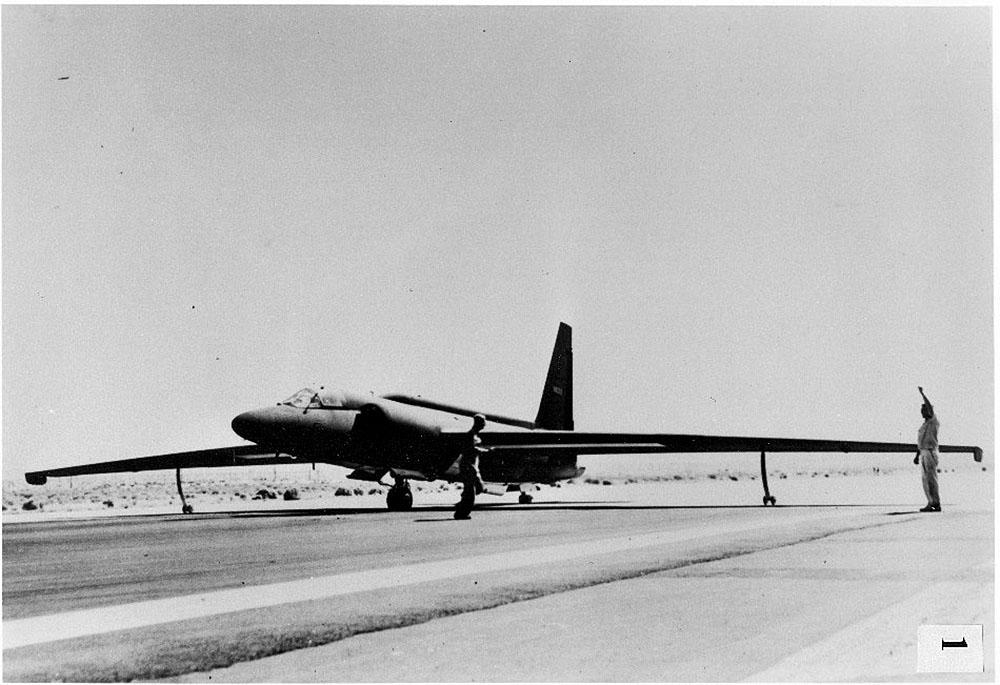

An early U-2 at the testing and training center, Groom Lake, Nevada. (Photo: Central Intelligence Agency)

Over 250 missions in late 1950s did more than take photos:

Secondary purpose was to acquire electronic and communications intelligence on the Soviet target

Document releases begin to flesh out still-highly classified U-2 SIGINT program