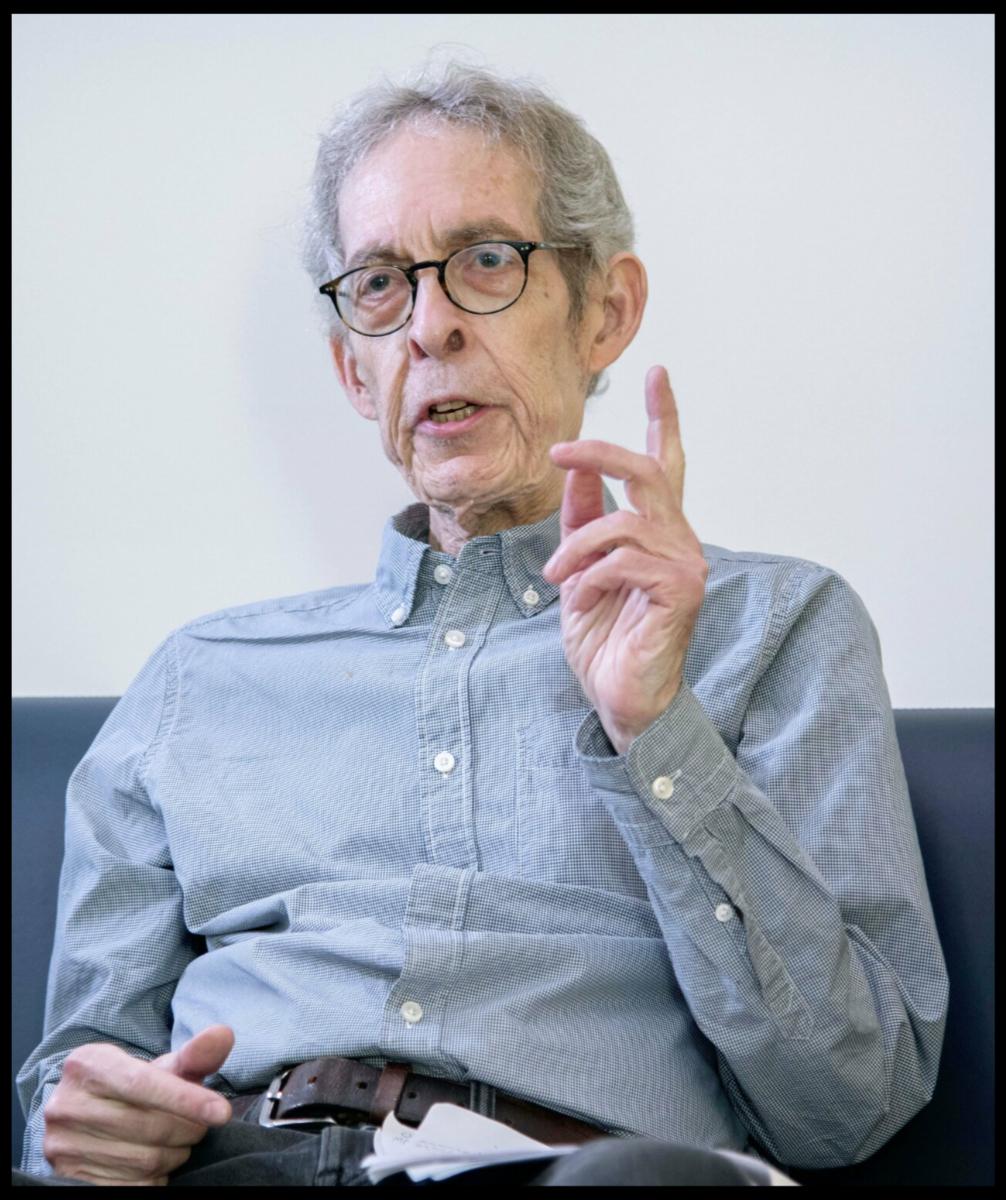

Washington, D.C., December 15, 2025 - The National Security Archive mourns the passing of our beloved colleague William Burr, the documentary leader of the nuclear history field, on December 11, 2025.

Tributes to Bill have poured in over the weekend from all over the world, emphasizing his brilliance as a scholar, his generosity as an archivist, his modesty and integrity as a person, his centrality to the whole field of nuclear studies, and the enormous legacies he leaves to the rest of us.

For the National Security Archive, Bill was the architect and hands-on builder of the Nuclear Vault, the online repository of essential primary sources on nuclear weapons and policies. Best-selling author Eric Schlosser described the Nuclear Vault as “a national treasure,” and the writer Ron Rosenbaum pronounced Bill “the Yoda of nuclear history.” Slate columnist Fred Kaplan wrote that Bill had pried more documents out of an unwilling bureaucracy than anybody else.

Bill compiled and edited some 233 Electronic Briefing Books of declassified documents over the years, including the Archive's very first such package in 1996. Bill also curated nine massive reference collections of primary sources on nuclear crises, Henry Kissinger’s diplomacy, nuclear history and nuclear non-proliferation for the award-winning Digital National Security Archive series published by ProQuest.

Earlier this year, the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations recognized Bill with the Anna Nelson Award for Archival Excellence, citing his lifetime of contributions to diplomatic history, his “exemplary expertise with government documents pertaining to U.S. foreign relations and international affairs” and his “outstanding and dedicated service to the scholarly community.”

Two decades earlier, the National Academy of Television Arts & Letters recognized Bill with the 2005 Emmy Award for “outstanding individual achievement in news and documentary research.” Bill’s excavations from both American and Chinese sources formed the basis for the breakthrough documentary film, “Declassified: Nixon in China,” and put Chinese agency back into the center of the story.

Bill Burr came to the National Security Archive in August 1988, a year after finishing his Ph.D. at Northern Illinois University. Previously he had worked at the Congressional Research Service and in several adjunct teaching positions. One notable project that showed the breadth of his expertise was to conduct an invaluable series of oral history interviews for Columbia University with State Department and CIA officials who had played pivotal roles in the U.S. relationship with the Shah of Iran, assuring that their stories—unavailable anywhere else—would become part of the permanent historical record. At first, not recognizing his superpower, the Archive put him in charge of the Freedom of Information database, tracking all the ins and outs of the Archive’s access requests. But soon, Bill’s extraordinary spelunking abilities led to his being put in charge of his own documentation projects, first covering the Berlin Crises of 1958-1962, and then into the entire field of nuclear history, which he quickly took over from a documentary point of view.

One of Bill’s many great legacies is the recovery of the Kissinger files. Henry Kissinger stole his office papers, the only complete set of his memcons and telcons, when he left office in 1976 after eight years under Nixon and Ford as national security advisor and Secretary of State. Kissinger first stashed the files at the Rockefeller estate at Pocantico, then made a deal with the Library of Congress to put the files there—in the guise of a gift but under Henry’s control until five years after his death. That would be 2029.

But various Kissinger aides had their own copies of meeting transcripts they had written up. Particularly important were the retired files of Winston Lord, the junior notetaker at the first Nixon-Mao meeting, who was redacted from the photographs so that then Secretary of State William Rogers wouldn’t be apoplectic on being left out. Combining the Lord documents on the China meetings with those of other aides who were with Kissinger in Moscow talks, Bill put together a great book, The Kissinger Transcripts, full of verbatim conversations so the reader is like a fly on the wall. The book announcement in 1998 drew a hostile letter from Kissinger’s lawyers at Cravath Swaine & Moore, threatening our publisher The New Press and the other distributor of the book—somebody named Bezos at a thing called Amazon—if we repeated our language about Kissinger’s having taken the main files.

That letter really got the Archive’s attention, plus our publisher was worried. Bill’s reaction was characteristic: he went downstairs to the stacks in Gelman Library and looked up all the court cases over Kissinger’s records. When journalists found out in the 1970s that Kissinger had secretly taped his phone calls (not only with the press, but also with his bosses Nixon and Ford!), the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press brought a lawsuit to open the telcons. They lost, and Kissinger seemingly got away with the purloined records.

But Bill saw in the Supreme Court decision what the Cravath lawyers had apparently missed. The Court never said the documents were Kissinger’s personal property, as he had claimed for decades, but rather, that the reporters just didn't have standing. In a concurrence, Justice Stevens even commented that the placement at the Library of Congress seemed designed to avoid the Freedom of Information Act, since Congress exempted itself from that law.

It took the Archive two more years and some great lawyering by our own Kate Martin and the pro bono firm of Mayer Brown (Lee Rubin, Craig Isenberg), but the threat of litigation persuaded the State Department that they had abdicated their duties under the records laws and had to recover the records. Thousands of Kissinger memcons and over 15,000 of his telcons are now on the public record, published in DNSA. All because of Bill Burr. A permanent scholarly tribute. A permanent accountability tribute.

Up until his last few weeks, Bill rode his bicycle to work and could always be found either standing over a hot scanner-copier with his latest document finds or in the Archive reading room mentoring a young intern or outside researcher. Bill’s generosity and helpfulness knew no bounds.

The Archive extends our profound condolences to Bill’s partner of 40 years, Ming-ju Sun, to Bill’s brother Chris Burr, sister Phyllis Orr, and all the members of Bill’s family. Bill’s memory is a blessing.

DNSA collections prepared by Bill

Set | Documents | Pages |

2,496 | 11,674 | |

2,163 | 28,461 | |

15,502 | 32,011 | |

639 | 3,986 | |

980 | 2,068 | |

2,301 | 12,645 | |

1,485 | 8,729 | |

1,441 | 20,474 | |

2,291 | 30,837 | |

| 29,298 | 150,885 |