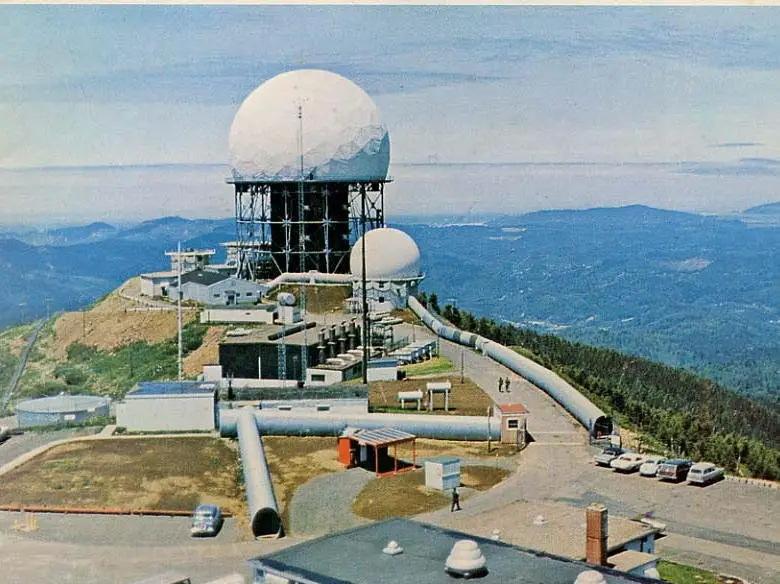

The U.S. Air Force’s missile warning station at Mount Hebo, Oregon, in its heyday, as depicted in an illustration published by the Tillamook Headlight Herald. On 3 October 1979, the radar, operated by Detachment 2 of the 14th Missile Warning Squadron, registered an incoming space object as a submarine-launched ballistic missile, leading to the convening of a Threat Assessment Conference. (Illustration used with permission from the publisher).

New Information on False Missile Alerts and Threat Assessment Conference Calls, 1977-1980

First publication of 1976 U.S-Soviet Agreement on NUCFLASH Messaging