend our national infrastructure and networks,” including “addressing cyber defence at the highest strategic level within our defence related organizations, further integrating cyber defence into operations and extending coverage to deployable networks.” Tellingly, the pledge also opens the door to enhanced cyber exercises between NATO nations, as members also commit to “reinforce the interaction amongst our respective national cyber defence stakeholders to deepen co-operation and the exchange of best practices,” as well as to “foster cyber education, training and exercising of our forces … to build trust and knowledge across the Alliance.”

BALTIC GHOST 2017

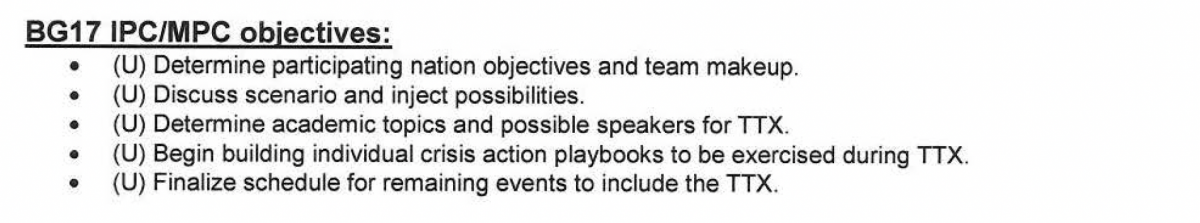

The 2017 exercise represents the first in the BALTIC GHOST series planned entirely after the release of NATO’s Cyber Defence Pledge. The planning documents for BALTIC GHOST 2017 provide insight into the participants and their individual interests, the structure of the exercise and the U.S. forces’ involvement in the BALTIC GHOST series. In the after action report for the BALTIC GHOST 2017 Initial Planning Conference/Mid-Term Planning Conference (IPC/MPC) (Document 5), BALTIC GHOST is described as “USEUCOM-supported series of workshops culminating in a Cyber Defense Table Top Exercise (TTX) between Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. US DOD participation includes USEUCOM, DISA [Defense Information Systems Agency], USCYBERCOM, and National Guard Units from Maryland, Michigan, and Pennsylvania participating as part of the National Guard State Partnership Program (SPP).” The report identifies the presence of exercise observers, namely Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and the United Kingdom. It also highlights USEUCOM’s equities in the exercise, namely that “Baltic Ghost (BG) directly supports two USEUCOM lines of effort: Deter Russia and Support NATO.”

Document 5’s “Objectives” and “Discussion Points” sections demonstrate the ongoing dialogues among participants, specifically around the development of exercise scenarios and playbooks, as well as academic speakers and topics for presentation. While the report states broadly that the exercise will “focus on crisis action collaboration mechanisms between military, national and commercial cybersecurity organizations,” one of the Discussion Points asserts, “the BG17 scenario will focus on the civilian/military energy sector, with a focus on those impacting military bases.” The decision to incorporate the energy sector into the exercise scenario is unsurprising, given repeated cyber attacks, determined to be of Russian origin, on Ukraine’s power grid in 2015 and 2016. The Discussion Points section also reveals Estonia’s desire to include air defense issues into the exercise, while Lithuania “would like to include critical transportation sectors which might affect troop or equipment movement.”

Document 6, the AAR for the Final Planning Conference of BG17, confirms that the concerns of Lithuania and Estonia were incorporated into the final exercise scenario. The second Discussion Point of Document 6 describes the final BG17 scenario as focusing on “the Baltic nations’ civilian/military energy [emphasis added] and logistics sector, with a focus on on those impacting U.S. military forces which might affect troop or equipment movement.” Furthermore, as part of the planned scenario, “Estonia will include injects covering the Maryland National Guard A10 [Thunderbolt II fighter] unit on rotation in Estonia,” thus addressing that nation’s concerns over air defense.

Unfortunately, the after action report for the BALTIC GHOST 2017 Table Top Exercise (Document 7) reveals very little about the information gleaned from the actual exercise, as the “Lessons Learned” and “USEUCOM Takeaways” sections released under FOIA are redacted in their entirety. However, Document 7 states that one of the two exercise objectives is to “develop and exercise communication channels for the sharing of critical information and the development of TTPs enabling requests for support for cyber mission forces from Baltic States.” Such communication and information sharing processes would be vital in the event of an invocation of Article 5 due to a cyber attack.

BALTIC GHOST 2018 and the Brussels Summit

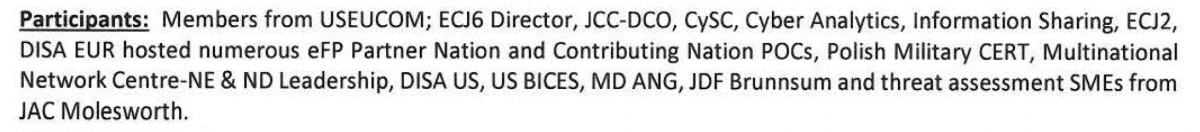

Document 8, the after action report for a USEUCOM-presented seminar, ‘eFP Cyber Defense’ is the only document that speaks to BALTIC GHOST 2018’s slate of events. The report notes that USEUCOM’s Joint Cyber Center (JCC) Defensive Cyber Operations and Cyberspace Security Cooperation (DCO/CySC) branches concluded a seminar on enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) Cyber Defense. The event “welcomed nearly 50 attendees from 9 partner nations and SMEs [subject matter experts] from diverse support agencies.”

While more than half of Document 8 is redacted, the two available Discussion Points, as well as the participant list displayed above, demonstrate how BALTIC GHOST 2018 was employed to fulfill elements of the 2016 Cyber Defence Pledge. Some of the key topics discussed in the seminar include “multinational cyberspace information sharing, operational integration of cyber defense, and synchronization across the information domain.” Additionally, as part of the seminar, “participants identified existing national cyber capabilities and opportunities for better coordination and communication.”

Shortly after the conclusion of BALTIC GHOST 2018, the Heads of State and Government released the Brussels 2018 Summit Declaration (Document 9), which affirms NATO’s commitment to “employ the full range of capabilities, including cyber, to deter, defend against, and to counter the full spectrum of cyber threats, including those conducted as part of a hybrid campaign” (Document 9, para. 20). Document 9 also clarifies the ability of individual nations to attribute malicious cyber activity to specific actors, and to respond “in a coordinated manner, recognizing attribution as a sovereign national prerogative.” Additionally, the 2018 declaration emphasizes the value of Alliance information sharing and synchronization, as discussed and cultivated in the previous BALTIC GHOST exercises: “We have agreed how to integrate sovereign cyber effects, provided voluntarily by Allies, into Alliance operations and missions, in the framework of strong political oversight.”

BALTIC GHOST 2019

The after action documents from BALTIC GHOST 2019 provide perhaps the most insight into the role of the exercise series in the evolution of the Alliance’s strategy of cyber defense, particularly as a means to support military operations. NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) is featured prominently in BG19, and refers to NATO’s increased military presence in the eastern portion of the Alliance, comprised of four battlegroups in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. A NATO-issued factsheet on eFP (Document 10) asserts that “these battlegroups, led by the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany and the United States respectively, are multinational, and combat-ready, demonstrating the strength of the transatlantic bond. Their presence makes clear that an attack on one Ally will be considered an attack on the whole Alliance” (p.1).”

The AAR for Exercise BALTIC GHOST 2019 (Document 11) describes the exercise as directly supporting eFP, and reports that participants, which included Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, the United Kingdom, and various U.S. forces and agencies, “were asked to explore the operations, actions, and activities in the cyber domain necessary to respond to aggression in a cyberspace contested, degraded and denied environment” (p.1).

While the details of the exercise scenario are redacted, the scenario objectives are available:

The report highlights that a common discussion topic from BG19, as well as previous exercises, included information sharing challenges, specifically “nation to nation trust and authorities, technical availability, and a general understanding of what can be shared” (p.1). These concerns are echoed by the introductory brief shared by the U.S.-led eFP battlegroup in Poland, which emphasized the critical importance of “confidentiality, integrity, and availability of IT systems, noting that without availability users will often disregard integrity and confidentiality” (p.3). The Summary concludes that the findings and outcome of BG19 queued “increased discussions at the National and Coalition level to address identified gaps and challenges” (p.1).

The final document from BG19 is the AAR for U.S./Poland Key Leader Engagement (Document 12), referring specifically to a visit by USEUCOM’s J6, Brig. General Maria Biank, and the director of the Polish National Cyber Security Center (NCSC). While little is noted about the content of the visit or leadership’s interactions with exercise participants, the report notes that directly after the visit, BG Biank and the Polish NCSC director “participated in an official ceremony to sign the Cyberspace Cooperation Agreement,” signifying “the final approval to begin cooperation [between the two nations] in cyberspace.”

The Documents

Document 1

United States Army War College, https://publications.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/3674.pdf.

This piece, published by the US Army War College and the Strategic Studies Institute, examines the evolving roles of Army Reserve component forces, including the National Guard, in cyber space operations and exercises, including exercise series BALTIC GHOST.

Document 2

NATO, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_112964.htm.

This statement from the North Atlantic Council’s Heads of State and Government “affirm[s] that cyber defence is a part of NATO’s core task of collective defence,” but cautions that the “decision as to when a cyber attack would lead to the invocation of Article 5 would be taken by the North Atlantic Council on a case-by-case basis.”

Document 3

Freedom of Information Act Request

This USEUCOM after action report for exercise BALTIC GHOST 2016 provides exercise objectives for the Baltic States, but not U.S. forces, suggesting USEUCOM’s primary role was exercise facilitator.

Document 4

NATO, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133177.htm.

The "Cyber Defence Pledge," developed at the 2016 Warsaw Summit, affirms “NATO’s role in facilitating co-operation on cyber defence including through multinational projects, education, training, and exercises and information exchange, in support of national cyber defence efforts.”

Document 5

Freedom of Information Act Request

This USEUCOM after action report for the BALTIC GHOST 2017 Initial Planning Conference/Mid-Term Planning Conference (IPC/MPC) highlights that USEUCOM’s participation in the exercise supports two lines of effort: Deter Russia and Support NATO.

Document 6

Freedom of Information Act Request

The after action report for the Final Planning Conference of BALTIC GHOST 2017 demonstrates the integration of nation participants’ equities and interests in the final formulation of the exercise.

Document 7

Freedom of Information Act Request

This largely redacted after action report from USEUCOM reveals that one of the primary exercise objectives from BALTIC GHOST 2017 was “To develop and exercise communication channels for the sharing of critical information and the development of TTPs enabling requests for support for cyber mission forces from Baltic States.”

Document 8

Freedom of Information Act Request

This USEUCOM after action report for a USEUCOM-presented seminar, ‘eFP Cyber Defense,' as part of the slate of BALTIC GHOST 2018 events, reveals how some of the key topics discussed support the 2016 "Cyber Defence Pledge," including “multinational cyberspace information sharing, operational integration of cyber defense, and synchronization across the information domain.”

Document 9

NATO, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_156624.htm.

Released shortly after the conclusion of BALTIC GHOST 2018, this declaration by the North Atlantic Council’s Heads of State and Government confirms that the Alliance will “employ the full range of capabilities, including cyber, to deter, defend against, and to counter the full spectrum of cyber threats, including those conducted as part of a hybrid campaign.”

Document 10

NATO, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2020/10/pdf/2010-factsheet_efp_en.pdf.

This NATO factsheet describes the configuration of NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence (eFP), referring to NATO’s increased military presence in the eastern portion of the Alliance, comprised of four battlegroups in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. It asserts “these battlegroups, led by the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany and the United States respectively, are multinational, and combat-ready, demonstrating the strength of the transatlantic bond. Their presence makes clear that an attack on one Ally will be considered an attack on the whole Alliance.”

Document 11

Freedom of Information Act Request

This three-page USEUCOM after action report for BALTIC GHOST 2019 provides a summary of the exercise, a list of its participants, the exercise scenario objectives and analysis of information sharing challenges encountered during the exercise.

Document 12

Freedom of Information Act Request

This USEUCOM after action report for BALTIC GHOST 2019 - Key Leader Engagement refers to a visit to the ongoing exercise by USEUCOM’s J6, Brig. General Maria Biank, and the director of the Polish National Cyber Security Center (NCSC). The report also notes that after the visit the two leaders “participated in an official ceremony to sign the Cyberspace Cooperation Agreement,” signifying “the final approval to begin cooperation [between the two nations] in cyberspace.”